Real-time maps warn Hong Kong protesters of water cannons and riot police

The “Be Water” nature of Hong Kong’s protests means that crowds move quickly and spread across the city. They might stage a protest in the central business district one weekend, then industrial neighborhoods and far-flung suburban towns the next. And a lot is happening at any one time at each protest. One of the key difficulties for protesters is to figure out what’s happening in the crowded, fast-changing, and often chaotic circumstances.

The “Be Water” nature of Hong Kong’s protests means that crowds move quickly and spread across the city. They might stage a protest in the central business district one weekend, then industrial neighborhoods and far-flung suburban towns the next. And a lot is happening at any one time at each protest. One of the key difficulties for protesters is to figure out what’s happening in the crowded, fast-changing, and often chaotic circumstances.

Citizen-led efforts to map protests in real-time are an attempt to address those challenges and answer some pressing questions for protesters and bystanders alike: Where should they go? Where have tear gas and water cannons been deployed? Where are police advancing, and are there armed thugs attacking civilians?

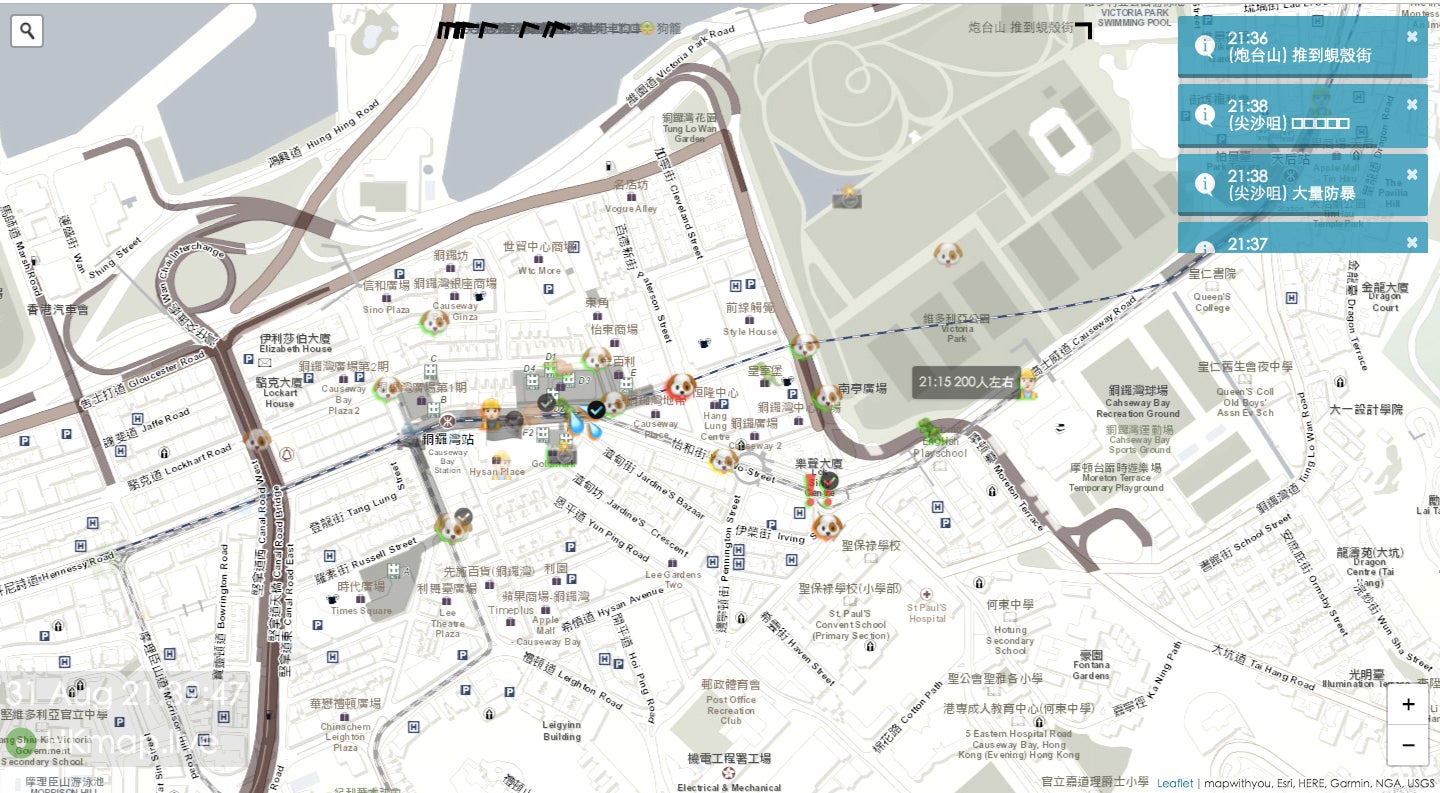

One of the most widely used real-time maps of the protests is HKMap.live, a volunteer-run and crowdsourced effort that officially launched in early August. It’s a dynamic map of Hong Kong that users can zoom in and out of, much like Google Maps. But in addition to detailed street and building names, this one features various emoji to communicate information at a glance: a dog for police, a worker in a yellow hardhat for protesters, a dinosaur for the police’s black-clad special tactical squad, a white speech-bubble for tear gas, two exclamation marks for danger.

Founded by a finance professional in his 20s and who only wished to be identified as Kuma, HKMap is an attempt to level the playing field between protesters and officers, he said in an interview over chat app Telegram. While earlier on in the protest movement people relied on text-based, on-the-ground live updates through public Telegram channels, Kuma found these to be too scattered to be effective, and hard to visualize unless someone knew the particular neighborhood inside out.

“The huge asymmetric information between protesters and officers led to multiple occasions of surround and capture,” said Kuma. Passersby and non-frontline protesters could also make use of the map, he said, to avoid tense conflict zones. After some of his friends were arrested in late July, he decided to build HKMap.

As a crowdsourced map, anyone can post time-stamped updates after logging in through a simple verification process via Telegram. A small team of moderators then fact check the post against live streams, news outlets, and administrators of other trusted Telegram groups. Once verified, the post gets a checkmark. Users who post false or unreliable information have their entries removed, and may be booted from the platform. To minimize security risks, Kuma is the sole administrator of the HKMap domain. They also use Project Galileo—a free cybersecurity service provided by internet security firm Cloudflare to at-risk public interest websites—to block malicious IP addresses and to protect the website against network attacks. According to Kuma, HKMap has had as many as 200,000 unique users in a single day, and more than 10,000 registered users who, in addition to contributing updates, can up- and down-vote posts on the map.

While speedy because of its crowdsourced nature, the fact that almost anyone can post on HKMap means a small amount of incorrect information inevitably slips past moderators. ”There are always speed-accuracy trade-offs,” said Kuma.

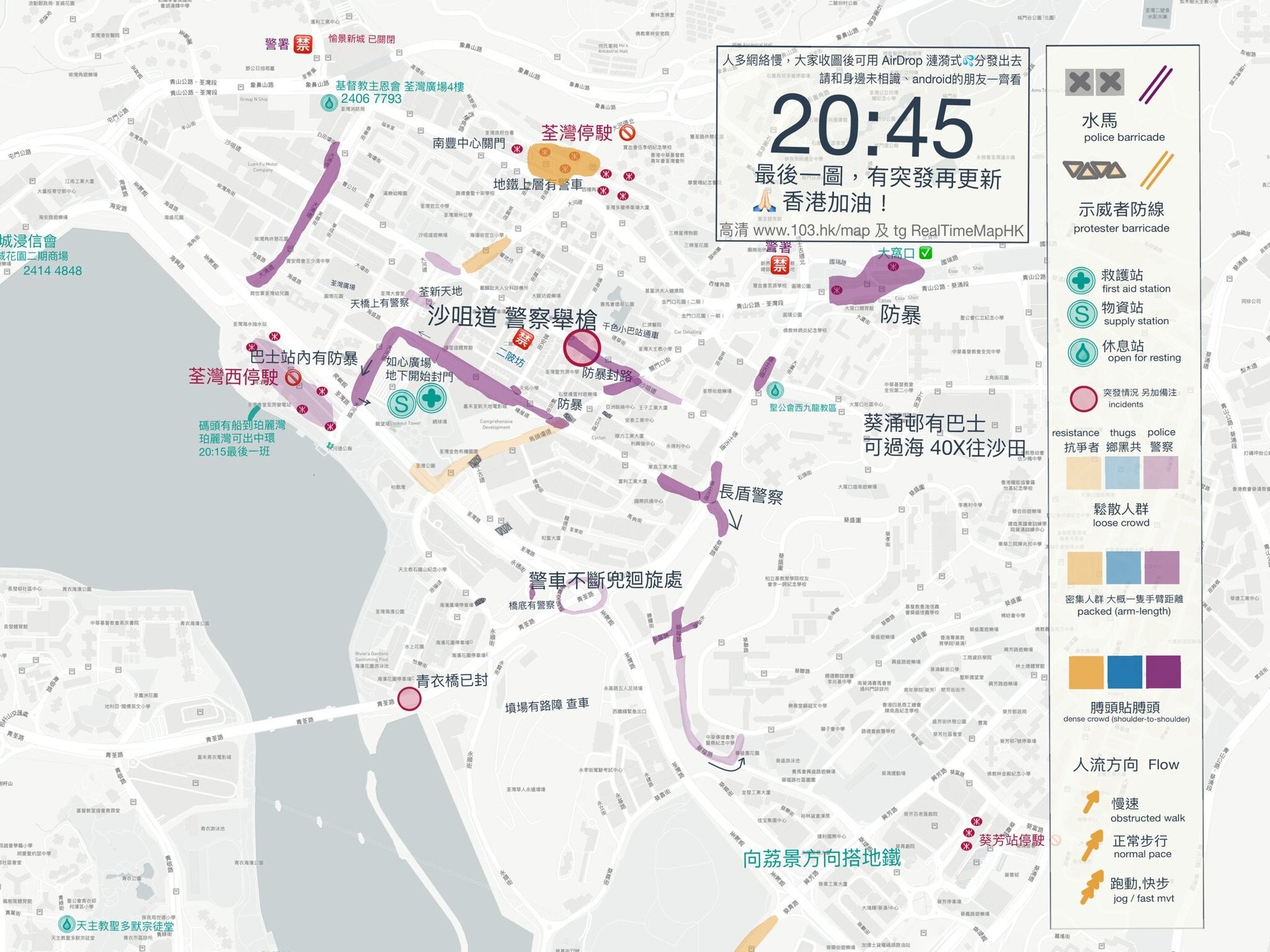

Luckily, another citizen-mapping initiative called 103.hk helps to make up for accuracy, even if it lacks the speed of HKMap. Unlike the dynamic and interactive nature of HKMap, 103.hk pushes out a single static map as a photo file. During protests, a new map is published on its website and distributed to various Telegram channels multiple times an hour. The map is color-coded to distinguish between protesters, thugs, and police, with darker shades reflecting the density of the crowd. It also uses arrows to show crowd speed, and icons to identify things like protester barricades and first-aid stations.

“I wanted something where you could look and go, ‘OK, this is the protesters, this is the protest, this is where there’s a black flag, where there’s tear gas, where you need to go,’ That was the idea,” explained 103.hk’s founder and administrator, an educator in his 40s who only wanted to be identified as Orca. “Black flag” refers to banners police raise to warn protesters of the imminent deployment of tear gas.

A small team of volunteers help to produce the maps. Out on the frontlines are “runners” dressed as regular passersby so as not to attract too much unwanted attention. Working with pen and paper on a clipboard, or through an illustrator app on an iPad, the runners mark up a blank map with the latest updates. The so-called “integrator” in the control room then assembles the updates, adding additional information from live-streams and news sources, to collate all available information at that moment into a single map, which is then published online and sent out via Telegram.

In crowded situations where internet access may be near-nonexistent, Orca encourages protesters on the edge of a crowd—where data coverage is better—to download the map, then AirDrop it into the crowd so it can make its way deep into the middle. “We call it rippling out, or rather rippling in,” he said. At its peak, the 103.hk website saw 600,000 hits during a march on Aug. 18 march. But because the map is sent out via so many channels, it’s hard to gauge exactly how many are using it.

With a bare-bones team putting in long hours during every protest, and with seemingly endless weeks of demonstrations ahead, Orca is well aware of the risk of burning out. “We’re all tired. But we try to do it as long as we can,” he said.

These maps have acquired greater importance in recent weeks, as police seem intent on closing down vast swathes of the city’s subway system, even ahead of authorized demonstrations, affecting not just protesters but tens of thousands of residents and visitors who depend on the metro.

“I see our role as a kind of a public service to people to know what the situation is so they can make their own decisions, especially when the police block off the majority of the escape routes and there’s no transport out of a place,” said Orca.