Saudi Arabia strives to get more citizens on private payrolls, one lingerie shop at a time

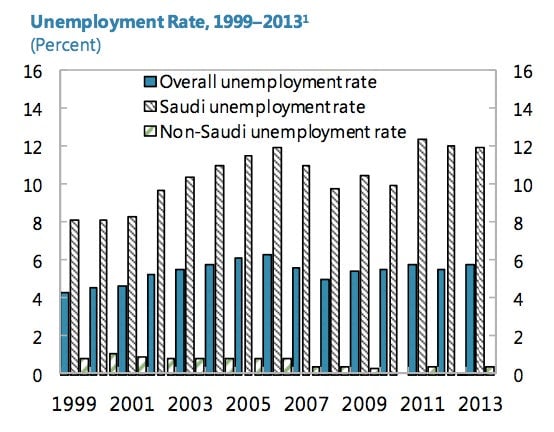

Saudi Arabia’s labor market is a mess. Despite a headline unemployment rate of 12%, only an estimated 30 to 40% of working-age Saudis are employed or seeking work. Among this group there is a strong preference for undemanding, high-paying government jobs instead of private-sector positions, the majority of which are filled by foreigners.

Saudi Arabia’s labor market is a mess. Despite a headline unemployment rate of 12%, only an estimated 30 to 40% of working-age Saudis are employed or seeking work. Among this group there is a strong preference for undemanding, high-paying government jobs instead of private-sector positions, the majority of which are filled by foreigners.

The Saudi government is well aware of the problem, which could reach crisis levels as the country’s population expands. It has announced common-sense measures like unemployment insurance to encourage workers to take a chance on a private-sector job, creating a safety net if the company cuts back or goes under. It has also imposed harsher measures like a crackdown on undocumented foreign workers and a stricter enforcement of quotas on hiring Saudi citizens.

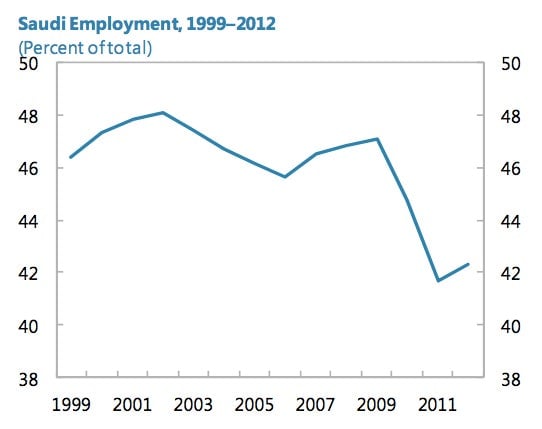

Labour Minister Adel al-Fakeih said on Jan. 19 that the country has doubled the number of Saudis working for private companies, to about 1.5 million, since it began reforming the labor market two and a half years ago. Yet the IMF reports that 1.5 million of the 2 million new jobs created in the last four years went to non-Saudis.

Those woes don’t even take into account the extreme dearth of jobs available for educated Saudi women, thanks to the kingdom’s strict religious laws against women having contact with any men beyond their immediate family or driving unaccompanied by a male relative. ”Right now, we have a labor market for men, and a (separate) labor market for women,” Thuraya Obaid, a former UN official who is now an appointed member of the country’s advisory legislature, said at a conference on Jan. 19.

The Saudi government has tried to boost female employment by allowing women to serve female customers, most notably in lingerie shops, where women have long complained about inappropriate attention from salesmen. These reforms caused an uproar from Saudi religious authorities—as the New Yorker reported, conservative clerics threatened to pray for minister al-Fakeigh to get cancer unless he revoked the decision to let women work in retail. When women and men both work in a department store, partitions must be erected at least five feet tall so that women won’t have any contact with their opposite-sex coworkers.

But the lingerie shop reforms haven’t always had the intended effect, with many shops reportedly forced to close because not enough Saudi women were available to fill the necessary jobs. Businesses are now clamoring for expat women to be allowed to fill these and other private sector jobs, including health, education, dressmaking, childcare, and housecleaning. The labor ministry released a draft plan that would allow those hires in December.