There’s a global movement of Facebook vigilantes who hunt pedophiles

Tony Blas is a plumber in his mid-thirties who lives in Queens, New York. He has two young daughters. In his spare time, he hunts for people who try to groom children online and lure them into sex.

Tony Blas is a plumber in his mid-thirties who lives in Queens, New York. He has two young daughters. In his spare time, he hunts for people who try to groom children online and lure them into sex.

We first met on a sweltering summer day. I suggested a pizzeria around the corner from Blas’ house, but when I was sitting there waiting for him, I realized it might be uncomfortable to talk about pedophiles with children eating their slices at the next table. We went to the park across the street, and sat on a bench.

“I could’ve stayed in there,” Blas said. He didn’t care that the other patrons might overhear details of our conversation.

I shouldn’t have been surprised at his lack of discretion, since he regularly shares his work with his 40,000 followers on Facebook, via a page he founded called “Team Loyalty Makes You Family.”

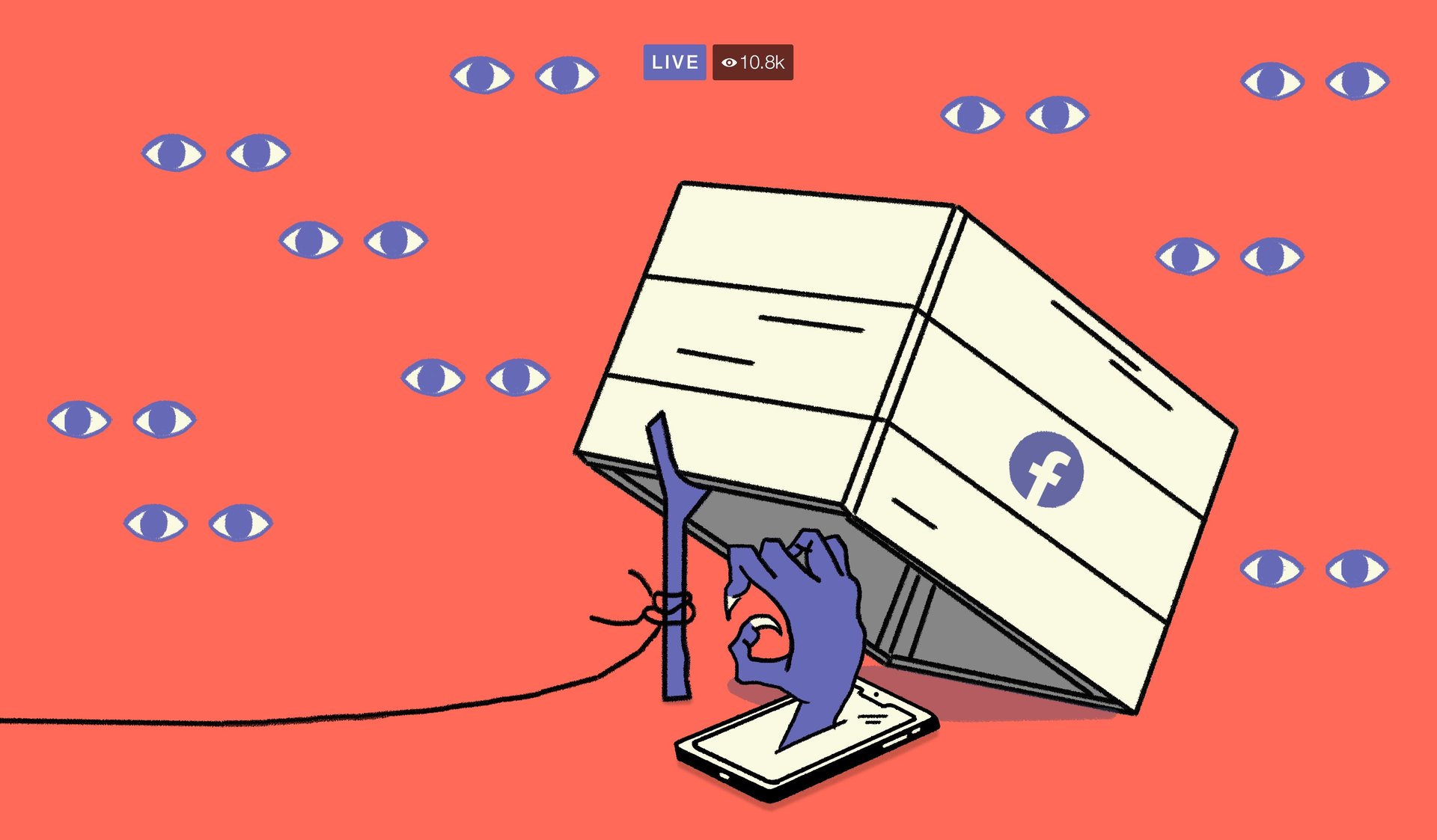

He is one of dozens of people around the world who’ve created communities on Facebook which—in the name of street justice—stage real-life sting operations to name and shame people they suspect of being child abusers. They broadcast all of it live from their phones.

“Pedophile hunting” or “creep catching” via Facebook is a contemporary version of a phenomenon as old as time: the humiliating act of public punishment. Criminologists even view it as a new expression of the town-square execution. But it’s also clearly a product of its era, a messy amalgam of influences such as reality TV and tabloid culture, all amplified by the internet.

The hunters are responding to very real dangers lurking online. Drawing a child into sex can be as easy as an online chat, and child pornography has proliferated with the rise of the internet. It’s not difficult for people to view the problem as a vast specter hovering over children everywhere, even though (or perhaps because) accurate statistics on grooming are hard to come by.

But using social media to name and shame potential offenders is deeply problematic. It has led to a number of suicides in several countries. The hunters’ efforts can unravel into violence. They can be counterproductive, endangering ongoing investigations, and the evidence obtained from stings is legally shaky. The hunters harness social networks like Facebook to unleash the all-powerful ostracism of the universally abhorred figure of the child abuser, but they might not have all the facts and context. They have little regard for due process or expectations of privacy. The stings, live-streamed to an engaged audience, become a spectacle, a form of entertainment—a twisted consequence of Facebook’s mission to foster online communities.

To Catch A Predator

, redux

Before Facebook became the juggernaut it is today, there was a popular reality television show called To Catch a Predator, which aired in the US between 2004 and 2007. Show host Chris Hansen would take viewers through sting operations he carried out in cooperation with an online vigilante group called “Perverted Justice.” Adult decoys would pose as children, chatting with the “predator” on online message boards in order to eventually get him to meet up in real life, only to be exposed by hidden television cameras, and later arrested by collaborating police.

One 2012 study examined why people joined pedophile-hunting chatrooms. Many said they did it out of a sense of injustice and parental concern, but more than half cited To Catch A Predator. The series showed audiences how horrifyingly easy it was for adults to lure children online, but it also gave them the idea that they could try to do something about it.

In 2019, “Perverted Justice” posted that it would cease decoy operations, claiming more than 600 convictions. “As the internet changed, elements like twitter (sic) and social networking in general has spread the problem wide and thin,” founder Xavier Von Erck wrote in the post. “Internet predators are no longer confined to mostly a few deep wells as they were when we started up.” He added that the group has been less able to keep up technologically.

Social media may have made it easier for pedophiles to find their targets, but it’s also led to a proliferation of people hunting them down. Operations like “Perverted Justice” were replaced by dozens of groups around the world—many of them seemingly less organized and more amateurish, whose main hub of operations is Facebook.

The platform gives the hunters greater exposure than the obscure message boards they depended on in the earlier days of the internet. There’s also no need now for expensive cameras and a TV network time slot to spread the word.

The suave TV host is replaced with a local plumber, or a long-haul trucker, broadcasting shaky footage from their phone.

A global phenomenon

In the UK, these groups have been “hunting” and publicizing their “busts,” in hunter lingo, since roughly the start of the decade. There are multiple UK-based hunter communities with hundreds of thousands of followers. The British media have been breathlessly following their shenanigans, and their rocky relationship with law enforcement. They’re popular in Canada, and imitators have popped up in other countries, like Australia. In the past two years, they’ve started appearing in the US, seemingly influenced by their counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic. Blas, for example, says he started his operation after watching a sting from a UK group in his feed.

An NBC investigation in January tracked down about 30 active hunting groups in the US, and Quartz was able to independently find 24 such groups in July, and a variety of pages and groups that call themselves “hunters” as well, but usually just share information about sex offenders caught by police.

It’s unclear why exactly this phenomenon popped up when it did, but in the UK, for example, there’d been a number of high-profile cases that emerged in the early 2010s, like the Rotherham scandal, where more than 1,500 child victims were found to have been abused and trafficked by a gang over a 16-year period. There was also the case of Jimmy Savile, the BBC star who sexually abused hundreds of children. The case brought more attention to the problem of the sexual exploitation of children, sociologist Daniel Trottier, a media and communications professor at Erasmus University Rotterdam, told Quartz. But the British tabloids, which have a strong presence in the country, have been drumming up the issue’s salience years before that.

In 2000, for example, following the murder of the eight-year-old Sarah Payne, the tabloid News of the World’s pedophile naming-and-shaming campaign helped spur a spate of vigilante attacks. Today, UK tabloids re-publish footage from online stings, headlines screaming things like, “WATCH: Perverted paedophile begs for mercy when he is cornered by vigilantes.”

Anti-pedophile vigilantism is generally a global phenomenon. In 2018, 11 people were arrested in Myanmar after a violent crowd formed demanding the police turn over to them a suspected pedophile. In Indonesia, a mob attacked and killed a man suspected of being a child molester in 2017. In India, rumors of child trafficking and pedophilia, spread on WhatsApp, have led to lynch mobs that killed at least 29 people.

The power of social media

The Facebook vigilante groups use similar tactics to their predecessors, but they function in a different internet universe. Almost everything that characterizes social media today helps these groups thrive, from the platforms’ emphasis on community and video, to the way they are saturated with misinformation and divided into filter bubbles.

It was easy for two hunters I spoke with to launch their efforts on Facebook. (They use YouTube as well, but both said their content would quickly get taken down on the video platform—although it’s not clear why). They already knew how to use Facebook. And it is exceedingly easy to find an audience.

Using Facebook makes the experience feel more familiar for viewers. Followers know how the site looks and functions, and it sanitizes the vigilante effort, taking it from dark, obscure folds of the internet to the social network that everyone uses every day. Facebook’s requirement for users to register with their real names might also boost the hunters’ credibility.

Jesse Weeks is 28, a truck driver, and founder of “Hunted and Confronted,” a vigilante group which has 18,000 followers on Facebook.

“People can see, ‘Hey, that’s my neighbor,’ ‘Hey, he’s my mailman,'” Weeks pointed out.

The content pedophile hunters post on Facebook is tailor-made to flourish there. It’s highly visual, which the algorithm rewards. By playing on people’s fears and moral outrage, it gets shared and re-shared. (The most shared English-language news story in the first three months of 2019 was a 119-word piece about a sexual predator). The busts offer tales of danger and vengeance, and there’s nothing the internet loves more than schadenfreude. The posts are often quickly amplified by local news, which latch onto the story of a pedophile in the community.

Followers cheer on the hunters, thanking them for doing “god’s work,” congratulating them, and cursing out the alleged predators.

Sophia Gabrielle Chery is 29, and follows “POPSquad Prey on Predators,” a page with 22,000 likes on Facebook, which operates, among other states, in Connecticut, where she lives. She doesn’t have children of her own, but she works as a nanny, and her brother, who has two children, owns a daycare. She shows her nieces and nephews the POPSquad videos, warning them to be careful about who they chat with online. Every time a new video is posted on the page, she gets an email alert.

To her, the value of the group is a no-brainer. “This is real. This is not a joke. They are getting predators off the street,” she said. POPSquad boasts 149 busts, and Chery was impressed when it took less than a day from a bust for the incident to be written up in a local newspaper. “It’s important to get it out there,” she said. “The more coverage the better.”

“We don’t need Chris Hansen because social media itself has now kind of usurped the mainstream media in a lot of ways,” said Stephen Kohm, a criminologist at the University of Winnipeg.

Predator hunting teams will sometimes work with each other, cross-posting busts and encouraging followers to follow the teams they are allied with. Blas works with a team in Tennessee, and for the last several months, has been splitting his time between New York and there. He said he even got a visit from a UK team.

With smartphones and the Facebook app at their fingertips, people can check in with the page at any time of day. These communities are active, and if you “like” a given page, or better yet, become a member of a group, your newsfeed can quickly fill up with its content. It likely helps that Facebook prioritizes “meaningful interactions,” which boils down to posts that garner back-and-forth comments, and content that is shared by regular users rather than publishers or brands.

This lands the user in a filter bubble that revolves around seeking out pedophiles, finding them wherever they might look, which is only made more powerful by the shared experience the user has with every other member of the group. People who feel a sense of rage over pedophilia can connect in ways they weren’t able to before.

“Humans for a long time talked to their neighbors, and we’re not good at doing that anymore,” Sarah Ester Lageson, a sociologist at Rutgers University who has studied why people join online crime watches, told Quartz. “This offers a space for people to scratch that itch.”

Instead of communities based on proximity, we now have “issue-driven” ones, she added. And crime is an easy thing to rally around.

Facebook capitalizes on this. The company’s mission is to “build community” and “bring the world closer together,” founder Mark Zuckerberg said in 2017, as he announced that Facebook would focus more on groups, which are some of the most active parts of the platform. The hunter communities often have both a public page and a closed or private group for their loyal fans.

Who are these “hunters”?

When we met, Blas wore cargo shorts, black work boots, and a big t-shirt emblazoned with the slogan, “Blood makes you related, Loyalty makes you family”, in reference to his group’s name. He had a bandanna on his head, shielding him from the August heat. He’s all New York—born in Brooklyn, living in Queens, dropping his R’s and stretching his vowels. While confrontational with “predators,” in conversations with me, Blas is a nice guy, ending a phone conversation by calling me “sweetie,” in a way that felt well-intentioned rather than unsettling.

He has a team of decoys, adult women who pretend to be minors. He claims that to construct their child alter egos online, they use either their own photos, or ones from family members, from whom they have permission. Among the apps the group uses are Tagged, an aging, but still active social discovery network, and Plenty of Fish, a dating app. He wouldn’t disclose other apps, but said the group used “pretty much any dating site, any child game that has communication either through text or voice.”

Blas typically doesn’t post screenshots of his chats on Facebook out of precaution, but many other vigilante groups let you follow along the spectacle from the very first message posted by a decoy.

“Team Loyalty Makes You Family” decoys start out with saying they’re 20 or 21 years old, and bored. When the target responds, the decoys “admit” that they are actually 13, 14, or 15. “Then we wait,” Blas said. “If they continue to talk, we sit and listen.”

The decoys take care to show the purported child’s innocence in the chats. The conversations go on for two or three weeks. Blas says this is purposeful. “I’m not here to ruin people’s lives if they don’t need to be ruined. I know people make mistakes, but if you’ve been on for two or three weeks talking, you had enough time to say, ‘I’m doing something wrong here.'”

When the two parties agree to meet, Blas picks a place, often in his own neighborhood. Like other hunters, he starts a broadcast on Facebook Live, often from his car, sometimes narrating an introduction to the perpetrator. Initially, he covers the video to make sure he has the right person. Then he confronts the “predator.”

“Who are you here to meet?” he asks in one video.

“Nobody,” the man answers.

“Do I show you a picture?”

“Why?”

“What do you mean why? This isn’t you?” he says, looking at his phone and pulling something up on the screen. The audience only sees his face.

“Yeah” the man answers, while his face is revealed to the viewers.

The conversation continues, with Blas quickly getting the man to admit why he is really there.

“What is a 44-year-old man doing meeting with a 15-year old?”

“I’m recording you for yours and mine safety.”

The man starts walking away, repeating “I understand” and saying he “only wanted to hang out” and that “he didn’t plan to do anything.”

“You came to my neighborhood, all the way from Middletown, New York, you came to my fucking neighborhood to meet a child. And you think that’s fucking okay?” Blas says.

The video has, as of July 2019, 7,000 shares, and 370,000 views, boosted by coverage in local media. The man turned out to be a high school teacher in upstate New York. A commenter says “He was my math teacher! Omg!!!”

The suspect was charged with attempting to endanger the welfare of a child by police and is awaiting trial.

After a serious car accident in his twenties, Blas says he became addicted to painkillers, and later heroin. He was once arrested for domestic battery, and served time in jail. He lost contact with his wife and daughter, but was eventually able to get back on track thanks to an organization that helps the formerly incarcerated.

His decoys, Blas says, are stay-at-home moms, spread out across several states. They’re “like my family,” he said. He met them on Facebook.

At first, Blas thought that “there’s no way there can be this many guys out there doing this,” referring to the predators. He decided to try out the hunt. “I downloaded an app, I made a post, and within three hours, I had a guy ready to meet.” The man wanted to have sex with a 14-year-old in the stairwell of a social housing building in Brooklyn.

His motivation is in part personal. Blas says he’d been a victim of sexual abuse as a child himself, at the hands of his mother. “I wouldn’t call it like therapy, but it’s helped me a lot with my anger, how to react to different situations.”

Then, he promptly voices the obvious. “Now it’s like I get to confront—not literally—but I get to confront one of these sickos that did something to a child that was done to me.”

Blas’s younger daughter, aged five at the time, asked him for a phone several weeks before our first interview. These days, he says, there’s no “white van driving around the block” that parents can tell kids to watch out for. “Right now it’s these guys are getting into your home without even kicking in the door. They’re sitting in the living room talking to your child.”

At this, he gets visibly aggravated. Adults are so lost in their phones, he says, they often won’t take a moment to check in with what their child is doing on theirs.

“People always ask, how are you not hitting these guys? How are you not just killing them?”

Ideally, he’d like his work to be formalized, to function like the bail bonds industry. In the US, bail bondsmen function as private actors who are authorized to capture criminal defendants. If the community is willing to help, Blas says, authorities should either fund these efforts, or at least allow them.

But in the end, whether someone is arrested and convicted isn’t that important. His goal is administering street justice, he says, not shying away from the term. The goal is that “a guy walks around the street and people know who he is.”

Weeks has somewhat different motivations. During a phone interview, Weeks says he grew up in a middle-class family and never experienced any sexual abuse. But he says he’s always been involved with kids, coaching the local Little League baseball team for example. He has two younger brothers, and has helped his mother raise them, he claims. He likes to keep his stings “as kid-friendly as possible,” avoiding swearing, so that children can watch it with their parents. As a trucker, Weeks has witnessed sexual trafficking and prostitution. He sees women getting into trucks with men 35, 40 years older than them. “I wonder how old they were when they started this,” he says.

The group that at one point was the largest predator hunting community in the US, Truckers Against Predators, was also founded by a truck driver. It makes sense. As Weeks notes himself, truckers often see evidence of sex trafficking during the course of their work. In fact, there’s a large trucker organization that trains drivers to recognize signs of trafficking and report incidents.

Truckers have a lot of downtime while on the road. It’s also a lonely line of work. With a cause like predator hunting comes a sense of mission—and a built-in community, said Karen Levy, a sociologist at Cornell University.

Weeks is adamant that dealing with online predators is best done through the criminal justice system. But police can’t focus all their resources on sex crimes, and what he can do—posting alleged offenders’ identities online—has an immediate effect. You just don’t know what might happen tomorrow, he says. Putting their faces out there is the “second best thing,” he says.

Several weeks after we spoke, Weeks was arrested on drug charges. According to prosecutors, he has an “extensive criminal history.” The hunters often have criminal records unrelated to their “hunting”—Blas has one, as does one of the more popular hunters Shane Coyle, and the founder of the hunter group POPSquad, Shane Erdmann.

The downsides and dangers

The hunters are not professionals, trained to pursue suspected abusers. The situations they find themselves in are highly tense, and often precarious.

“Offenders can be dangerous, particularly if they feel they’re being cornered,” said Victor Vieth, a former prosecutor and head of the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse in Virginia. The hunters risk their own lives, but the targets could also harm themselves, their own children, or any potential children they are violating, he added. Either party could be armed, particularly in the US, where gun laws are more lax than in other countries. And even if the hunter is behaving safely, those watching on Facebook might not.

After being “exposed” online, at least eight people have committed suicide in the last six years in the UK, at least one in Canada, and one in the US (in addition to a man who took his own life after being featured on To Catch A Predator). In July, the military publication Task and Purpose also reported that an online hunting group could have led to the suicide of a sailor.

There’s an entire genre of news stories in the UK media about pedophile hunter stings gone wrong, where they catch the wrong person, prematurely accuse someone of a crime, cause violent confrontations, or even get infiltrated by an actual sexual predator themselves.

Pedophile hunting, and the ways in which it goes terribly awry, can take on different forms depending on the cultural context, political discourse, and local issues. The Rotherham scandal involved Pakistani immigrants, so the conversation about it became about who should and shouldn’t be allowed into the country, Trottier noted. In Russia, often “the label of pedophilia, or a pedophile gets applied to sexual minorities,” he added. Under the guise of “pedophile hunting,” a notorious Russian ultranationalist group made international news in 2013 by luring young gay men into traps and brutally humiliating them, posting footage online.

In the US, there was the “Pizzagate” scandal, where a man who’d been radicalized on Reddit showed up armed in 2016 at a pizza parlor in Washington DC, believing a Democrat-run pedophile ring was operating on the premises. The trope of an all-powerful pedophile ring has been woven into the bizarrely complex QAnon conspiracy theory, which also thrives on Facebook.

Facebook doesn’t have a clear stance on vigilante groups. It took some of them down after the January NBC report, but others remained, including POPSquad. The NBC story details how a 20-year-old gay man who came to meet with a purported 14-year-old, instead encountered the POPSquad hunter. Shortly after, the man hung himself.

“We want people to use Facebook and our products to raise awareness about threats to public safety, including those who may pose harm to children,” a spokesperson told Quartz in a statement. “However, we do not want people to use Facebook to facilitate vigilante violence. That’s why we have policies against threatening real-world harm and to protect people’s privacy if they are being publicly shamed. We will remove content that violates these policies when it is reported.”

Facebook also doesn’t allow public shaming if any personally identifiable information like images of IDs or license plates are shared. People worried that their privacy is being violated by their images getting posted online can report an incident to Facebook for review, the company said.

It also added that it removes convicted sexual offenders from the platform and that it works with law enforcement and experts to eliminate content that exploits children.

The legal ramifications

Blas argues that he has more leeway than police officers do, because he doesn’t have to follow strict police regulations about how to conduct decoy operations. But those procedures are there for a reason.

“If they don’t have the authority to gather this information and they don’t use proper procedures, anything that they turn over is tainted,” said Brad Russ, director of the US National Criminal Justice Training Center, which trains law enforcement in responding to crimes against children. Officers who specialize in child abuse are trained step by step how to have a dialogue with a potential offender.

“Getting the information to law enforcement is great, but going out and doing it yourselves is a whole completely different story,” said lieutenant John Pizzuro, commander of the New Jersey Internet Crimes Against Children (ICAC) task force, which operates as part of New Jersey’s state police and the national ICAC network.

And regardless of who is conducting it, the legal line in any sting operation is blurry. If you don’t tread carefully, the whole effort might be deemed entrapment in the eyes of the law, meaning that the alleged perpetrator was tricked into committing a crime. Defense lawyers have claimed entrapment in past cases involving predator hunters. In 2011, a judge threw out a case against a man caught in a 2006 To Catch A Predator sting over entrapment. In the UK, a judge scrapped a case over similar concerns just last year.

For law enforcement, working with the groups is risky. “They become an agent and an extension of us,” Pizzuro said.

In court, the accused might claim that they knew they were talking to an adult, and that they were engaging in fantasy play. This scenario, orchestrated by police, played out recently in Canada, and the Supreme Court sided with the accused.

There are other concerns. “If you tip off the offender, even unwittingly, that might cause him or her to go out and destroy evidence that would be far more damning than anything you’ve discovered already,” Vieth said. And if you’re acting on your own, you might not know whether the police are already investigating the person you’re after. They may already be talking to them online, interviewing their victims, and then you’re undermining the official probe.

There might be other victims, Pizzuro added. The hunters actions’ might harm their safety, and hinder law enforcement’s ability to act on these other cases. “And they’re not trained to help those victims,” he said.

But sometimes, police will use evidence gathered by the vigilante groups, leading to arrests and convictions. Blas has an arrest under his belt; Weeks has multiple.

In the UK, a freedom of information request by the BBC showed that in 2017, in nearly half of the cases of a person meeting up with a child after sexually grooming them, police in England and Wales used information from unofficial “hunters.” It amounted to 150 cases, a seven-fold increase from 2015. The data came from 67% of police departments in the country.

Still, the relationship is very fraught, said David Wall, a criminology professor at the University of Leeds, because of the same procedural and safety concerns.

It’s hard to argue against the vigilantes’ cause: Child abusers prey on the most innocent in society, causing severe trauma for life. But letting emotions dictate responses to the problem is not productive, James Cantor, a Toronto-based psychologist and leading expert on pedophilia, told Quartz.

“Pedophilia is not a synonym for child molestation,” he said. “Pedophiles are the people who are actually, genuinely sexually interested, aroused by children in the way the rest of us are naturally sexually aroused by adults. They did not pick that, they were born that way.”

They can be taught to manage it, but you can’t change who they are.

Instead of shaming people—stigma being a doubtful deterrent—the most effective solution is getting them into treatment, Cantor said.

Just how common are pedophile predators?

It’s difficult to assess the prevalence of this problem. The spread of child pornography is undoubtedly on the rise, several experts told Quartz, its proliferation made easier by the internet. But there’s not a lot of specific data to draw on when it comes to the luring children online into sex.

The CyberTipline, run by the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, is where individuals in the US and online platforms like Facebook can report crimes against children. The number of calls is growing significantly every year, according to the center, with 10.2 million reports in 2017, and 18.4 million in 2018. The problem with these figures is that the organization doesn’t provide a breakdown of the alleged crimes, meaning child pornography, sexual molestation, sending unsolicited sexual materials, and other issues are all lumped together with grooming.

When it comes to online enticement specifically, most offenders reported to the CyberTipline (60%, the organization says) want sexually explicit images of children, while one third want to have sex with a minor. In 12% of reported incidents, either the victims or the offenders mention meeting in person—8% vaguely, and 4% more seriously, coordinating specific times and locations.

In the UK, the number of recorded sexual offenses against a minor flagged as “online crimes” has doubled between 2015 and 2019, according to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC).

Overall, the reporting rates for sexual crimes are low.

A large survey published in 2014 by the University of New Hampshire (UNH), a hub for research on crimes against children, showed that between 2000 and 2010, reports of unwanted sexual solicitations fell by more than 53% over the decade. And more generally, sex crimes against children in the US have been declining significantly in recent decades.

“I don’t see the evidence for a dramatically increasing epidemic,” said Professor David Finkelhor, author of the UNH report and expert on crimes against children. Law enforcement is getting better at detecting child pornography and catching offenders. There’s more awareness and education about sexual abuse than in past decades. Instead of chatrooms, kids may be on platforms where it might be easier for them to control who can reach out to them. Publicity around law enforcement busts might also act as a deterrent.

Just last September, police in New Jersey mounted online decoy operations of their own, resulting in 24 arrests of people for trying to lure children. In April, the state arrested 16 more in a similar operation.

The UNH data, however, comes from before the ubiquity of mobile phones and social media, and Pizzuro, the New Jersey ICAC commander, says that these operations point to an increasing, not diminishing, problem. More children are online, and “whatever game or app that children are on, that’s where the adults are going to go,” he added. Pizzuro says luring arrests in New Jersey have risen significantly recently, and the most troubling aspect is that younger and younger children—8, 9-years old—are able to take explicit images or videos at the direction of adults online.

But it’s never been easier to report incidents, and the volume of referrals from the CyberTipline has overwhelmed law enforcement, police experts said. ”It just comes down to resources because these proactive cases take time,” Pizzuro said.

A tool for surveillance and entertainment

Predator hunting groups are part of a larger ecosystem of online neighborhood and crime watches, which now includes Facebook, as well as various apps offered by large companies like Amazon. These include Nextdoor, where people post about local issues, including a “suspicious” man standing on the corner; Citizen, originally called “Vigilante,” which alerts users to crimes in their area reported to the police and encourages them to film the scene; and Amazon’s Neighbors, an app that allows users to share footage from their Ring video doorbells. (These apps have all faced accusations of encouraging racial profiling.)

Social networks and tech companies allow us to “really play dress-up like a cop, in a digital culture where you can build a whole community space to talk about it, think about it, share best practices and quasi-professionalize your volunteer service around it,” said Dara Byrne, professor and dean at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

Facebook Live, for example, is “a tool that can be used to enhance both community and surveillance and it’s free,” Byrne added.

The live-video feature on Facebook has from its inception been controversial for enabling people using it to broadcast violence, including murder, abuse, and suicide. It came under fire again this year, when a shooter in Christchurch, New Zealand streamed his murderous rampage on the platform. After the shooting, Facebook imposed a “one-strike” rule for live videos, where if a user violates its “most serious” policies once, they are banned from using the feature for a certain time.

Video is a crucial element of Facebook’s business strategy. And live broadcasts, which can last as long as two hours, are central to the hunters’ efforts.

Many of the hunters would never admit it, but to an observer’s eye, their work is often reminiscent of entertainment content. It requires a businesslike hustle, and reality TV is in the groups’ DNA, sometimes quite literally—Shane Coyle, a well-known hunter, used to be a reality show contestant.

Both Blas and Weeks are quick-talking, charismatic. The groups often sell merchandise, like T-shirts. Blas says money from the merch is used to cover costs, like new phones for the decoys, because they get used so much. Weeks says he even had sponsorship deals lined up.

And he has experience engaging audiences online. Before he started “Hunted and Confronted,” Weeks had another public Facebook page, which he says had several thousand followers. Called “Motiv8,” it was dedicated to messages of positivity, entrepreneurial spirit, and success. For that group, he also had a line of merchandise. He also claims that he was contacted by a production company to do a non-scripted television series following his sting operations, but the deal fell through for legal reasons.

In a 2009 paper about To Catch A Predator, Kohm, the criminologist, wrote about the power of shame in our pop culture. It’s what so much of reality TV is about, watching people make fools of themselves. Same for TMZ-style tabloid journalism, where the “gotcha” aspect is crucial. They may have higher aspirations, but hunter groups fall into the same tradition.

“I think it’s just deeply ingrained in humans to really enjoy watching other people suffer,” Kohm said. “It’s almost as compelling as watching an execution in the town square, it’s just a social execution.”

The realism helps. Reality TV is compelling because it offers an air of authenticity, however contrived it might actually be. And an uncut Facebook Live broadcast by amateurs only amplifies the “reality.”

Facebook is a fickle home for the hunters’ work. The platform will take down or suspend the pages or groups, and some have had to rebuild their followings from scratch.

Sometimes, the hunters claim, the takedowns will be a result of so-called “mass reporting,” when rival teams will have their members (or simply people who oppose their methods) flag content to Facebook. Blas says he’d been targeted by trolling campaigns and doxxing—posting his personal information online. There are videos on YouTube and even separate groups on Facebook dedicated to criticizing certain hunters. Blas kept his page down for months, worried that it would get flagged.

Weeks says he’d been ousted by his friends, administrators of the Facebook page, who booted him and shut down the entire operation after he had been caught driving under the influence.

“Facebook’s just fucking brutal,” he said. Still, he kept doing sting operations on his personal profile, and eventually restored his original page.

Modern vigilantism

The rise of the pedophile hunter groups is inextricably linked to the internet and, in its most recent iteration, to the explosion of social media. But there might also be other forces at play.

Vigilantism often bubbles up when there is a breakdown—real or perceived—of the state, of international order, of stability and security, which is certainly something we’ve seen in the early 21st century. For people who feel that their status had eroded, “it allows them to feel some sense of control and power,” Kohm said.

It helps when the state has let others in to help with the administration of criminal justice. In many countries, including the US and the UK, more non-governmental actors are involved than in the past, like private corporations that run prisons, Kohm points out. For years now, law enforcement have asked citizens to participate through so-called “community policing.”

And where people see crimes—real or perceived—going unpunished, people will take up the call.

Online, this tension becomes particularly acute. The laws governing the internet are not particularly clear, or they simply do not exist. Crime prevention measures that work in real life don’t apply online, Byrne said. Whether or not police are devoting enough resources to internet crimes, it’s easy to view their efforts as insufficient and to take matters into your own hands.

Kohm attributes vigilantism in part to the fact that in modern societies the state has a monopoly on violence. “It’s an attempt to try to reconnect with that sort of visceral, emotional, and violent impulse that over the long term, over hundreds of years has been gradually repressed and suppressed and taken over by government,” he said.

The digital vigilante operates in a nearly lawless space, weaponizing a crucial online commodity: information. Like the modern state, which has theoretically moved away from punishment of the body (torture, public execution), to punishment of the mind (incarceration, sex offender registry), vigilantes no longer use tarring and feathering as punishment. Society no longer cuts off people’s hands for their transgressions, but we do publicize their mugshots and criminal records. Similarly, the digital vigilante exacts his public humiliation simply by exposure.

“You’ll be naked but you’re going to live,” Byrne added. “I don’t know if it’s more humanizing. I don’t think so, because privacy is a core issue of the modern state.”

When Blas meets his targets, he feels “disgust and anger,” at society, the “system” that allows their behavior. “I literally wish I could rip their heads off, but I can’t.”