What we can learn from the spy satellite image Trump tweeted

An Iranian satellite launch gone wrong prompted Donald Trump to gloat on Twitter—and share an unprecedented example of US spy satellites at work.

An Iranian satellite launch gone wrong prompted Donald Trump to gloat on Twitter—and share an unprecedented example of US spy satellites at work.

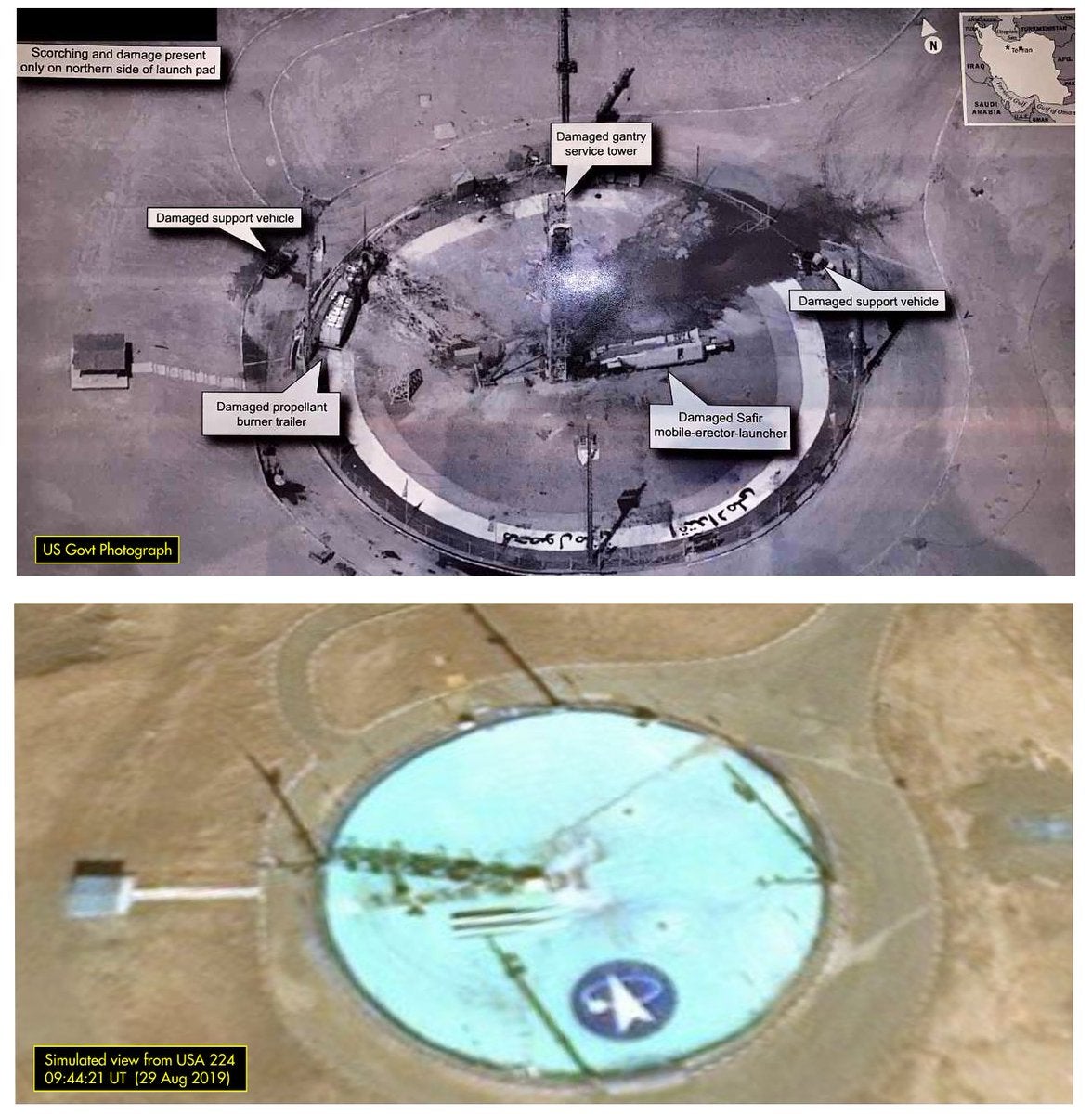

An anomaly at an Iranian launchpad on Aug. 29 during an attempted satellite launch left the site smoking. Iran’s attempts to build a functioning space program are controversial because there are overlaps between space-launch and missile technology; this is the second time this year an attempt to place a satellite in orbit has gone wrong.

The next day, the US president tweeted an image of the launch site after the accident, referencing reports that the US has attempted to sabotage the program:

Space surveillance experts and intelligence followers immediately noted the image, which is of unusual quality for orbital surveillance. Some even suspected that it might have been produced by a drone or aircraft. But amateur satellite trackers were able to analyze the image and deduce that it was taken by an American reconnaissance satellite known only as USA 224.

“I simply did not expect Trump to release a satellite image at that resolution,” Jeffrey Lewis, who directs arms control research at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, tweeted.

Dr. Marco Langbroek, a Dutch archaeologist who tracks space objects, was able to simulate the view USA 224 had of the launch site at the time the image was taken. Sure enough, they closely match—and reveal the difference between commercial and government imagery.

High-quality US satellite imagery is rarely released publicly; knowing how well these satellites can see could make it easier for adversaries to hide sensitive activities. There is also value in strategic uncertainty about just how well American spies can see into other countries’ backyards.

“The significance is demonstrating just how good US overhead intelligence is,” says Brian Weeden, a space surveillance expert at the Secure World Foundation. “A lot of us on the outside had our suspicions, but in many ways this goes well beyond what most had assumed. I was surprised at the clarity and detail. We now have a better idea of what people say when they talk about ‘exquisite’ intelligence sources.”

The resolution of the image shared by the president is estimated at about 10 centimeters per pixel; in comparison, the newest commercial satellites offer customers imagery with a resolution ranging from 30 centimeters to just below one meter per pixel. Of course, those companies aren’t spending the $2 billion or more that it costs the Pentagon to build and launch USA 224 in 2011.

Imagery from these highly sensitive spacecraft is rarely shared. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, low-resolution satellite imagery was occasionally used to brief reporters about military action in the Middle East. The last satellite system to have its imagery declassified was called Hexagon and operated in the 1970s; its work wasn’t shared publicly (pdf) until 2011.

Presidents have unilateral authority to declassify secret government information, but former members of the intelligence community criticized the president for releasing the image without redacting more of the information included or using a lower-quality version. Still, other satellite imagery experts suggested there is little that US adversaries could learn from the release, given the rapidly closing gap between publicly and privately obtained imagery.