Could smoking bans be the new indicator of economic growth?

You might not expect Russia, the world’s second-biggest cigarette market, where 42% of the population smokes, to be thinking of limiting the vice. Yet the country is mulling “smoke-free” measures that would ban tobacco ads, boost taxes on cigarettes and prohibit smoking in public places across the country by 2015.

You might not expect Russia, the world’s second-biggest cigarette market, where 42% of the population smokes, to be thinking of limiting the vice. Yet the country is mulling “smoke-free” measures that would ban tobacco ads, boost taxes on cigarettes and prohibit smoking in public places across the country by 2015.

Public smoking bans are spreading in many emerging economies. Cigarette firms could once rely on these markets to prop up their sales, as rich countries progressively clamped down on smoking and tobacco advertising; but whereas rising cigarette sales used to be a sign that poor countries were growing, it’s now a decline in smoking that seems to be the marker of increasing prosperity.

The links between poverty and tobacco use have been under-researched. In part that’s because smoking-related problems like lung cancer and heart disease were assumed to be rich-country problems—“diseases of affluence,” says Armando Peruga of the World Health Organization, which published one of the first studies on the topic last year.

Smoking rates do grow with the economy, up to a point, Peruga says. In very poor countries with no tobacco-control policies, smoking increases with disposable incomes—and tobacco companies have focused marketing efforts there. But as as living standards and education levels continue to rise, many countries see tobacco use fall off. Peruga says that national smoking rates also dip as governments become more transparent—presumably because tobacco companies’ have less influence on tax policy and other regulations.

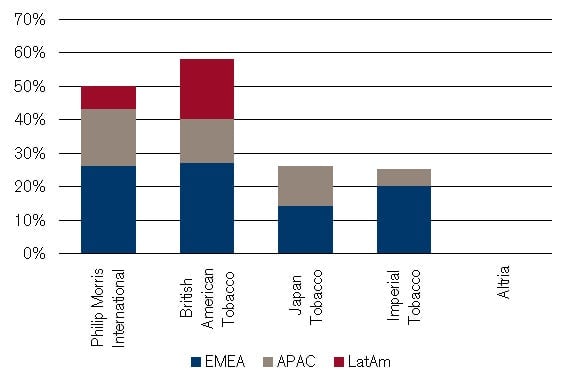

The planet is home to about 1 billion smokers, according to the WHO. Nearly 800 million are in low- and middle-income countries—an opportunity not lost on Big Tobacco. China, the world’s biggest cigarette market, is controlled by state-owned China National Tobacco Company. The rest of the world is dominated by four large companies (see chart). Two of the biggest, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco, draw at least half of their revenue from emerging economies. Philip Morris’s US-based parent, the Altria Group, in fact spun off Philip Morris in 2008 in part, critics say, so it could tap emerging markets without the interference of tighter US regulations.

That global push has not gone unnoticed. Calling tobacco “one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced,” the WHO accuses cigarette makers of exaggerating their role in creating jobs and growth, as well as of discrediting science that shows the risks of smoking. Some 6 million people a year die from tobacco use or exposure, according to the WHO, including 600,000 from second-hand smoke. As well as the human cost, that’s a huge burden on public health budgets, incomes, and productivity.

But 37 countries have prohibited smoking in public places including bars and restaurants since 2004, according to Tobacco Free Kids, a Washington-based advocacy group that tracks legislative developments; and handfuls have implemented bans on local or state levels, including Brazil, India, and South Africa. Some 59 countries monitor tobacco use with regular national surveys.

Ad bans and taxes—as well as graphic photo warnings plastered on cigarette packs—have been shown to slash smoking rates in rich and poor countries alike, according to the WHO. The 19 nations that have already banned advertising have seen tobacco use fall by an average of 7%. Tax hikes that boost cigarette prices by 10% have been shown to cut consumption by 4% in rich countries and 8% in low- and middle-income ones. According to the WHO, 27 countries tax cigarettes by at least 75%.

Russia’s anti-smoking bill won backing this week from former Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev, who slammed the tobacco industry in a video blog post. However, it’s not clear yet how far the bill will go. Medvedev, who is far less powerful than President Vladimir Putin, is known for backing reforms that end up not happening, and political scientists dismissed his antics as the latest in a series of steps he has taken to retain political relevance after swapping places with Putin earlier this year.