Are aquariums moral? It’s complicated, says Jacques Cousteau’s grandson

The ethics of aquariums are a slippery matter.

The ethics of aquariums are a slippery matter.

On the one hand, aquariums provide educational opportunities. They can teach kids and adults alike about the wonders of our oceans and the life contained within them. This awe can then hopefully be translated into action, whether that’s avoiding products containing microplastics or using turtle-killing plastic straws.

On the other hand—or flipper, or fin—they normalize the domestication of wild animals for the purpose of human entertainment. They trap creatures who normally have whole oceans to roam in environments the size of swimming pools. And in the worst circumstances, such as those widely documented at SeaWorld, they can kill the very animals they’re claiming to protect.

So how should we weigh up the pros and cons? Why not export the philosophical conundrum to someone who spends his life pondering these kinds of questions: Fabien Cousteau.

Fabien has a storied family history to draw from. His grandfather Jacques Cousteau tried to teach people to appreciate the ocean as a whole, rather than the things in it, through his television shows and films. His father Jean-Michel is an underwater film producer. And Fabien continues this familial legacy through his work today, which focuses on marine research and education.

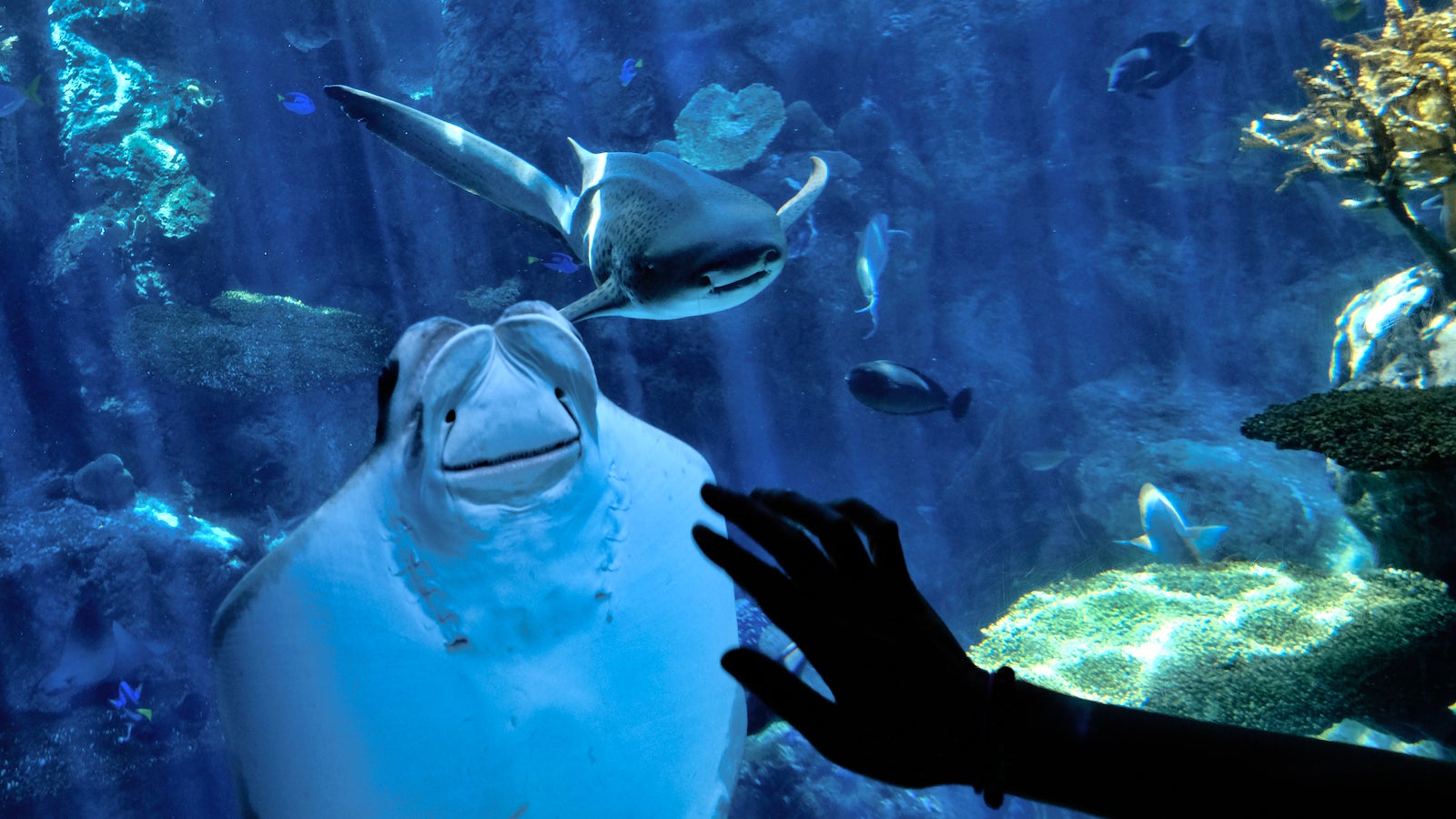

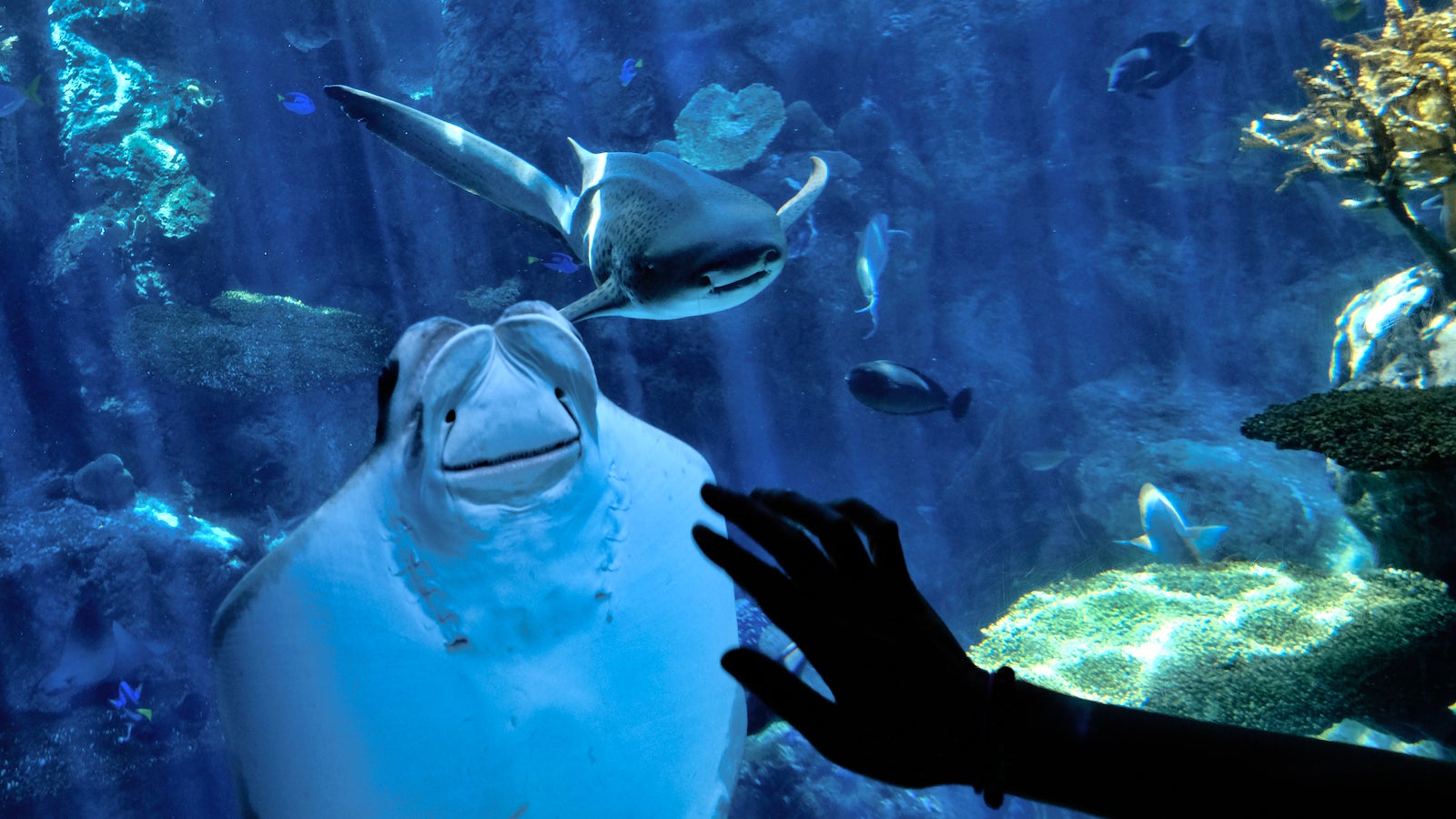

What better time to ask one of the world’s leading oceanographers about the morality of aquariums than in an aquarium? This interview took place between the otter feeding display and some rather lovely coral at the Oceanário de Lisboa during the Global Exploration Summit in Lisbon. It has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Quartz: When are aquariums moral?

Fabien Cousteau: We’ve had this philosophical struggle with aquariums for generations now: What is an aquarium? What does it mean? How does it benefit society? What are the parameters within which it can exist? And where do you draw the line?

For example, aquariums filled with captured, healthy cetaceans [such as dolphins] is a giant no. For me, anyway. But if the aquarium contains animals that were permanently injured due to human activity—such as being caught in nets, hit by boats, that sort of thing—then I feel that we have a responsibility, just like in any accident, to take care of that animal.

That animal could then become an ambassador. For example, Winter the dolphin in Clearwater Florida. Winter’s tail was chopped off unfortunately when she was very young. She could not be released into the wild. She couldn’t feed herself. Instead, she grew up in captivity, and she became an ambassador for dolphins. She allowed for people to connect with something that isn’t necessarily in their backyard.

Sharks are another animal people tend to put in aquariums. That’s a difficult call, as there are 480 species of sharks, and they all have very different territories and habitats. Can a certain species of shark be happy in an aquarium? As a human being, it’s very difficult to say what the shark thinks. Will they be happy and healthy if you give them enough space and feed them enough? I would draw the line at larger animals, like whale sharks and white sharks. They normally travel thousands and thousands of kilometers, and we’ve seen what happens when we try to keep them in captivity. So that’s not okay. Smaller sharks might be okay, providing the aquarium gives them a semblance of a happy, healthy life.

At the end of the day, the cost/benefit analysis is whether the education and value of teaching the public is serving the greater good of protecting our ocean planet. It’s a difficult one—I wouldn’t envy anyone who runs an aquarium of any sort. There are some aquariums out there that in my opinion are run much better than others.

For example, my grandfather tried to run an experiential aquarium that had no captive animals: the Parc Océanique Cousteau in Paris. It ran for over a decade. It was more of an amusement park than an aquarium. After you paid your ticket, you would get into a gondola and they would bring you through these exhibits. You’d dive into shallow waters, dive into deep waters, and see all these animals, be it virtual or puppets. Then you would get out of the gondola and walk through a kelp forest, go through some other exhibits, then eventually you would get to this big giant open room that was blue and shimmering, just like if you were under the ocean. And there would be a giant blue whale heart that you could walk through. These were all sorts of experiences that would give people a sense of what’s going on in the ocean.

Is that the solution? Yes, no, not necessarily—depending on your audience. But at the end of the day, you’re responsible for making the right choice.

How should consumers make choices about which aquariums they go to—or if they go at all?

By and large, aquariums now are trying to be based more and more on conservation messaging and education, not just entertainment. And I think that’s a big step in the right direction.

As a consumer, if you have a choice between aquariums, and if one happens to be more eco-conscious—rather than having the silly tricks with the dolphins jumping—then choose the better one. Because at the end of the day, you’re taking your kids to these places, and you’re trying to teach them the right way to think: a better way to think, a better way to be stewards of our life-support system, our aquatic planet. So if they see how they treat these animals, it’s something that will last them for the rest of their lives. We need to show them things that are the tools that will make them better citizens of the planet.

Both people on the waterfront and people in landlocked areas can greatly benefit from that experience. I think my grandfather’s aquarium was a bit ahead of its time. Nowadays, people are getting much more savvy in their understanding. All you have to do is look at this beautiful aquarium here: People are riveted with some of these exhibits. Being on an ocean, be it virtual or real, gives us a sense of tranquility and happiness. Of calm.

A philosophical question: If you could feasibly have a giant aquarium the size of the whole ocean, would it still be moral, as the animals are still being held captive?

If the aquarium was the size of the ocean, then we wouldn’t need an aquarium! We are all living in an aquarium: It’s called planet Earth—which I think actually should be called planet Ocean.

If we had an aquarium that’s large enough and is built in a way that mimics the natural ecosystem—like this coral reef in front of us, half in and half out of the water—and it’s large enough for the majority of the animals that live in that area to be there, then it is possible to do so.

But it’s also very expensive. Trying to manipulate nature is very expensive, and sometimes impossible. I’m sure behind the scenes, the infrastructure needed to just pretend that this is an actual body of water, an actual sea, and an actual beautiful coral reef would be very complex. You’d have to have the filters and the desalinizers. That, and you’d have to make the animals play nicely together! When you start thinking about it, it’s amazing that they can keep something like this going.