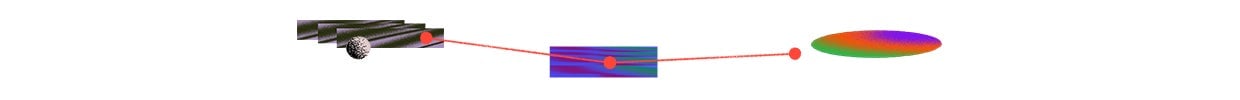

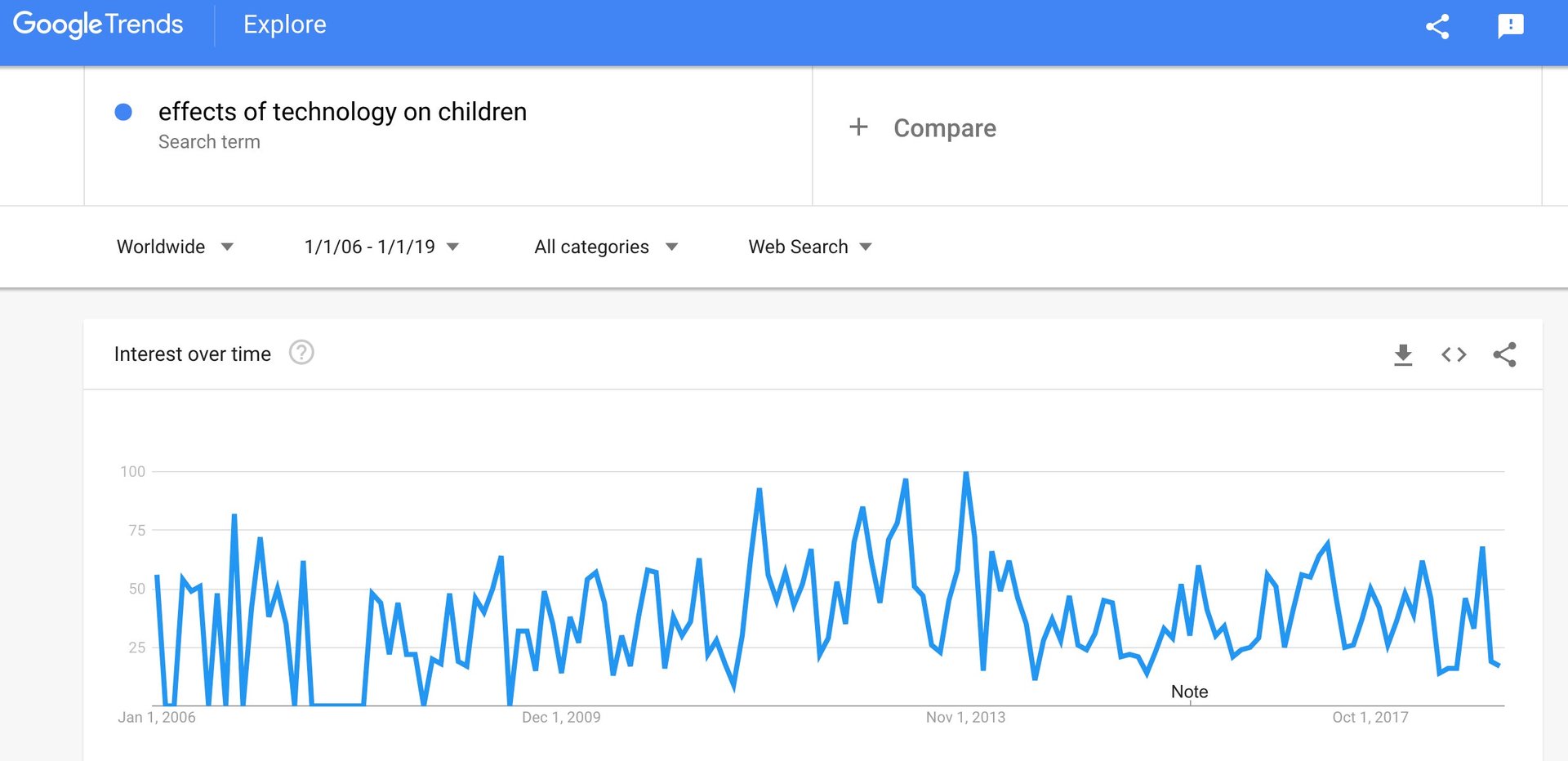

Even experts can’t agree on whether technology is dangerous for kids

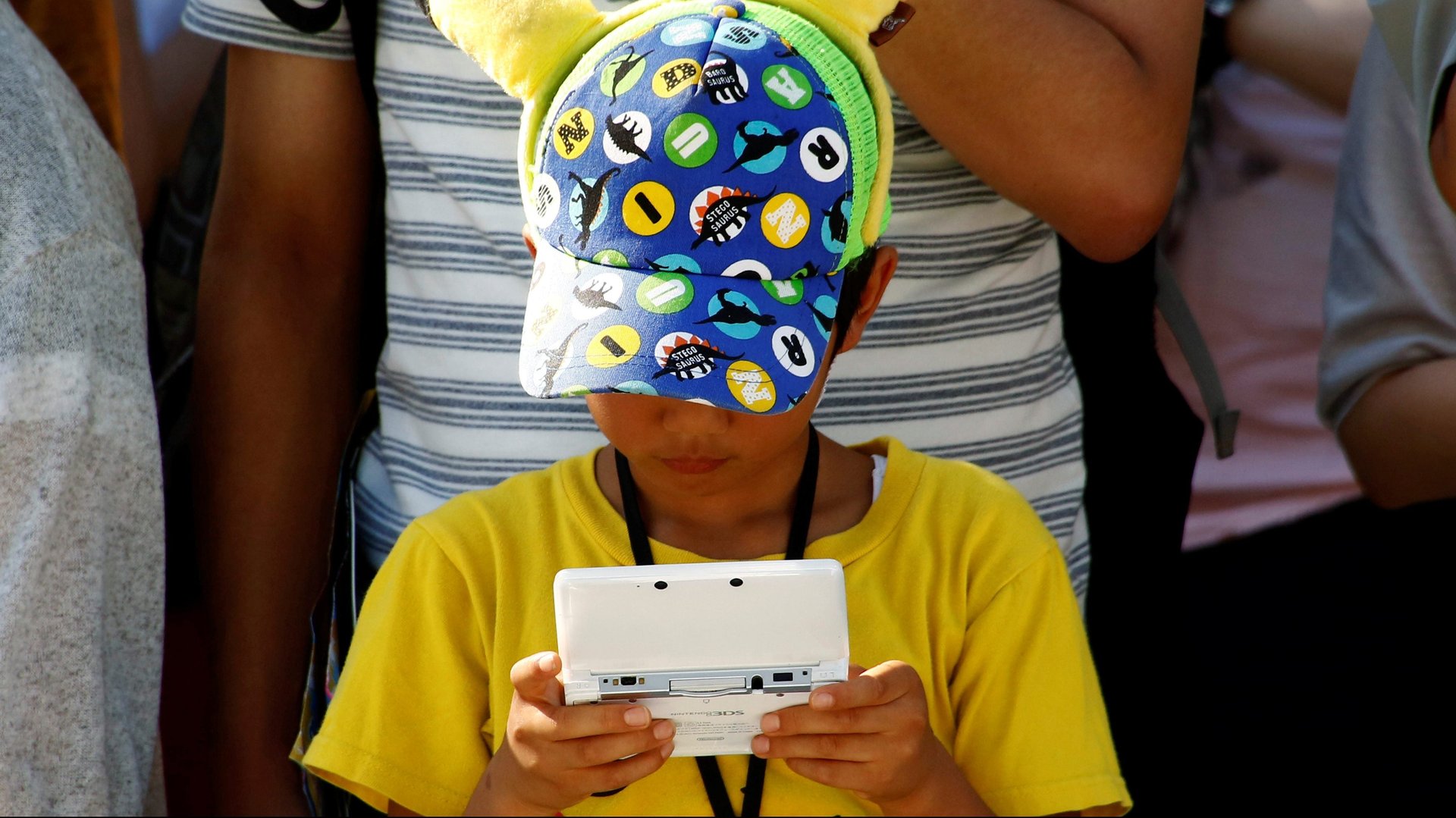

Technology developed over the past two decades—including smartphones, laptops, tablets, and the applications that populate them—has radically transformed what childhood looks and feels like, and parents are having a hard time adjusting.

Technology developed over the past two decades—including smartphones, laptops, tablets, and the applications that populate them—has radically transformed what childhood looks and feels like, and parents are having a hard time adjusting.

Not only is technology unfamiliar territory for many adults who didn’t grow up online, but the experts they are supposed to be able to turn to for answers don’t agree about what tech is doing to kids’ brains, relationships, and mental health.

The impact of tech on children

The truth is that we don’t yet fully understand the effect that living, learning, loving, and making friends in a digital world is having on children. “There is a lot of discrepancy, and it’s not exactly clear because this is all brand-new,” says Adam Pletter, a child psychologist and founder of iParent 101. “We don’t have the data, and we don’t know exactly what the outcomes are.” But he thinks that “we can make lots of good guesses.” Much of the available science on these questions centers around teens and tweens, who are more likely than younger children to own a smartphone, since about 45% of American kids get a smartphone service plan between 10 and 12.

One of the foremost experts on the impact of tech on teens is Jean Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego University and the author of books and articles about this issue. She coined the term “iGen” to refer to kids born between 1995 and 2012, who have grown up with smartphones and the Internet. Twenge writes in the Atlantic that the arrival of the smartphone in 2007 “radically changed every aspect” of iGens’ lives, “from the nature of their social interactions to their mental health.” Studies show that connected teens are less likely to engage in a whole host of behaviors their tech-free predecessors did a lot of, like date, have sex, see friends, and drive cars. Excessive screen time in children has been associated with everything from developmental delays to behavior problems and learning disabilities—though it’s important to note that many of the studies showing these links document correlation, not causation.

There also seem to be ways in which constant use of technology makes teens and tweens both more and less safe. Most parents who choose to give kids under 13 a smartphone do so for security reasons: The devices allow parents to get ahold of their children or even track their location, and data does show that iGens might be safer IRL (in real life) thanks to technology. According to Twenge, they are less likely to do reckless things like get pregnant as a teenager or binge drink. “More comfortable in their bedrooms than in a car or at a party,” Twenge writes, “today’s teens are physically safer than teens have ever been.”

And yet, as Twenge told Quartz, iGens “may be physically safe that way, but mental health is a whole other question.” There are worrying signs that teens’ use of social media networks like Facebook and Snapchat is contributing to a mental health crisis in their age group. Phones also seem to be getting in the way of sleep, which has been directly linked to later emotional issues in teens. According to Twenge’s research, between 2008 and 2017, depression, self-harm, and suicide rates jumped in teenagers and young adults. She attributes this shift to smartphones and digital media, and the impact they have on kids’ social and emotional lives.

Beyond the mental health and cognitive impacts, there are also very real dangers online: While iGens are up in their bedrooms, on their phones or laptops, not drinking or partying, they could be hanging out on Houseparty, an app that allows them to join a virtual “party” by video-chatting groups of people, including total strangers trolling around the Internet for access to minors. They could be exposed to violent and offensive language on Discord, a chat room for gamers, for example, or watching hours on end of conspiracy videos on YouTube.

Parents who might be reading this and feeling inclined to make their kids delete all their apps should know that, even on these questions, experts disagree. Psychiatrist Richard Friedman wrote that “there is little evidence of an epidemic of anxiety disorders in teenagers,” and that the evidence that does exist mostly relies on parents or kids self-reporting their own feelings or their kids’ feelings. Those surveys “tend to overestimate the rates of disorders because they detect mild symptoms, not clinically significant syndromes,” he writes. He speculates that the so-called teen anxiety epidemic “is simply a myth.”

Many other experts note that anti-screen hysteria is not always justified. They say screens and the internet, like anything else, should be used in moderation; in excess, they can harm more than they help. “When children use technology,” read a recent New York Times headline, “let common sense prevail.”

Meanwhile, Jordan Shapiro, an assistant professor of philosophy at Temple University and author of The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World, argues that, while “there’s a lot of fear about the terrible things that happen online… there’s not a lot of data showing it.” And it’s true that research shows that the perceived prevalence of risks like sexual harassment and bullying online is often overblown.

Even if there is cause for concern on that front, some say that trying to monitor everything kids do online, or keeping kids away from technology altogether, could impede their ability to deal with the challenges of online life in the future. “At some point, your child has got to learn to stand on their own two feet online, because they are going to be an adult in that weird and wonderful and horrible world,” says Sonia Livingstone, a professor of social psychology at the London School of Economics who specializes in digital media and kids. “And you can’t protect them until they’re 18 and then have them be a resilient person who can make decisions themselves.”

Parents find themselves having to balance all of these considerations while dealing with the immediate challenge of a tween demanding an iPhone because everyone else in their class has one, or a teenager hiding a secret TikTok account. They know that, no matter what they decide, they’re sacrificing something—like their kids’ privacy at the expense of their security, or their future digital literacy in the name of protecting their childhood.

Tech anxiety among parents is palpable. Athena Chavarria, an executive assistant to the CFO at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, memorably told the New York Times: “I am convinced the devil lives in our phones and is wreaking havoc on our children.”

How parents are adapting to these new challenges

To a certain extent, some of the parenting challenges of technology can feel like repackaging old problems. Bullying, teenage mental health issues, conspiracy theories, and sexual predators all existed IRL before they existed online. And in fact, according to Pew, US parents are pretty evenly split on whether the challenges faced by today’s teens are all that different: In a recent survey, 48% of parents said that today’s teens “have to deal with a completely different set of issues” than they did, compared to 51% who said that “despite some differences, the issues young people deal with today are not that different from when they themselves were teenagers.”

What’s new, according to Pletter, is the wide knowledge gulf that now exists between what he calls “digital immigrants”—Gen X parents who grew up without the Internet—and their digitally native children. So, yes, “parenting is still parenting,” he says—we haven’t totally reinvented the wheel. “But with the digital world, it has gotten exponentially more confusing and difficult to manage.”

Parents have come up with different ways to deal with these challenges. One is by scrutinizing what their kids do online. According to Pew, 60% of US parents of teens between 13 and 17 say they have checked their children’s social media profiles and browser history, and 48% say they have read their kids’ phone call records or text messages. Some parents purchase apps or software that track everything their kids write or search for online, like Bark, a monitoring software that scans children’s communications and alerts parents if it flags content related to threats like cyber-bullying, sexual content, or drug and alcohol use. (The company says it scans the phones of more than 3.5 million kids in the United States.)

If knowledge is power, then knowing what kids do and say on their phones is the key to modern parenting. But these tools raise thorny questions about privacy, children’s rights, and the limits of parents’ ability to protect their children from the very tools meant to help them navigate this information-overloaded age. And here again, experts disagree. Twenge is all for them when kids younger than 13 have a smartphone. But Livingstone says that monitoring kids’ phones at any age “sets up that model that you don’t trust your child, you don’t trust your child’s friends, and your child has no right to privacy. Your child is a kind of extension of your property.”

Other parents turn to less controversial solutions. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that parents and kids sit down to build a “family media plan” based on every family’s values and goals. Some parents write phone contracts for their teens. In fact, if there’s one thing that virtually every expert agrees on, it’s that creating rules surrounding tech use is a good thing—they just don’t all agree on what those rules should be. Some parents structure their teens’ downtime to help them unplug, but that requires spare time and resources that many parents just don’t have.

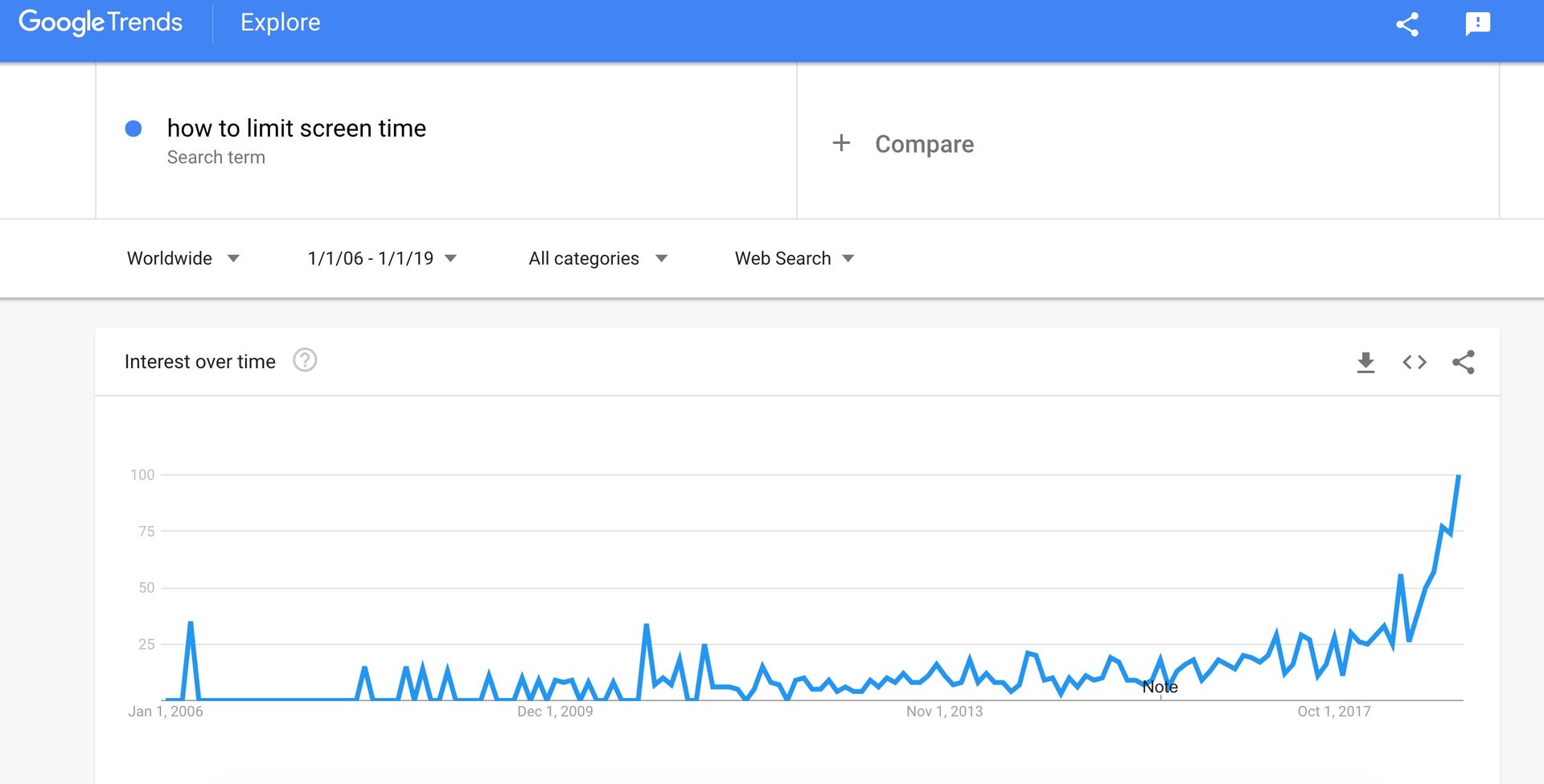

There are also plenty of tools (pdf) that allow parents to limit their kids’ screen time. But it’s not just kids that need to limit their tech use; parents are also in danger of letting screens get in the way of their relationship with their children, especially younger ones. There’s even a word for this: technoference. As Erika Christakis writes in the Atlantic, parents’ use of screens is leading to distracted parenting and poses a risk to children. “More than screen-obsessed young children,” she writes, “we should be concerned about tuned-out parents.” When parents are absorbed in email or Facebook, the quality of their engagement with their kids goes down, as does their ability to be emotionally attuned to their kids’ needs. That, in turn, hurts kids’ cognitive and socio-emotional development.

And at the end of the day, kids learn by example, so having a healthy relationship with technology is probably one of the best ways to raise kids who will model those behaviors.

For the busy and worry-prone among us, severely limiting the time kids spend on their phones and on social media—or refusing to let them have either until a certain age—can seem like the safest option. That’s more or less where Twenge falls on the spectrum of expert opinions on this question. She says she is “a big believer in waiting as long as possible to get your kids a smartphone and let them go on social media.” While every family’s needs are different, she says “middle school kids are not ready for those things.” If parents do choose to give their tweens phones or laptops, then she recommends putting limits on their social media use and monitoring what they do online.

But anyone who has been around a typical tween today knows even Iron Man couldn’t keep them away from screens or social media—that is, provided they don’t smuggle burner phones into the house (paywall) or create finstas to hide their real social media content from their parents. So “most parents fall into the middle category,” says Twenge. “They do give their kids phones because everybody’s doing it, and they let their kids be on social media because everybody else is doing it, but then they worry about what their kids are doing online and how much time they’re spending on their phones—and they don’t know what to do about it.”

Shapiro, who argues kids should use more technology, not less, says kids should start using devices even younger than they do now, while there’s still time for parents to guide them to a healthier relationship with technology. “Your job as a parent is not to stop unfamiliar tools from disrupting your nostalgic image of the ideal childhood,” he writes in his book, “nor to preserve the impeccable tidiness of the Victorian era’s home/work split. Instead, it’s to prepare your kids to live in an ethical, meaningful and fulfilled life in an ever-changing world.” To do this, he emphasizes parental engagement in kids’ tech lives. Does your child want to play video games? Great, play with them!

There are plenty of issues with this line of thinking, as Quartz’s Jenny Anderson has laid out, but one thing is undeniable, according to Shapiro: “It’s too late; we already accepted the screens.” Now the key is to help kids navigate this new medium through which they see the world and engage with it. No matter where parents stand on the question of how to best do this, it’s clear they need to decide. Says Shapiro: “We certainly need to figure it out, because it’s changing everything.”