Uber made a blueprint for safe self-driving cars it wants the rest of the industry to follow

Uber’s future depends on safe autonomous vehicles. The money-losing company is attempting to transition from costly human drivers to driverless cars. On July 16, it announced the industry’s first “safety case,” a universal framework for developing safe driverless vehicles, and it wants the rest of the industry to join in.

Uber’s future depends on safe autonomous vehicles. The money-losing company is attempting to transition from costly human drivers to driverless cars. On July 16, it announced the industry’s first “safety case,” a universal framework for developing safe driverless vehicles, and it wants the rest of the industry to join in.

Uber is still recovering after one of its self-driving vehicles killed a pedestrian in Tempe, Arizona in 2018, one of the first recorded deaths by an autonomous car, despite having a safety driver behind the wheel. That prompted a nine-month shutdown of its self-driving program, two investigations, and a drastic rethinking of the company’s efforts to ensure the public feels comfortable stepping into an Uber vehicle driven by algorithms. “We recognize trust will have to be earned,” Noah Zych, chief of staff for Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group, said at the Automated Vehicles Symposium in Orlando. “We have to earn back the trust. The first step is to be open, transparent, and sincere about how we do that.”

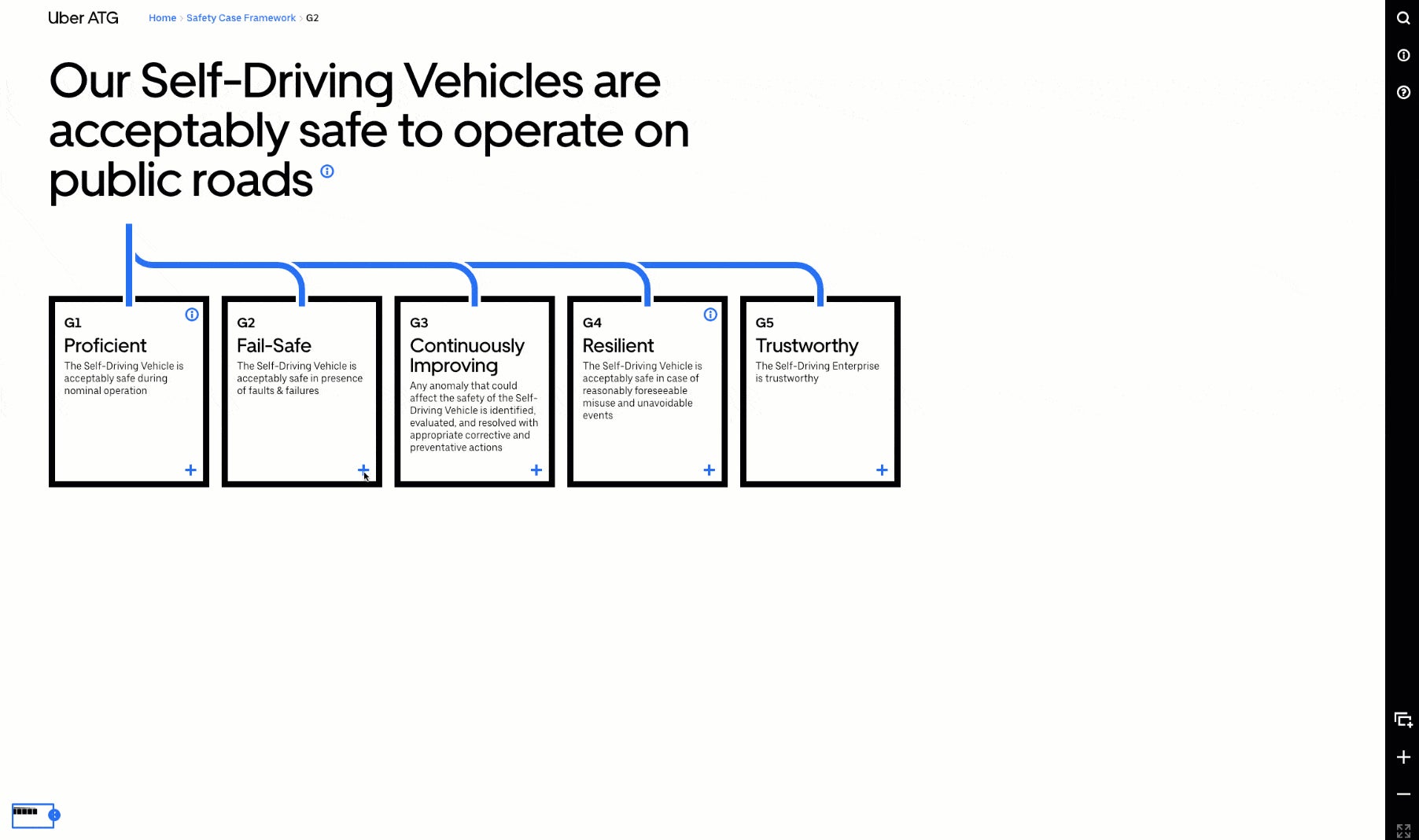

Uber’s has shared its blueprint in hopes that it will become the industry standard for developing safe autonomous systems. It starts with a premise, that the company’s “self-driving vehicles are acceptably safe to operate on public roads,” and derives a comprehensive series of steps that must be developed and verified to meet it.

Rather than separately address the hardware, software, testing, simulation, or human training as separate components in an automated system—something standardization bodies like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) are already doing—it places them within a single, larger safety framework. Uber’s safety guidelines end up looking like a cross between a checklist and a decision tree, with each item flowing from that premise that its vehicles are safe to drive on public roads.

The aerospace, rail, and nuclear industries also break down safety problems into their essential, interrelated components. Some of the materials in its guidelines, Uber said, can be found in a typical airline manual. While those industries are heavily regulated and also have the potential for mass fatalities, there’s a crucial difference: no one yet knows was “safe” self-driving technology look looks like yet.

Without real-world experience, it’s difficult for regulators to simply mandate best practices in the burgeoning autonomy industry. So Uber (and others) are promoting an approach that certifies a framework to operate within, rather than a set of specifications, as the technology evolves at a blistering pace. This should theoretically allow regulators to then set guidelines (such as benchmarks on what they will accept as the rate of failure in these machines), while Uber and other companies ensure they meet them.

Today’s auto industry follows this model. “We can still maintain the self-certification model, but we’re not relying on the government to give a stamp of approval,” Nat Beuse, Uber’s head of safety and former National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) safety official, told Quartz. “The idea we’re trying to put forward today is not a single company approach, it’s an entire industry approach.”

That has the advantage, theoretically, of ensuring the highest degree of safety amid massive technological uncertainty. Any organization or individual can borrow and modify the safety case Uber has set out. A “master” copy will reside with Uber, but the company says it will continually update the case and hopes to formally partner with organizations to prove it out. “We recognize that what we’ve put out today is imperfect it will take time to finalize this,” Zych said. “We’re not going to get to standardization until…we can show what’s working. It’s much harder to standardize around a theory versus what’s been shown to be effective.”

And mistakes will still happen. The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has decades of experience validating how to build a safe airplane. It is a process that has worked extraordinarily well at bringing down fatalities in commercial aviation. Today’s airline fatality rate is now a fraction of what it was in 1950s. Statistically, you could fly every day for four million years on average before dying in a fatal crash.

But recent oversights such as the FAA’s apparent over-reliance on manufacturers to “self-certify” their aircraft, as it allegedly did in the deadly Boeing 737 Max 8 crashes, threaten some of these gains. In Boeing’s case, the company overlooked key safety considerations that turned a preventable technical mistake into a systematic failure that may have contributed to two airplane crashes and 346 deaths.

In theory, Uber’s comprehensive safety case accounts for such problems. It’s designed to integrate human, technical and environmental factors that would feed into such problems on the road. Self-driving cars are still in their infancy. As the industry starts to define what “safe” looks like, and how to get there together, Uber wants to start drawing the roadmap. Now, it needs to convince others to join them.