The world’s most famous explorers on how they handle high-stress situations

Being suspended over a molten methane gas pit. Losing visibility while free climbing a 3,000-foot cliff face. Being hit in the face with a jellyfish while deep-sea scuba diving. Having your oxygen tank explode while circling the Moon.

Being suspended over a molten methane gas pit. Losing visibility while free climbing a 3,000-foot cliff face. Being hit in the face with a jellyfish while deep-sea scuba diving. Having your oxygen tank explode while circling the Moon.

Work hazards like these put humble, Earthbound tasks like fretting over client deadlines and delayed flights into sharp relief. But these kinds of adventures are just par for the course—if that course was circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon—for members of The Explorer’s Club.

This elite organization was founded in 1904 and currently calls the likes of Buzz Aldrin and Jane Goodall among its 3,000 invitation-only guests. To qualify for nomination, you need to have done something truly earth-shattering (literally, for those members who study earthquakes). At their annual dinner this year, for example, 250 people had been to the North Pole, 150 to the South Pole, an odd dozen had summited Everest, two had been to the bottom of the Mariana Trench (the deepest point in the ocean), a bunch had orbited the Earth, and six people—six!—had been to the Moon.

Last month, the group held its inaugural Global Exploration Summit in Lisbon. It was the kind of conference where you’d overhear stories that started with “So, when we were coming back to Earth…” or, “Well, this one time when I had to call the department of defense in Madagascar…” It was the kind of party where Egyptologists taught you how to walk like an Egyptian to the song “Walk Like an Egyptian.” It was the kind of keynote where a speaker could ask the audience a normally rhetorical question—like, “When was the last time we sent a hominid into deep space?”—and someone would yell out the answer from the auditorium. (It was 1972, for future reference.)

The summit’s attendees have been to the bottom of the seafloor, the top of Earth’s tallest mountains, and even outer space. Who better to ask about their mantras for keeping calm in high-stress situations?

Here are some of their answers.

Vanessa O’Brien, mountaineer

First American/British woman to summit K2

I find rather than a mantra, per se, I count. There is a great anonymous quote that says “Mountain climbing is extended periods of intense boredom, interrupted by occasional moments of sheer terror.” This is so true, therefore focusing on what your mind does becomes critical to success. That should encompass both razor-sharp concentration to spot any obstacles (like crevasses and avalanches) and distractions (to stop you from thinking how miserable you are). Counting is great because you can do this without thinking—that’s the key. I like singing “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall,” which takes ages.

You also need to turn around negative thoughts, as these will visit you the more knackered you are. Thoughts are clever—they play on emotion. They can appeal to your common sense by reminding you to cut your losses and turn around, to your pride by telling you that don’t need to prove anything to anyone, or your sense of self-preservation by reminding you how tired, hungry, cold, and thirsty you are. I like the visual of putting negative thoughts on a raft and floating them down a river. You could also visualize an angel on one shoulder and the devil on another—just be careful to know which is which if you start speaking to one!

As someone who specializes in documenting extreme forces of nature—tornadoes, hurricanes, volcanoes et cetera—I frequently find myself in high-stress situations that can be genuinely life threatening.

There was an instance when I was about to step off the edge of crater into a flaming pit of methane gas in the Turkmenistan desert that is nicknamed the “Doorway To Hell.” I was roped in and harnessed up, and wearing a special heat-resistant suit. This was something that no one had ever done before, and despite the research, the equipment, and the great team I had with me, it all came down to that one moment when I had to surrender all control and step off, putting all my weight onto the ropes and dangle 100 feet above the fire. Right before stepping into the flaming void, I whispered to myself, “You can do this.”

Felicity Aston, skier

First woman to cross the Antarctic landmass alone

While skiing across Antarctica by myself, I would wake up every morning of the expedition in my tiny tent to the sound of the wind whining across the vastness of the Antarctic plateau outside, and the very first thought that would fire through my brain would be “I can’t do this.”

I knew, with solid conviction, that I was not the person to succeed. Finding the motivation each and every morning to get out of the tent and attempt another day—despite my conviction to the contrary—became the biggest challenge of the expedition. My most sacred mantra now, whatever I am facing, is “Just keep getting out of the tent.”

James Moore, planetary geologist

First person to measure the strength of the Earth’s crust—and Mars’s—from space

I find just the knowledge that I’m in a high-stress, risky, or dangerous situation can focus the mind greatly. It’s almost peaceful or serene in some ways, because the stray thoughts quiet down as my focus shifts to dealing with the immediate situation, and that comes with a heightened awareness of my surroundings. I lean in to the terror.

For example, I remember a time a few years ago when I was scaling Scafell Pike with a friend. A bank of fog suddenly rolled in when were most of the way up a cliff face. Visibility suddenly and unexpectedly dropped to 3-4 feet—and did I mention that we were free climbing? Thankfully we were only 20-30 feet from the path we would be joining at the top of the cliff, but progress slowed to a crawl. My primary concern in high-stress situations like those then turns to keeping track of fellow team members—or the students! I took some of my PhD students out to Krakatoa when it was erupting before, so they were definitely worth keeping an eye on.

Louis-Philippe Loncke, explorer

First to cross the length of the Simpson desert by foot

If I’m in danger or a life-threatening situation, my main thought is not wanting to fail the expedition—or not wanting to die. Those situations are different to the other type of “stress,” such as if I’m in no danger but need to push hard to reach a point I want to reach that day, whether it’s a nice view before a sunset or a reaching a camping spot by a lake or stream where I don’t have to worry about water.

In the dangerous situations, the motivation I give to myself is shorter, as I don’t need to sustain it to progress—you’re dealing with an immediate stressor. My metabolism might raise, and my body will get stronger, less prone to pain, and will not care if it’s dark or not. Actually, the dark can be a good place to be in danger! Because your focus has to be extremely high and you also see less danger (as it’s dark), so you can focus on progress while being in a heightened mental state. Our determination might even become so high that we think we’re invincible, which is very dangerous. If that happens, we neglect the messages of the body and lose focus. We can end up trapped in our beliefs, and this is where an accident can happen, tricked by our brain.

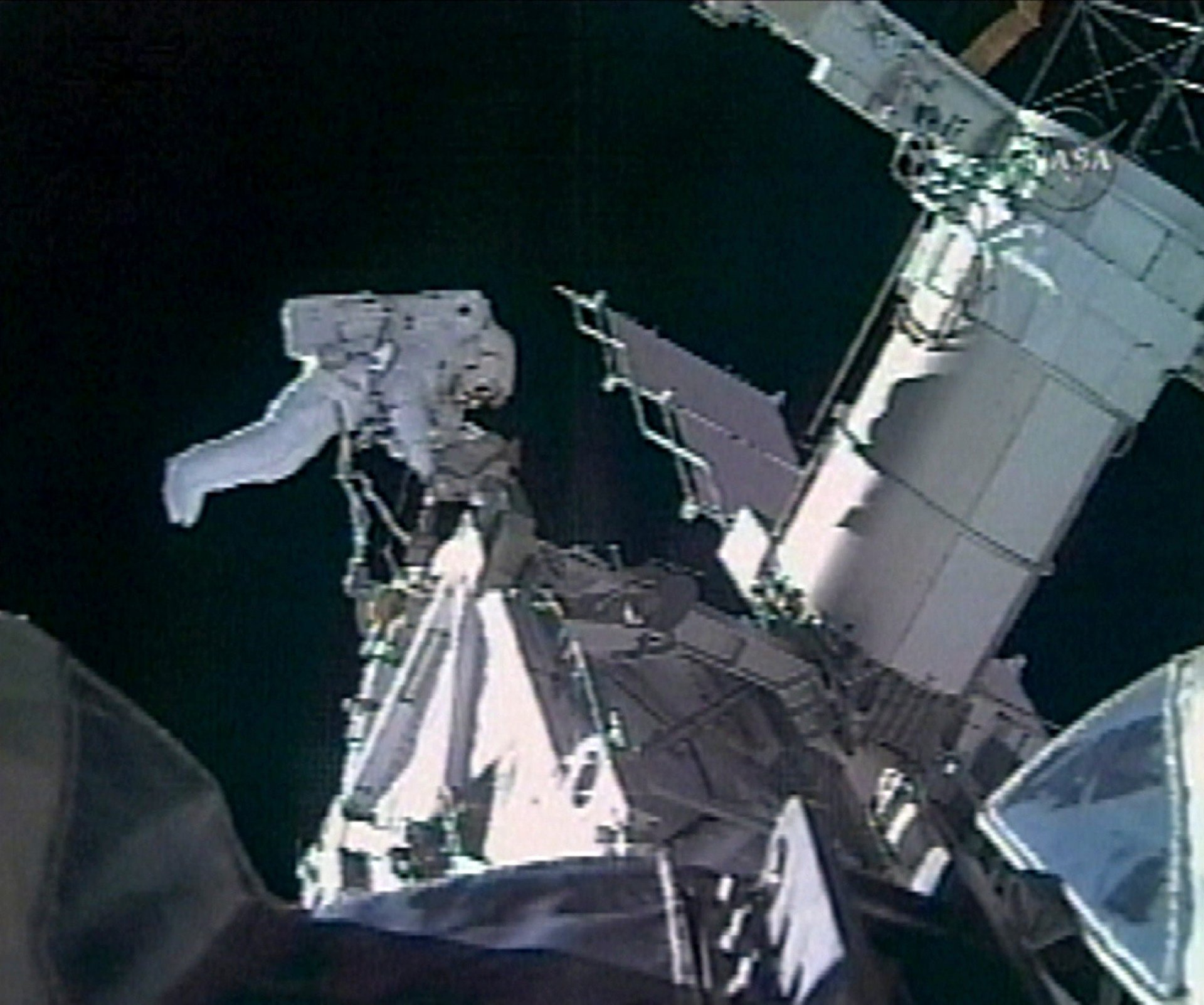

Dafydd (Dave) Williams, astronaut

Completed the most spacewalks an astronaut has performed in a single mission

Throughout my career I’ve had a number of challenges as well as successes. Whenever I face adversity, I try and focus on the problem and work at finding the best possible solution, pursue that solution, and regroup as necessary.

The best example of this wasn’t in space, but on Earth. At age 50 I was diagnosed with cancer and lost my astronaut/pilot medical status. After complex surgery and five days in the hospital, I started the rehabilitation journey to try and get my medical status reinstated. It was a six-week journey of gradual progress, each day focusing on what needed to be done without worrying about what tomorrow might bring. Around two months after the surgery, I was medically recertified for spaceflight and flew in space three years later as cancer survivor.

Beverly Goodman, marine geoarchaeologist

Discovered 65-million-year-old tsunami deposits from meteorite impact

During work projects we often spend long hours underwater performing a sequence of tasks, like drilling and removing cores or excavating archaeological areas. Despite the fact we plan for months in advance and practice over and over, sometimes things don’t go exactly as planned. You therefore have to be ready to both make good decisions to resolve the problem and also balance that with completing the mission and staying safe.

In most stressful diving situations, the greatest enemy is panic. Panic can lead to bad decision-making, increased air consumption, and tunnel vision. One of my habits to stay calm is to run through a series of checks: How much air is in each tank? What are my oxygen levels? How long have I been underwater? What is the depth? I have a little checklist in my head that I run through every 10 minutes or so that becomes like a ritual. It also helps ground me and prevents me from getting too lost in an activity.

For example, we once had an unexpected visit from a four-meter-long tiger shark while we were collecting samples at about 45m water depth in a place where we had only one chance to take the samples. Because it was a decompression dive, we could not easily shorten the dive. My reaction was to remind myself to remain calm, control my breathing, and stay close to the heavy equipment in case I needed to give the shark a bump on the nose with something hard!

During another dive, a large jellyfish ran into my face in relatively deep depth. (Yes, I should have seen it coming, but I was a little preoccupied.) But I couldn’t exit the water for another 20 minutes. So I relaxed, did breathing exercises, and sung little happy songs to myself until it was time to surface.

Liv Arnesen, skier

First woman to ski solo to the South pole

I do not have a special mantra, but in particularly stressful and dangerous situations like skiing on a glacier with many cracks, being close to losing my grip climbing, or when there’s a polar bear nearby, I focus on my breath: Quiet breathing, and exhale. I get a sense of control doing that.

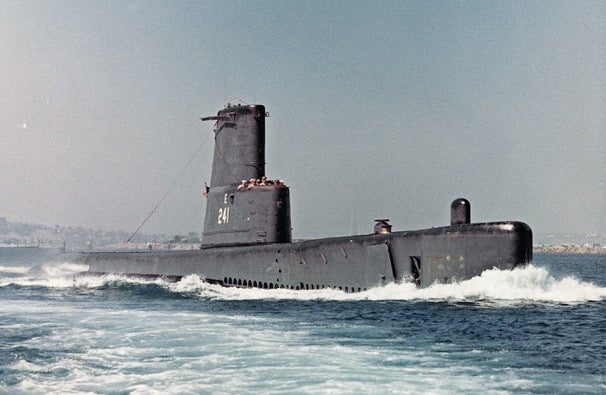

Don Walsh, submarine oceanographer

First (with Jacques Piccard) to reach the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest point in the ocean

During my 24 years of being in the Navy, 14 of it in submarines, I got the training and learned the discipline about how to handle emergency events. Fear or indecision can be fatal; clear thinking is absolutely essential when a situation arises. In submarines, you have to act fast to avoid loss of life—or the ship itself. You learn to supervise remedial actions but not get hypnotized by the immediate emergency. That’s because casualty situations often cascade, and additional problems may arise concurrently. Situational awareness is paramount.

In aviation, the first rule of handling an emergency is to “fly the airplane.” It’s simple, but it’s what I used to do at sea.