A ‘big data’ firm sells Cambridge Analytica’s methods to global politicians, documents show

Cambridge Analytica, the most notorious practitioner of psychological profiling, has closed shop. Their methods aren’t about to die out so easily.

Cambridge Analytica, the most notorious practitioner of psychological profiling, has closed shop. Their methods aren’t about to die out so easily.

A pitch deck from IDEIA Big Data, an international political research and marketing company, closely mirrors Cambridge Analytica’s tactics, to the extent that several sentences are copied from a 2016 Cambridge Analytica presentation. “If ‘IDEIA’ wasn’t on the pitch deck, you would think it’s a Cambridge Analytica presentation,” said Gary Wright, researcher for Tactical Tech, a nonprofit that investigates technology’s impact on society.

In 2018, Cambridge Analytica was exposed for collecting 87 million people’s data without their permission via Facebook. The company was condemned for using the harvested data to map and manipulate voters’ personality traits. There is no evidence from IDEIA’s May 2019 pitch deck that the company collects Facebook data in the same manner. But IDEIA—which claims to work with international political parties, including groups in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and Bolivia, as well as the United States Democrats—promotes psychological profiling tactics that are indistinguishable from Cambridge Analytica.

IDEIA’s methods of showing political content to particular groups (a practice known as “targeting”) raise civil liberty concerns, said Jeffrey Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy. “This document should sound global alarm bells that there are growing threats to the integrity of our elections as political campaigns weaponize personal data to manipulate how and whether we vote at all,” he added. “This is 1984 meets the 21st century.”

If IDEIA uses certain methods in the European Union (the company did not respond to questions about what tactics it has carried out where), a European court would question IDEIA’s work under the EU’s May 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), said Camille Gaffiot, a data protection lawyer at Fidal in France. In addition, the pitch deck references methods of collecting social media data and sending out messages that may violate the terms of certain social media platforms.

Below are pitch deck slides, created to attract clients, that show IDEIA mirroring Cambridge Analytica—including using their exact language—and indications of questionable methods. You can see the full pitch deck here.

IDEIA Big Data and Cambridge Analytica: Spot the difference

IDEIA uses the OCEAN model to determine personality type, which is the most rigorous psychological method of evaluating personality to date—and the model used by Cambridge Analytica. OCEAN is an acronym for the five traits it evaluates: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. (IDEIA opted for “need for stability” as a less negative descriptor of the fifth factor.)

Several sentences in the slides are exact transcriptions of a presentation Cambridge Analytica chief executive officer Alexander Nix gave in 2016. Though Nix’s presentation was well received at the time, once Cambridge Analytica was exposed, his speech was widely seen as sinister portrayal of the company’s attempts to manipulate the public.

Two minutes and thirteen seconds into his presentation, Nix makes several statements that appear in an IDEIA slide.

Less than a minute later, Nix introduces the OCEAN model that appeared on IDEIA’s deck. He explains each of the five personality traits, using descriptions that do not reflect standardized, scientific language. Nix’s characterizations of “conscientiousness” and “agreeableness” are particularly distinctive. For all five traits, IDEIA uses Nix’s words in its pitch deck.

Wright, who recognized IDEIA’s pitch deck language from Nix’s presentation, said the slides are “a near verbatim copy” of Cambridge Analytica’s presentation.

When asked to comment by email in August, IDEIA CEO Mauricio Moura said these sections of the pitch deck were made by a former employee. “We feel sorry for that mistake mainly because our values are intrinsically opposite from the mentioned company,” he wrote. “We are fully against those ‘anything goes’ practices. No mistake in a power point presentation will change our ethics, transparency and good practices.”

But in an earlier phone conversation, in July, Moura channelled Nix in describing the power of personality-based targeting. When asked to give an example of such targeting, Moura suggested pro-gun communication. A traditional person could be targeted with messages about a grandfather teaching subsequent generations to hunt, while a more neurotic type would respond to messages highlighting the threat of a break-in, he said. Nix gave the exact same scenario four minutes into his 2016 presentation.

Step one: The personality algorithm

IDEIA doesn’t only mimic Cambridge Analytica’s language: Both companies use similar methods of determining personality based on social media activity.

When IDEIA’s digital vice president Moriael Paiva met with Quartz in June, he explained that the company owns a database of 10,000 people who have consented to take personality tests and provide their social media data. IDEIA trained an internal algorithm to identify correlations between personality types and Facebook likes based on this 10,000-person database, explained Moura. This allows IDEIA to identify personality types of those outside their database using Facebook likes.

This is the same method Cambridge Analytica used to determine personality, though the London-based company claimed to own a larger database. Researchers can connect social media data and personality thanks to the work of Stanford psychologist Michael Kosinski, who published papers in 2013 and 2015 showing that Facebook likes can be used to accurately predict personality. In 2017, he showed that advertisements targeted to these personality traits were more effective.

Both Paiva and Moura said those in their internal database gave detailed consent according to GDPR standards. Under that law, survey participants would have to give explicit consent not just to fill out the personality test, but to allow IDEIA to evaluate their social media data and use this information to target political content, said Gabriel Voisin, a lawyer at Bird & Bird and GDPR expert.

IDEIA created the database in Brazil, which isn’t subject to GDPR, though the country recently introduced a law that requires similar levels of consent. “I’d be very interested to see what language they were presented with when those users said yes,” Voisin said. IDEIA did not respond to Quartz’s request to provide the language used when it asked for such consent.

Step two: Monitor social media

IDEIA keeps track of widespread social media activity to understand clients’ audiences. In the slide below, IDEIA offers to collect and monitor data from Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

While these companies provide APIs to give limited access to anonymized and aggregated data, all three social media companies have terms designed to restrict mass data collection. Facebook has a total ban on “scraping”—defined as a third party collecting data from a website or app without direct access to its database—without express written approval. Major social media companies prohibit third parties from scraping publicly available data, confirmed Voisin. “[Collecting data] would put you in breach of their terms right away,” he said.

According to Moura, IDEIA collects data that is “open” on Facebook, such as public posts and likes. “We don’t scrape individuals. We scrape words, we scrape mentions, we scrape likes,” he said in a phone call in July. In response to Quartz’s email request for comment in August, Moura contradicted this. “We have never done ‘scraping’ and only collect information through regular APIs,” he wrote.

Social media monitoring can also come into conflict with international legislation. For the use cases IDEIA articulates, GDPR would prevent the company from collecting social media data from their EU clients’ databases without explicit consent; either IDEIA or their clients must get such consent for IDEIA to monitor existing databases. IDEIA did not respond to questions about whether they or their clients asked for consent in these cases.

“It’s a big issue when you use data that’s posted on social media. Users don’t understand that this data may be used and analyzed by third parties,” said Gaffiot. “According to GDPR, they have the right to know.”

IDEIA claims to collect data only in aggregate, which is a method used to keep data anonymous. However, it is difficult to collect truly anonymous data; GDPR states data is only anonymous if it’s impossible to identify someone based on that aggregate data, even when cross-analyzed with other data. “Under GDPR, the most efficient way to attest of the compliance of an anonymization technique such as aggregate data is to issue a privacy impact assessment which is usually conducted by IT experts and lawyers,” Gaffiot wrote in an email. IDEIA has not issued a privacy impact assessment, according to Moura.

GDPR is not a straightforward law; many of its terms are being tested and refined by specific cases that go before European courts. Companies carry the burden of responsibility to ensure they don’t accidentally fall afoul of the law while dealing with such complexities.

Given the shifting understanding of GDPR, IDEIA could argue that the company is abiding by the legislation, said Gaffiot. But political opinions are considered sensitive data under GDPR, meaning that companies face a higher burden to prove that they need to collect such data, and have done so fairly. Overall, a European court would be unlikely to permit IDEIA’s practices, she said.

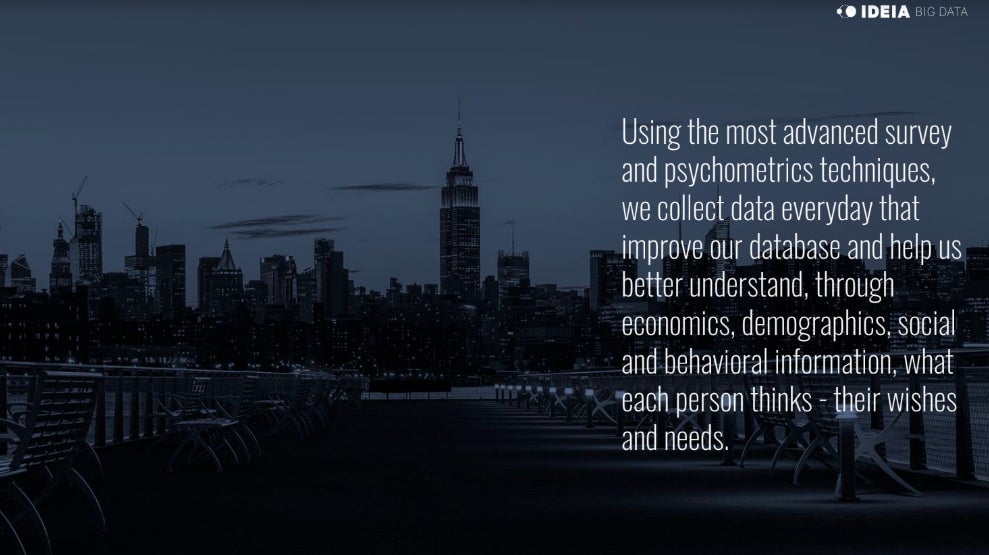

Step three: Sending messages

In addition to creating Facebook content, IDEIA offers WhatsApp messaging. In the pitch deck slide below, under “Clusterization and gamification,” IDEIA promotes a service called “Group formation / WhatsApp distribution List (Bulk or Organic).” WhatsApp uses the term “bulk” to describe the practice of blasting out WhatsApp messages en masse, whether with automated bots or cheap human labor. The practice is banned internationally by WhatsApp’s terms of service.

IDEIA offered inconsistent answers about its pitch deck’s mention of “bulk” messaging. “Sometimes the client has their own database and they want to send a message to that database,” said Moura in a July phone call. “Maybe that’s it… it’s the client’s list.” Though Moura said it would be “organic” to message a client’s database, sending out messages en masse is considered “bulk” regardless of whether they’re sent to a client’s database or not, and is therefore banned by WhatsApp. When later asked in an email about the phrase in IDEIA’s pitch deck, Moura did not comment on bulk versus organic messaging. “It basically means organizing group of supporters. Only supporters with full opt-in. Those groups share content and receive messages from several known numbers. Nothing massive involved,” he wrote.

In the July call, Moura also said IDEIA uses bots to send out bulk messages to clients’ databases, which is prohibited by WhatsApp. He contradicted this in the later email. “For the record, sorry if you did interpret me wrongly. No bots involved,” he wrote.

Under Europe’s GDPR data protection law, people have to voluntarily sign up to receive messages. The same law applies to political groups in Brazil, where IDEIA is based. Caio Machado, a policy and ethics researcher at the Institute for Technology and Society of Rio and the Oxford Internet Institute, said that the scale required for bulk WhatsApp messaging would be difficult if the company was only messaging those who consented. “The issue here would be how are these groups formed—is that through the sales of personal data, or would people have to sign up?” he said. Machado said he was concerned by IDEIA’s overall practices: “I’m not completely comfortable with the ethics of it or the legality of it.”

It’s impossible to fully assess the legality of these practices based on IDEIA’s responses to Quartz’s questions. The legality of each act also depends on where and when the company applies such techniques, as data laws differ internationally and interpretations of newly-passed legislation vary. Moura said the company complies with GDPR and only communicates with people in their clients’ database who consent to be messaged.

A widespread phenomenon

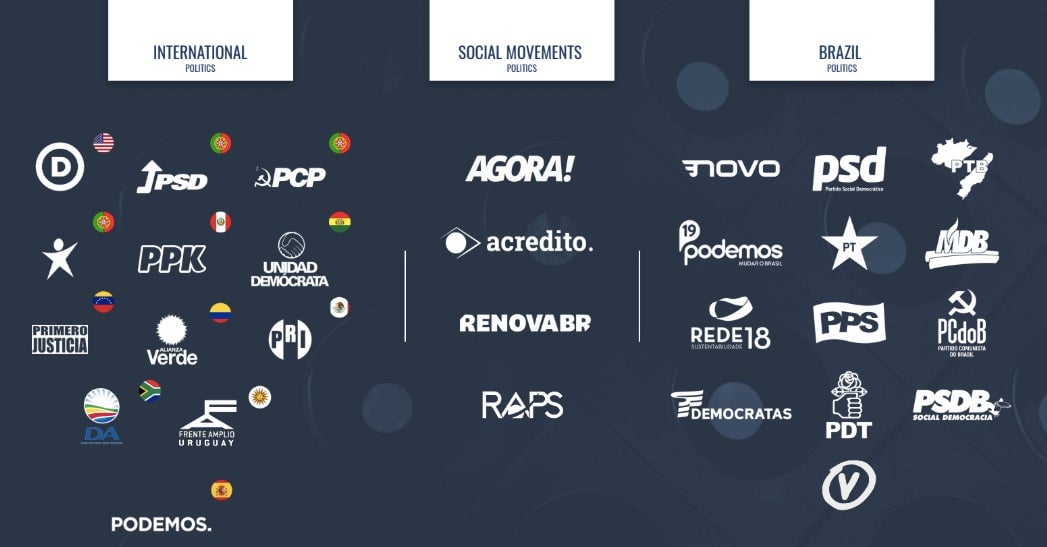

IDEIA claims to have worked with dozens of political campaigns internationally. The pitch deck presents “some of our clients around the world,” including the Democratic party in the US, Podemos party in Spain, the Social Democratic Party and Labour Party in Brazil, South Africa’s Democratic Alliance, the Communist Party and Social Democratic Party in Portugal, and the Unidad Democrata in Bolivia.

In another slide, the company claims to work with many international companies, including UBS, Credit Suisse, and Santander. It’s not clear what IDEIA’s role was or what methods they used if, as they claim, they worked on behalf of these political groups and companies. The US Democrats did not respond to a request for comment.

IDEIA’s methods are unlikely to be unique. Several technology and privacy experts see the IDEIA pitch deck as an unusually honest presentation of increasingly commonplace, but secretive, political targeting methods. “All along I said Cambridge Analytica was emblematic of how political marketing works,” said Chester.

“We’ve seen elements of these tools being used in North America, in Europe, they’re pervasive,” said Wright. Tactical Tech has published several reports detailing campaign use data and personality quizzes for political persuasion, but these reports often have to read between the lines, said Wright, as companies are not typically explicit about their use of personality tests or social media analysis. IDEIA, he noted, has no mention of personality-based targeting on its public website.

The process of interpreting and enforcing data law is a challenge. Though Cambridge Analytica faced widespread condemnation when its practices were uncovered in 2018, the US Federal Trade Commission only announced it was taking action against the company last month. One year and four months after Cambridge Analytica was exposed, the company was accused of collecting Facebook data through “false and deceptive means.”

Thanks to the uneven development of data law, political misuse of data can fall within the lines of legality. This is as much of a concern as illegal behavior, said Wright. Politicians have long crafted messages to appeal to segments of the population, emphasizing family-friendly policies to parents and stronger pension plans to older voters. Psychological profiling goes a step further, allowing politicians to craft the tone and emotional nuance of their messages to appeal to people’s personalities—and, ultimately, influence their vote.

Graphics by Youyou Zhou.