Students in Hong Kong used fax machines to fight Chinese censorship of Tiananmen Square

In 1989, when the spring met summer, most people in Hong Kong, no matter how ordinary they were, became a part of a once-in-a-lifetime, mind-blowing moment.

In 1989, when the spring met summer, most people in Hong Kong, no matter how ordinary they were, became a part of a once-in-a-lifetime, mind-blowing moment.

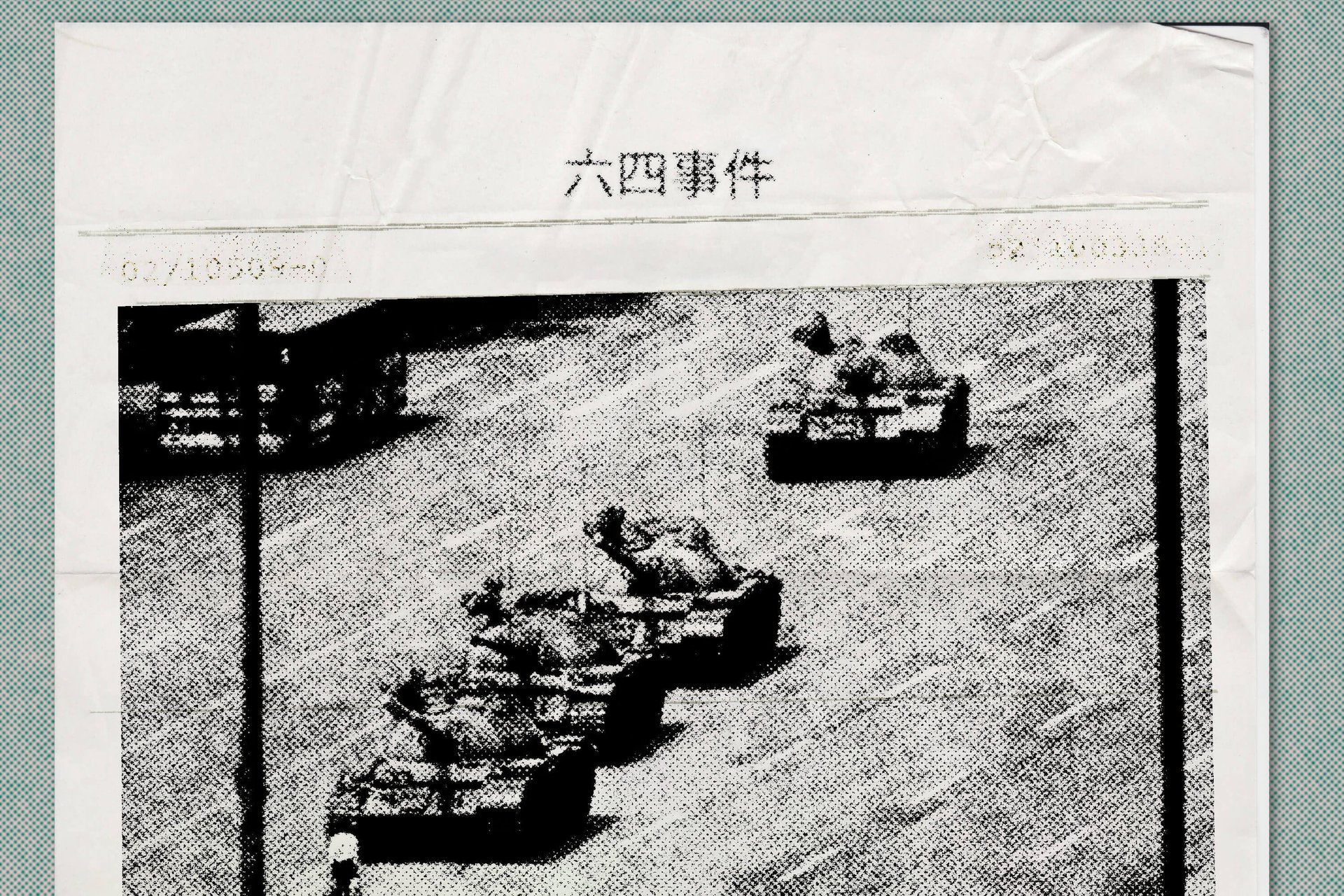

On April 15, Hu Yaobang, a leader widely known as a key reformer in post-Mao China and who had been sacked by the Chinese Communist Party two years earlier, died at the age of 73. In a moment defined by widespread inflation, corrupt bureaucracy, and the aftermath of an unsuccessful student movement, the former liberal leader’s death reminded citizens that these grievances remained unanswered. Hu’s death triggered a series of commemorations, student demonstrations, rallies, and occupations of one of China’s political and cultural landmarks, Tiananmen Square in Beijing. On May 19, the government issued martial law, sending troops and tanks to the Square and the surrounding regions. The suppression culminated in the Tiananmen massacre on June 4, 1989.

At the time, most Chinese outside of Beijing didn’t know much about what was going on. The government censored information about the uprising, preventing missives from being published in newspapers or broadcast on the news. Now, 30 years after the events at Tiananmen Square, most people in China still know little about this history—despite the ubiquitousness of the internet in China. The reason? China’s infamous internet censorship system, the innovation that has earned the country the dubious accolade of “the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom,” according to US-based think tank Freedom House.

At the time of Hu’s death, I was an ordinary freshman studying at The University of Hong Kong. I was having a fairly standard college experience, one that removed me from the “real world”—the university’s off-campus dormitory, called University Hall, is literally a castle. On that April 15, most students had locked themselves inside their dorm room or stayed in the library to prepare for exams. Every desk on the campus was quiet.

Soon, though, that would change. In the days after Hu’s death, even in Hong Kong, nearly 2,000 km from Beijing, most HongKongers were touched by the spirit of the Beijing movement and obsessively followed the news on live television and newspaper. This was in stark contrast to people in China, who had no information on the Beijing movement because all Chinese, party-controlled media outlets were not permitted to release any news about the protests.

My classmates and I wanted to make a difference. Instead of organizing a rally or an assembly, as other HongKongers did, we decided to break the news blockade. We turned to one of the most advanced communications technologies at the time: the fax machine.

Our plan was simple but ambitious: create a daily news digest about what was happening in Beijing; obtain the list of every fax number in the country that was printed in the Yellow Pages; send the digest out to all of these fax machines.

To get enough fax machines to accomplish this, we did what is now called crowdsourcing. In pre-internet 1989, we used phone-in talk shows and newspaper stories to recruit Hong Kong companies with underused fax machines. We managed to get a pool of more than 500 corporate partners to join the crowd-faxing campaign. We eventually even got some second-hand machines to use in our college dormitory. I’m not sure how many digests we sent total, or people we reached, but we did occasionally receive feedback from China via the fax machines. Some were messages of thankful appreciation and a couple of angry complaints about our “fake news.” The Chinese government, if it knew, made no effort to shut us down.

Sadly, even 30 years after our efforts, the Chinese government has only tightened its grip on the information its citizens can access. Censorship has extended from radio, newspapers, and television to the internet, which reaches almost 60% of the country’s population. Most Chinese can only access restricted information, but they don’t even know what information they are not able to obtain.

Elsewhere in the world, a search for “1989 Tiananmen Square” in Google returns news from Western sources like BBC, CNN, and the Guardian, as well as official Chinese propaganda, offering a “marketplace” of perspectives. But unfortunately, this variety is not accessible in China. Type the same phrase into Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, and you will only get hits from official party media sources that mostly describe the 1989 student movement as a “riot” and support the government’s crackdown. Also missing is access to other online platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, and Wikipedia that foster healthy debates and skepticism. Some tech-savvy Chinese netizens can use a VPN to access the internet from the rest of the world, but most people are not interested in seeking external sources of political information.

In the 2019 World Press Freedom Index, China is ranked 177 out of 180 countries. Since Xi Jinping began his presidency in 2013, taking up the head role of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, the government body responsible for online censorship, the Chinese government has been slowly tightening the control over the media.

Censorship in China is, of course, not just limited to its historical controversies—it’s actively suppressing news about today’s events, from the 2018 constitutional change to remove Xi Jinping’s term limit, to the Me Too movement. It has also extended to other media such as movies, reality television shows, pop music, and even online games.

I’ve made studying censorship my life’s work in Hong Kong, a region that is technically part of China but is governed semi-autonomously, allowing its citizens more freedom than they would be allowed in mainland China. This division is at the heart of the city’s recent large-scale protests against an extradition law that would allow the government to transfer accused criminals from Hong Kong to mainland China, where penalties are much harsher.

In my role as a professor at the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong, I study Chinese social media and the country’s digital control strategy. In 2010, we designed a system called Weiboscope, to track censored comments and posts on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter. Weiboscope works like an army of robots to keep browsing a list of tweets from more than 100,000 influential Weibo accounts to see if any post is published but then disappears. When it finds a censored post, Weiboscope redistributes it on our designated website and on social media to alert the public.

In the nine years it’s been in operation in Hong Kong, the crowd-browsing project has collected over 810 million Weibo posts, more than 700,000 of which are confirmed to be censored material (searching for them returns a “permission denied” message).

Over time, and especially in light of the 30th anniversary of the events in June, Chinese netizens are posting about the massacre on Weibo. Often, they simply offer thoughts about the incident or to commemorate those who died in the crackdown. As you might expect, the censorship authorities quickly remove these posts. But if these posts stay live for long enough, Weiboscope makes a copy and keeps it in our database. Weiboscope has identified more than 1,200 censored posts between 2012 and 2018. We also post them on Instagram, Pinterest, and the Weiboscope website.

Here are some examples: pictures with a kid riding a tank toy in Tiananmen Square, a candle light, a tankman graffiti, and a poker hand of “8”, “9”, “6”, and “4” were utterly removed by China’s Internet censorship system.

Why do people write posts knowing that they will surely be deleted? It’s hard to know for sure, but I believe that quite a number of Chinese strongly disagree with the government’s crackdown on the 1989 student’s peaceful movement, and the later official talking point of calling it “riot.” They may disagree so strongly, in fact, that they accept a certain level of risk—consequences for disagreeing with the government could include account suspension, being interrogated by the police (colloquially, being invited to “drink tea”), being sent to a detention center (this is rare but does happen to high-profile dissenters), or even sentenced to prison time. They risk all of this to be able to share their opinions with others, or to simply educate the public, since many youngsters have no idea why June 4th is significant and who the “Tankman” is. They want to show other dissenters that they are not alone.

I don’t see any signs that the Chinese government will loosen its internet censorship in the foreseeable future, particularly while Xi is in power. But as a person living with greater freedom in Hong Kong, I am obliged to continue the anti-censorship projects. I work to offer the world another perspective on China and to make the country’s internet control system more transparent, just as I have done for the past 30 years.