China’s Twitter operation focused on this exiled tycoon before Hong Kong protests

Twitter removed nearly 1,000 accounts last month, describing them as the “most active” of a network of 200,000 accounts suspended as part of a “significant state-backed information operation” by Beijing against Hong Kong protesters. Analysis of tweets from those accounts by the think-tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute has found that these accounts didn’t start their activities with the eruption of a political protest movement in Hong Kong against a hated extradition bill.

Twitter removed nearly 1,000 accounts last month, describing them as the “most active” of a network of 200,000 accounts suspended as part of a “significant state-backed information operation” by Beijing against Hong Kong protesters. Analysis of tweets from those accounts by the think-tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute has found that these accounts didn’t start their activities with the eruption of a political protest movement in Hong Kong against a hated extradition bill.

ASPI found that only about 112 of the 936 accounts publicly identified by Twitter substantially focused on Hong Kong, accounting for 1,600 tweets in total. But before tweets about Hong Kong saw an uptick in April of this year, they focused on other people the Communist Party of China deems opponents.

Here is a look at who they are.

Exiled Chinese tycoon Guo Wengui

China’s most high-profile exiled businessman, the property tycoon also known as Miles Kwok, has been based in the United States since 2017. He left China after a close associate was arrested for corruption. From New York, he frequently levels accusations of corruption against China’s ruling elite in televised interviews or on Twitter. Those he’s accused include the family of Wang Qishan, the former anti-corruption czar who is now vice president.

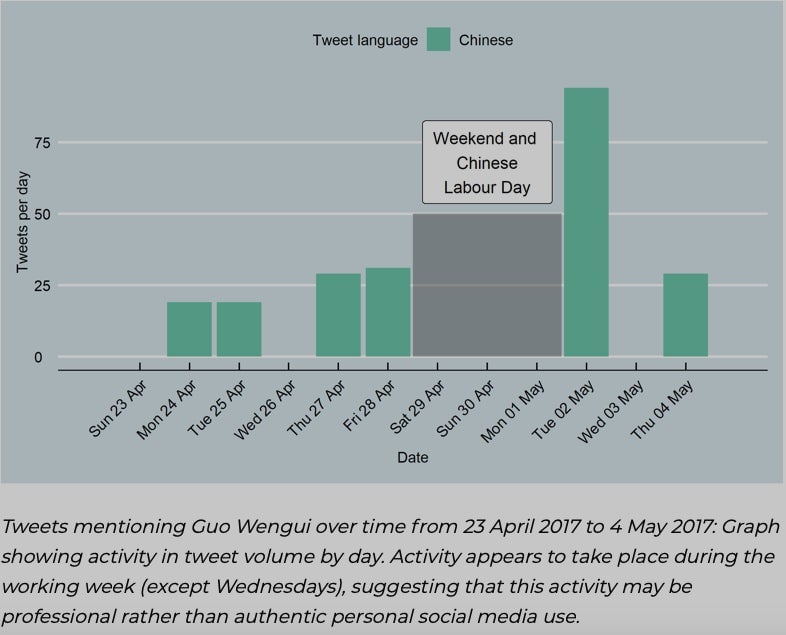

The campaign against Guo has been the most extensive by far, the ASPI report said. It appears to have begun on April 24, 2017 and continued till around July this year—around the time of a Wall Street Journal report (paywall) on a US firm’s allegation he had spied for China. In total, at least 38,732 tweets from 618 accounts directly targeted him, some of which appeared to be prescheduled, said the report. The tweets were largely criticisms of either Guo’s character or cast aspersions on his relationships with anti-China US politicians such as Steve Bannon.

Detained Hong Kong book seller Gui Minhai

Swedish citizen Gui was the co-owner of a Hong Kong publisher well-known for works about the dirty laundry of China’s Party elite. Gui went missing in October 2015 from Thailand, as he was reportedly preparing to publish a book about the love life of Chinese president Xi Jinping. He was one of five Hong Kong book sellers to go missing that year, only to turn up later in mainland China.

In January 2016, Gui appeared on Chinese state television and made a tearful confession, saying that he had killed a 20-year-old college student while driving drunk in southeastern China in December 2003. Rights groups believe this to be another example of a televised confession coerced by Chinese authorities. In October 2017, China said it released Gui, but according to media reports, he remains in detention in China after being snatched from a Beijing-bound train by plainclothes Chinese police in January 2018. Gui was last heard of in February that year, when he appeared in front of a bunch of reporters to make another confession, accusing Sweden of “sensationalizing” this episode and tricking him into plotting to flee China.

The tweets against Gui date to the day when he was snatched from the train, and ended about a month later, with ASPI describing them as “a short-term campaign intended to influence the opinions of overseas Chinese.” All of the 350 tweets are entirely in Chinese, and mostly accuse Gui of being a coward for wanting to leave China.

Detained human rights lawyer Yu Wensheng

Almost around the same time when the Twitter accounts started to attack Gui, another campaign also emerged, with its target being Yu, a human rights lawyer and outspoken critic of Beijing. Yu was arrested by Chinese authorities on January 19, 2018, when he was walking his child to school, according to AFP.

Yu is probably best known for his lawsuit filed against the Chinese government for the country’s chronic smog problem, together with other lawyers back in 2017. Yu has also defended people detained for their support of Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella Movement democracy protests, and fellow civil rights lawyers. Hours before his detention in 2018, he released an open letter advocating five reforms to China’s constitution, including the introduction of multi-party elections.

The Twitter campaign against Yu was, in comparison with the other attacked figures, smaller in scale and shorter in time. A total of 218 tweets from 80 accounts attacked the lawyer between Jan. 23 to Jan. 31 in 2018, said the report. Most of the accounts condemn Yu for his alleged violence against the police as shown in a doctored video in which he appears to resist the arrest and attempt to hit an officer.

Protesting veterans from China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA)

Given there are nearly 60 million veterans of its army, Beijing is increasingly wary of military veterans’ sporadic protests across China for better retirement benefits. The Twitter campaign against this group started on Dec. 9, 2018, shortly after Chinese state media said Chinese police arrested 10 veterans involved in an “illegal” demonstration that took place in Shandong province in October that year.

“A small but structured information operation” kicked off on Twitter on the day when the news was reported and continued till the evening of that day, according to the report. Most of the accounts condemned the “violent behavior” of the arrested veterans, and called for them to be punished.