How Sequoia Capital is trying to avoid taxes on over a billion dollars in Indian investments

By 2013, Sequoia Capital, one of America’s most vaunted venture capital firms, had invested $1.2 billion in more than 75 Indian companies with combined revenue of more than $3.5 billion, the company wrote that year in a draft memo to potential investors.

By 2013, Sequoia Capital, one of America’s most vaunted venture capital firms, had invested $1.2 billion in more than 75 Indian companies with combined revenue of more than $3.5 billion, the company wrote that year in a draft memo to potential investors.

The Silicon Valley institution, an early investor in the likes of Apple and Google, made those Indian investments via a complex corporate structure based offshore in Mauritius, according to hundreds of leaked documents reviewed by Quartz that are known collectively as the Mauritius Leaks. Sequoia used that structure to legally avoid US and Indian taxes, says Reuven Avi-Yonah, a leading tax law professor at the University of Michigan, who inspected some of the files at Quartz’s request.

The files were among 200,000 documents from offshore law firm Conyers Dill & Pearman’s former Mauritian branch, which were anonymously leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), and shared with international media partners, including Quartz. A tiny former French and British colony in the Indian Ocean, Mauritius sells itself as a “gateway” to India and Africa for multinationals, offering extremely low tax rates and tax treaties with dozens of mostly poor countries.

The leaked Sequoia documents offer a rare detailed look at how global companies use venues around the world—even far-flung islands like Mauritius—to get the most favorable tax treatment for their activities. This is not a new trend, and an analysis of the documents doesn’t suggest that Sequoia did anything illegal. But the details reveal the contortions some companies go through to leverage loopholes that lower what they or their investors pay in taxes.

Developing countries such as India have long campaigned against Western multinationals making handsome profits in their own countries while paying as little as possible in taxes. The Tax Justice Network, a research and advocacy group, estimates that multinationals shifting profits to tax havens costs the world’s governments more than $500 billion per year, with poorer countries losing the most as a percentage of GDP. Efforts to close loopholes in the global tax system have historically foundered due to US opposition, but India is leading dozens of developing countries—which are generally more dependent on corporate taxes—in an effort to force multinationals to pay more tax in the countries where they make their money.

Indian law enforcement has leveled its gaze at Sequoia’s operations in recent years. In 2016, authorities raided the company’s offices in Bengaluru as part of a tax evasion investigation into Vasan Healthcare, one of Sequoia’s portfolio companies. Sequoia said a few days before the raid that it was cooperating with the probe. India’s Income Tax Department is now prosecuting Vasan in several cases in a special court for economic offenses. Two years later, Bloomberg reported that authorities were examining whether Sequoia had helped launder money for the son of India’s former finance minister by buying shares in Vasan from him at a premium. Both father and son are reportedly facing trial in New Delhi, but it’s unclear if Sequoia will feature in the case.

Sequoia hired Conyers’ law firm to advise on its Mauritian entities. The related documents, dated between 2012 and 2014, don’t show how much money the structures saved Sequoia, but they reveal at least two cases that seem engineered for tax avoidance, according to Avi-Yonah. Alongside Conyers, they employed lawyers at prominent tech law firm Goodwin Procter and accountants at Big 4 giant PwC. The leaked documents show no indication that Sequoia had any full-time staff permanently based in Mauritius.

Sequoia’s US investors include retirement funds and university endowments, on whose behalf it ultimately dodges these taxes. It’s unclear, however, who Sequoia India’s main beneficiaries are. The biggest Sequoia India shareholders listed in the Mauritius Leaks are a handful of anonymously-owned firms all registered at the same PO Box in the Cayman Islands.

A Sequoia India spokesperson told Quartz in a statement that it is common practice for Indian private equity and venture capital industry to be “domiciled” in Mauritius.

“Sequoia India holds itself to a high bar for compliance with respect to tax and other regulations, and has consistently sought expert, internationally recognized legal and tax counsel over the years to ensure its funds operate within financial and legal regulations,” the spokesperson said.

Case one: The “Singapore Mirror”

In 2010, Sequoia became one of the first two investors in Druva, a cloud security startup based in western India. So far it looks like an excellent investment: By 2019, the firm was a Californian unicorn, headquartered in Sunnyvale. It raised a round of $130 million this year to put its valuation north of $1 billion.

Druva, it turns out, had actually been registered in the tax haven of Singapore for many years, according to a 2013 email chain involving Sequoia India’s then-finance controller R Narayanan, Druva’s then-vice president for finance Robert Mally, and their lawyers and accountants. To move the firm from India, Druva restructured itself through a complex process into a new Singaporean firm, and then set up an exact mirror of the original company’s ownership setup. Sequoia’s portion of those shares was signed over to two of its Mauritian firms rather than its Indian investment vehicle, meaning they avoided Indian capital gains tax, according to Avi-Yonah.

The whole setup is a “pretty aggressive” case of tax avoidance, Avi-Yonah says. “It’s pretty clear that the mirror has no reason to exist but to avoid Indian tax,” he said. “It’s a pure shell. That’s pretty clear from the way the documents are crafted also—there’s nothing happening in Singapore, as usual.” A Druva email to its lawyers states that the move to Singapore was made for “business reasons” rather than tax reasons, but Druva’s own statements seem to confirm Avi-Yonah’s thesis that they did not have an active presence in Singapore at the time. Druva announced this year that it was opening a “new office” in Singapore as part of a “rapid expansion” in the Asia Pacific region. A spokesperson for Druva declined to comment on this article.

However, the move to Singapore raised the specter of being taxed in the United States. The US government considers any firm with more than 50% American ownership to be a US company for tax purposes. With Druva seemingly raising more funds from America, there was a risk it could surpass that 50% mark and investors could be liable for US taxes. So Sequoia wanted to transfer its shares back to its original Indian investment vehicle. (It’s unclear why this would have a different level of US ownership, but Narayanan wrote that they were transferring the funds back so that the Singapore restructuring could “be considered a tax free transaction in the hands of US investors.”)

As Sequoia’s lawyers prepared to draw up an agreement for one of its companies to buy the Druva shares from another one of its companies, the accountants stepped in. When Sequoia checked with PwC’s India office, they said there was a risk that New Delhi might want to tax any share purchase agreement, and recommended they transfer them as a gift. It’s unclear if, or how, the transaction was eventually made—the email chain ends with Narayanan checking with Conyers if the gift would comply with Mauritian law. PwC declined to comment on this piece.

The actors involved are clear that the machinations taking place after the company had moved to Singapore were aimed at avoiding tax. “We would need PWC to confirm that this outcome would maintain the reorganization as a non-taxable transaction,” Mally wrote at the beginning of the lengthy email chain. “Further, we would need confirmation that the transfer/sale of shares between the above entities would not be a material taxable event.” Narayanan later explained to two Sequoia colleagues: “This is primarily being done to ensure the Druva restructure does not result in it becoming taxable” for Sequoia India’s limited partners.

Conyers declined to comment on confidential client communications, but noted that it “strictly adheres to the laws of all the jurisdictions in which we operate and complies with legally applicable standards issued by internationally recognised bodies.” Mally and Naryanan didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Case two: The canceled loan

It was December 2012. US president Barack Obama had just been re-elected, dashing hopes that George W. Bush’s tax cuts would be renewed after expiring at the end of the year. Sequoia decided to get ahead of expected tax code changes by booking outstanding income before 2013 started.

On Dec. 18, its Mauritian lawyer received an email titled “Urgent: Sequoia MFC [loan] acceleration.” “Sequoia would like to engage in some minor restructuring of certain obligations with respect to one of the India funds for US tax reasons,” wrote Brian McDaniel, then a Hong Kong-based lawyer at Goodwin Procter. It’s not clear exactly which changes they were expecting to the US tax law.

The request: to cancel a $1.67 million loan agreement made between two of Sequoia’s Mauritian companies. Though not made explicit in the emails, Avi-Yonah says the most likely reason for the original loan was to avoid Indian taxes. The loan, he suggests, was never really a loan, but a dividend in loan’s clothing.

Avi-Yonah says multinationals have often used a loan-dividend scheme to avoid taxes. This is how it works, he said: A company makes a nice profit in a foreign subsidiary like India, and it wants to pay some of that money to investors. “The problem is that if they just declare a dividend, it would be subject to a 15% withholding tax [in India] according to their treaty, so you don’t want to do that. So you set up a loan,” he said. Then the company can cancel the loan, and the shareholders never repay the money. The Indian authorities would look at the document, see it’s a loan and not tax it. The US, however, recognizes these kinds of loans as dividends and taxes them. That means the company would need to cancel the loan agreement at the most tax-efficient time—seemingly in this case, just before taxes are hiked.

In the leaked emails, Sequoia’s lawyers and accountants discuss canceling five other loan agreements in different jurisdictions, though—as in the Mauritius case—they don’t say whether the loans were originally made in place of dividends.

Omri Marian, a tax law expert at the University of California, Irvine, said Sequoia canceling the loan is only “problematic” if it had intended to do this all along. Having reviewed the emails, Marian said he didn’t see any indication that “it was planned from the get-go,” seeming instead to be a response to an expected change in US law.

Offshoring ain’t easy

Such offshore schemes aren’t without their tribulations.

A lengthy 2013 email chain whose only goal was to arrange a meeting was received by four lawyers, three administrators, two accountants, and two other Sequoia officials. The issue: To fulfill both Mauritian law and the company’s statutes, they had to hold both a “substantive” shareholders’ meeting and a “statutory” one.

The year before, many of the same people had received an email with another hitch—one of the Mauritian companies only had $7 to its name. Under Mauritian law, it needed $35,000. They fixed the problem by simply issuing new bonus shares out of Sequoia India’s capital reserves. There are no legal or tax avoidance issues here, but “it seems a very cheap way of satisfying Mauritian authorities that the company is real—to put $35,000 into it given the sums involved [in Sequoia India’s investments],” Avi-Yonah says.

Other areas of Mauritian law proved more nettlesome. When setting up its fourth Indian fund in 2014, Sequoia battled against a Mauritian provision that places extra burdens on companies with more than 99 shareholders. Top officials weren’t pleased. “If this is the best we can do, I guess we will have to go with it,” Sequoia US CFO Marie Klemchuk wrote in one email. She added in another: “If the 99 issue goes away, pls let me know asap as we did not invite probably a dozen+ [limited partners] to keep under this headcount.”

They discussed solving the problem by having investors use special purpose vehicles or by starting a parallel fund, but seemed to eventually settle on a tactic oft-relied upon by multinationals in tax havens: asking the authorities to give them an exemption. The emails show lawyers drafting the request and officials heavily leaning towards sending it, but the correspondence doesn’t show whether it was eventually sent, or if it was granted.

The case is indicative of the “deal with the devil” that jurisdictions make when becoming a tax haven, says Alex Cobham, CEO of the Tax Justice Network, an advocacy group. “You’re agreeing to provide terms that multinational companies or the Big Four accounting firms or major tax law firms are demanding,” he said. “Once you start down that road and attract a certain amount of that business, you’re then much more vulnerable to the next request because you know that any benefits you’re getting can go away just as quickly as they came if you don’t play ball.” He cites major accounting firms persuading Britain to pass a law allowing companies to form as tax-avoiding Limited Liability Partnerships by first getting nearby tax haven Jersey to do so. The UK government then caved at the prospect of big companies decamping to the Channel Islands.

Sequoia doesn’t make any threat to leave Mauritius if the exemption isn’t granted, but an email from McDaniel suggests its lawyers were very much aware of the dynamic. “As a matter of political economy, the authorities have some incentives to show flexibility and grant the exemption,” McDaniel wrote. “Recall that Mauritius gains a great deal by being an offshore financial center and wants to be attractive to global investors.” Both McDaniel and Goodwin didn’t respond to emailed requests for comment.

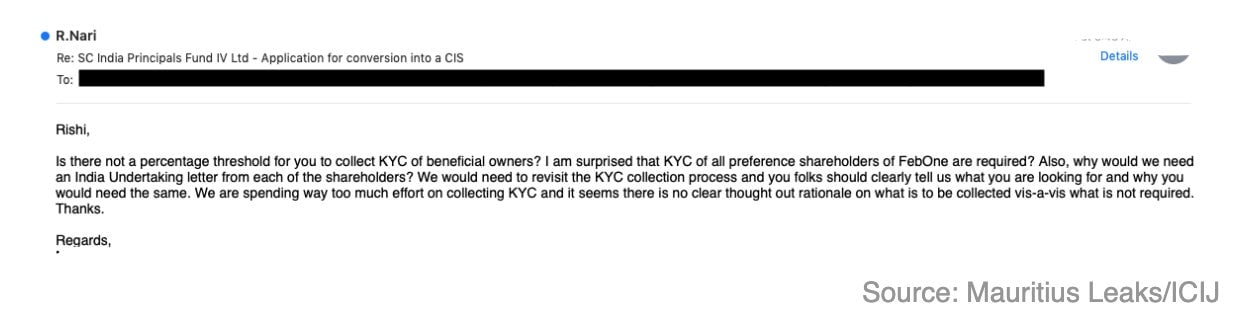

Required anti-money laundering checks also appeared to frustrate the company. While there’s no evidence in the leaked documents that laundered money passed through Seqouia’s funds, an email from Narayanan suggests it wanted to spend less time on so-called Know Your Customer (KYC) checks. “We are spending way too much effort on collecting KYC and it seems there is no clear thought out rationale on what is to be collected vis-a-vis what is not required,” he wrote in an email to Sequoia’s Mauritian company administrators, as they hurried to set up its fourth Indian fund in 2014.

The email “raises questions on whether multinationals are taking KYC obligations seriously given that it seems this person may be more concerned with meeting arbitrary thresholds than attempting to do effective due diligence on business partners,” said Mark Hays, the anti-money laundering campaign leader at Global Witness, an anti-corruption nonprofit.

Despite the hassles, Sequoia India seems to have been pleased with its offshore lawyers. Narayanan even passed Conyers some business, introducing one of the lawyers via email to a “good friend.”

“[He] was looking for introductions to a nice law firm in Mauritius and I could not think beyond Conyers,” Narayanan wrote.

Read more of Quartz’s reporting on how the Mauritius Leaks expose global tax avoidance.