Walmart dodged up to $2.6 billion in US tax through a “fictitious” Chinese entity, former executive says

Walmart, the world’s largest company, “improperly avoided” up to $2.6 billion in US taxes through an elaborate tax dodge involving a “fictitious” Chinese entity, according to documents authored by a former Walmart executive and reviewed by Quartz.

Walmart, the world’s largest company, “improperly avoided” up to $2.6 billion in US taxes through an elaborate tax dodge involving a “fictitious” Chinese entity, according to documents authored by a former Walmart executive and reviewed by Quartz.

Even in an era of rampant corporate tax avoidance, it’s rare to see inside details of such a case in which, experts say, the US Internal Revenue Service could have a legitimate claim to a large amount of taxes avoided by a major company. If the IRS aimed to reclaim all the avoided taxes, it would be seeking a figure close to the largest tax repayment in US history—behind GlaxoSmithKline’s $3.4 billion settlement with the IRS in 2006.

Chinese tax authorities may also have questions about the arrangement, a Chinese tax law expert said.

Walmart’s arrangement, internally named “Project Flex,” revolved around the company’s payments to its Chinese subsidiary in Shenzhen, from which it sources many of the billions of dollars of Chinese goods it imports every year, the former executive wrote in a presentation explaining it. To avoid paying tax in either the US or China, Walmart created a “tax nowhere” entity that neither country would claim jurisdiction over, according to the former executive.

“The goal of Project Flex was to create something from nothing, that China would say is nothing, but which the US tax rules would be required to embrace,” the former executive wrote in the presentation. Tax law experts confirmed the executive’s thesis that the structure does not exist in Chinese law and said the IRS would have grounds to challenge Walmart.

Walmart rejected that assessment. “These issues were raised years ago, independently and thoroughly investigated at the time and the tax year covering the matter has been closed by the IRS,” a company spokesman said in an emailed statement. “The IRS also has an on-site office at Walmart full-time, year-round. Through our participation in the IRS Compliance Assurance Process [CAP] program, we have open and transparent discussions, proactively share information about corporate structures as they occur, including this matter, and provide other materials the IRS requests.” Walmart has been in the voluntary CAP program since 2005.

The Walmart spokesman declined to comment on when the independent investigation took place and which law firm conducted it, whether the IRS was aware of the structure’s legal viability in China, and which tax year the IRS has closed. Project Flex started in 2014, and would become unnecessary by 2017 under US tax law changes. Walmart avoided around $2 billion in tax through a “deemed dividend,” obtained in 2014, and then dodged around $200 million per year thereafter, the former executive argued. If the IRS closed the 2014 tax year for Walmart, it’s possible it wouldn’t be able to go after the $2 billion. (EY, the accounting firm that helped Walmart devise the arrangement according to the former executive’s documents, declined to comment for this story.)

The documents were shown to Quartz by a third party who had been sent the documents by the former Walmart executive. The former executive, who declined to comment on this story, citing a confidentiality agreement with Walmart, wrote the documents with a view to sending them to the IRS, which gives financial rewards to whistleblowers. It’s unclear, however, if they were ever actually sent to the agency.

The former executive’s files include the legal contract for the “tax nowhere” entity—an ostensibly Chinese “joint venture”—and a lengthy slide deck and detailed legal memo explaining why the IRS has a claim to the money, both written by the former executive. A person familiar with the arrangement confirmed that the structure was set up as described in the documents. Much of the structure can also be seen in internal Walmart files obtained in the Paradise Papers leak, which the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists shared with Quartz.

Some of the machinations are “egregious,” said Wei Cui, an expert in American and Chinese tax law and professor at the University of British Columbia, who reviewed the files for Quartz. “The idea is that they create an entity that did nothing, completely a piece of paper,” he said. “[The] arrangement is aggressive—there’s no question about that.”

If the IRS took Walmart to court, it would have a good shot at recovering at least some of the $2.6 billion, tax experts said. “I think there is a good argument based on the facts presented by the whistleblower that the structure actually does not work [as a means of avoiding US tax],” said Omri Marian, a tax-law professor at the University of California, Irvine. He added that he couldn’t be sure of the strength of any legal challenge, since the files don’t include the legal opinion commissioned by Walmart, which, the former executive’s memo says, argued the structure would hold up in court.

While the structure might not stand up as a tax-avoidance mechanism, there’s no allegation that Walmart broke US law, since tax avoidance on its own is not illegal. An IRS spokesperson declined to comment for this story, citing a federal law that prohibits the agency from discussing specific taxpayers.

Walmart, with annual revenue hitting $501 billion in 2018, has topped the Fortune Global 500 every year since 2014. Its owners, the Waltons, reportedly the world’s richest family, are said to add $100 million per day to their $191 billion fortune. A 2015 report by the Americans for Tax Fairness campaign group alleged that Walmart had placed assets worth at least $76 billion in tax havens where it had no retail stores—a figure equal to 37% of the company’s total assets at the time. (Walmart called the group’s findings “incomplete and erroneous.”)

“Our old report showed there was an octopus. Its foreign subsidiaries—and the secretive nature of these foreign subsidiaries—was remarkable and it appeared to be a substantial tax dodge,” said Frank Clemente, Americans for Tax Fairness’s executive director and co-author of the 2015 report. Project Flex “seems to me to be some smoking-gun evidence of the extent to which Walmart engaged in subterfuge and tax dodging.”

Walmart is far from alone in using offshore mechanisms to avoid tax. In total, US multinationals held around $1 trillion offshore by the end of 2017, the Federal Reserve estimated, with giants such as Apple and Microsoft brazenly, and legally, booking profits in tax havens like Ireland.

How Project Flex worked

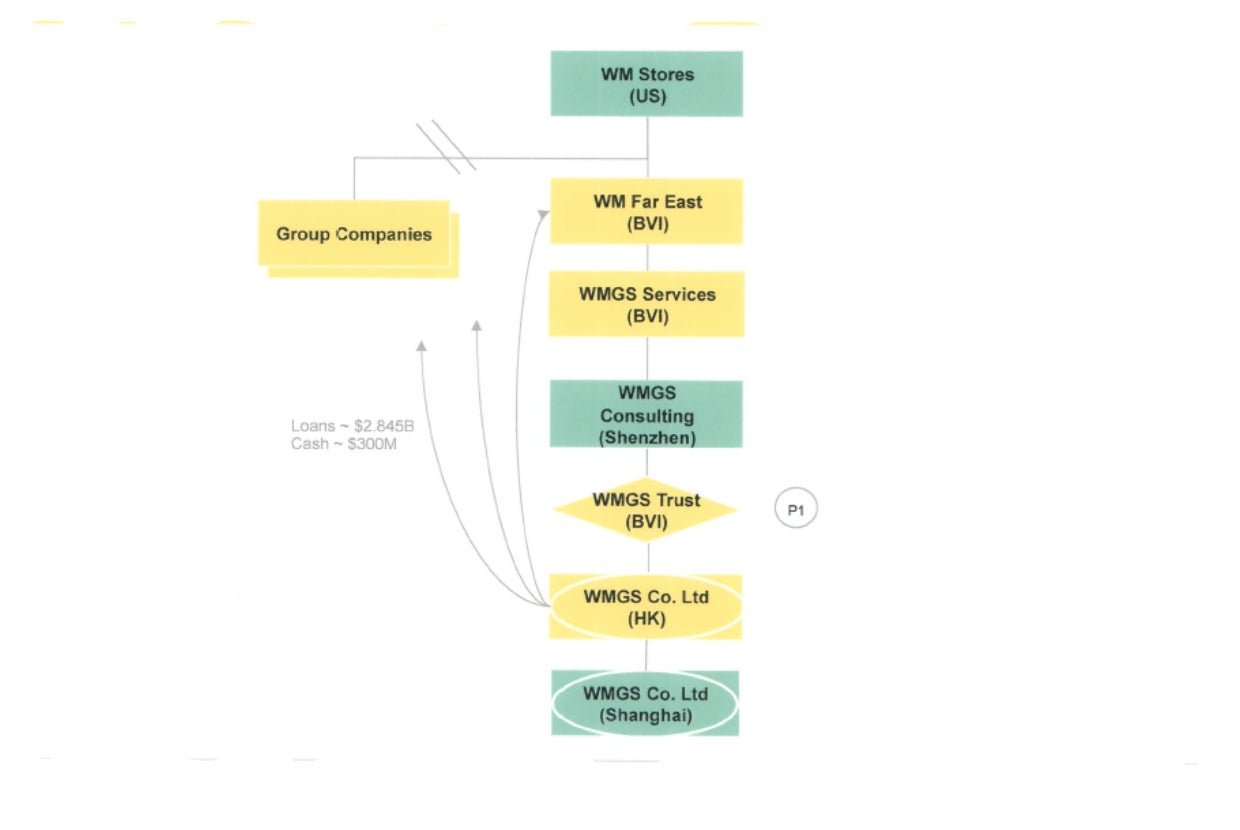

Walmart paid its Shenzhen subsidiary via a commission on the imported goods, sending the commission from the US parent company to a subsidiary in Hong Kong, which then sent it on to another subsidiary in Shenzhen to pay for Walmart’s 1,000-employee operation there, according to the documents.

A second former Walmart employee, with direct knowledge of its taxes, confirmed that Walmart held the Hong Kong subsidiary via this structure, which can also be seen in an internal company slide from 2009, found in the Paradise Papers.

Walmart paid a 1.4% commission on the pre-shipping cost of the goods to the Shenzhen entity, but declared to US authorities that it was paying an amount worth 5% to a foreign subsidiary, according to the former executive’s account. It didn’t have to pay US tax on that money, since it was just presumed to be going to another part of the same company. Walmart then kept the remaining 3.6% in the Hong Kong subsidiary, the former executive’s files say. This amounted to stashing around $600 million per year in the Hong Kong subsidiary, which had “no employees or activities,” the former executive wrote.

The former Walmart tax employee summarized the goal for Quartz: “They wanted to park some profits in places where it wasn’t subject to tax—neither in China, nor in the US.”

At the time, that was likely an acceptable tax-avoidance arrangement under US law, according to the documents. The Hong Kong arrangement had been in place since 2001, according to the former executive’s memo. Filings with Hong Kong’s corporate registry show the entity, WMGS Co. Ltd, was created that year.

While sitting in Hong Kong, the money could amass millions of dollars in interest without being taxed. Many US multinationals allow money to accrue interest offshore and wait until a new presidential administration grants a tax holiday, allowing the companies to repatriate it at discounted rates. At least some of the money was used to make loans to finance other Walmart entities, the person familiar with the arrangement said.

To avoid paying tax in Hong Kong, Walmart wasn’t allowed to do substantive business there, creating headaches even if it wanted to just hold meetings, the former Walmart tax employee said. “People didn’t want to go to the mainland—they wanted to go to Hong Kong, it’s easier to fly into,” the person said. “Under the old structure, that would be discouraged because you’d be breaching a deal [with the Hong Kong authorities].”

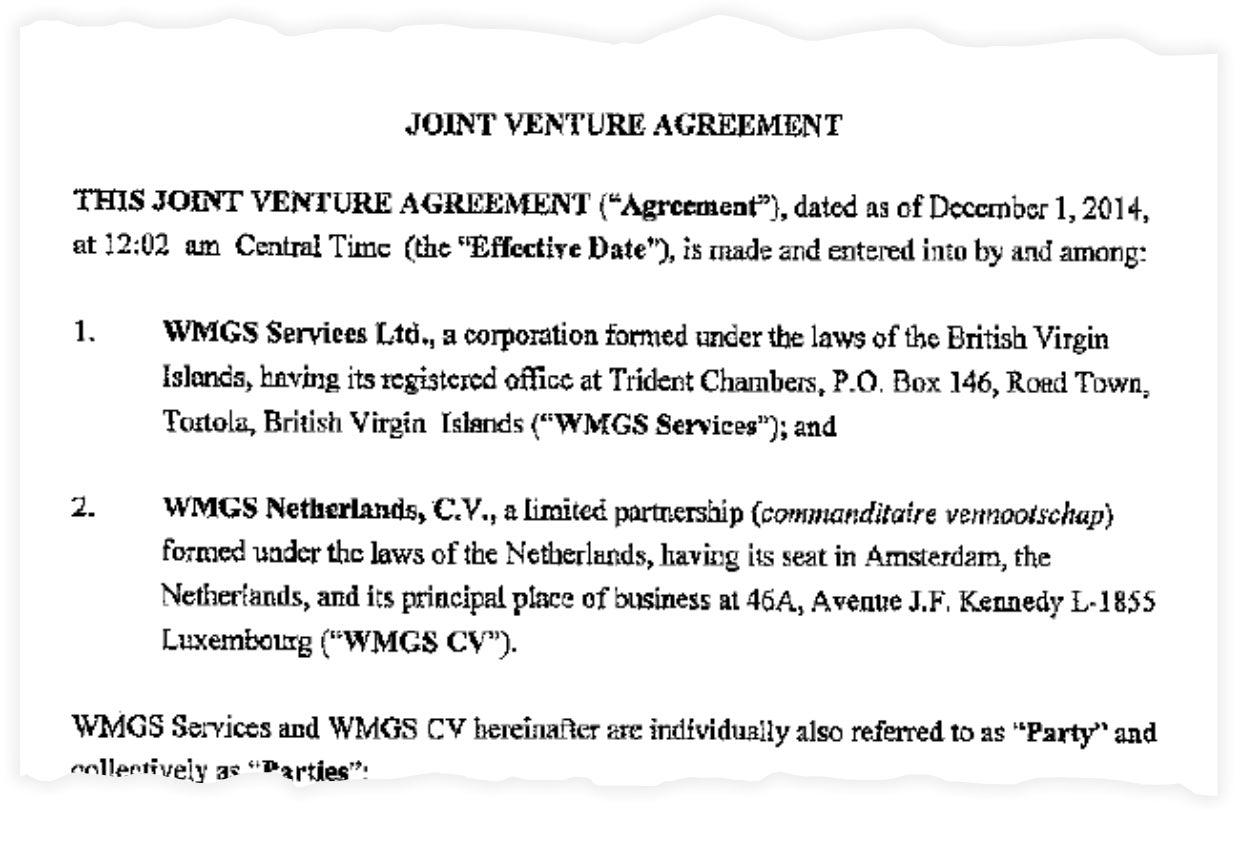

In November 2014, however, Walmart changed the structure of the arrangement. It went through a highly complex 11-step process to create a “joint venture” between Walmart’s British Virgin Islands and Dutch subsidiaries, the former executive wrote. Under Project Flex, the “joint venture” replaced the Hong Kong subsidiary. The former executive’s documents include a copy of the “joint venture” agreement signed by Walmart’s then-global head of tax and a vice president in its Global Treasury department, who is also listed as a director of the Hong Kong subsidiary on the company’s public filings.

This joint venture claimed to be Chinese. Its legal agreement includes just one line saying it “shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of China.” Since the “joint venture” was ostensibly based in China, Walmart was then able to claim a US tax credit on that annual $600 million in revenue because US authorities would assume it was still being taxed on that money in China, the former executive wrote. It also didn’t pay tax in China on the “joint venture,” according to the former executive’s files.

However, the type of joint venture created under Project Flex doesn’t exist as a valid entity in Chinese law, according to two Chinese tax law experts and the former executive. “This is a fictitious joint venture,” said Jinyan Li, a professor at York University in Toronto and expert on Chinese tax law. “It makes me feel so mad when I see people taking these things seriously for tax purposes. This is really not a corporation, not any entity recognized by Chinese law.” Walmart said it had the structure investigated by an independent law firm.

Further, the former executive noted in the presentation, by marrying the BVI entity with the Dutch entity, Walmart was creating a “joint venture” with itself. The BVI entity and its parent company, Wal-Mart Far East Holdings, already owned the Dutch entity, the former executive said. Dutch public filings confirm that structure, and show the firm was created the day before the “joint venture” agreement was signed. “What’s a good reason for someone to do something not by itself but with another entity created by itself? It’s very hard to say that there’s any purpose for that [aside from tax avoidance],” said Cui. “Given what I’ve seen, I can’t think of any other reasons.”

The person familiar with the arrangement said the “joint venture” was created for “business reasons.” “The old structure was very restrictive on what activities they could perform in Hong Kong,” the person said, adding that the company wanted to hire more talent in Hong Kong and attend trade shows and engage in other business activity there. “It didn’t necessarily require a joint venture, but the JV was the most efficient way to enable that without a bunch of ripple effects.” The person said Walmart considered the argument described by Cui and Li, and consulted with Chinese legal counsel when setting up the structure.

Potential IRS issues

The US tax exemption that would have allowed Walmart to dodge payments on the money stashed in the JV exists because US authorities expect that when a company transfers money between two of its entities in a foreign country, that cash will have been taxed in that country. However, since the “joint venture” didn’t really exist under Chinese law and Chinese authorities were likely not even aware of it, the former executive contended that Walmart owes around $200 million per year in US tax on the $600 million annually sent to the allegedly fictitious entity.

The person familiar with Project Flex said that Walmart “went through some pretty significant negotiations and discussions with the IRS” to support the 5% commission figure, and that it disclosed the full structure to the agency.

If Project Flex continued until 2017, when changes to US tax law would have dented some of its avoidance strategies, the IRS would have grounds to sue Walmart for around $600 million based on the “joint venture,” based on the calculations in the former executive’s presentation. The independent US tax experts told Quartz they agreed. There could be a separate argument to sue for an extra $2 billion, the former executive argued.

Allowing Walmart to use the “joint venture” structure would make one element of the US tax code “meaningless,” the former executive argued in the presentation. “Companies will be able to create ‘same country’ income anywhere in the world without the corresponding burden of having to form a local country entity that would be subject to local country taxes.”

Based on the former executive’s presentation, the IRS would have a good case, Marian argued, adding that tax courts can impose extra penalties for what is deemed to be aggressive avoidance, as well as demand repayment of $600 million plus interest. Extra penalties can be as high as 40% of the initial amount of tax avoided.

Cui, who agreed the IRS would have a decent case, noted the agency would also take on a “litigation risk” by bringing it to court. “There’s not a lot of law in this area—it would be hard to predict how a judge would rule on this very technical issue,” he said, adding he is “sympathetic” to the argument that a decision in favor of Walmart would make it easy for other firms to abuse the tax exemption Walmart used.

Cui said the Chinese government also could—and “should”—have taxed Walmart on the money. However, Beijing likely tolerates the avoidance because it doesn’t want to lose business from big multinationals, he said. “If China decides to crack down on Walmart, which is probably the last thing it wants to do now, it would have to do that to a lot of others,” he said. “Walmart’s Shenzhen operation is a big deal, so people are happy enough.”

Li disagrees, arguing that upon learning about the scheme, Chinese tax authorities “would be interested—they will probably give Walmart’s representative in China a call.” The crux of the matter is whether Walmart has previously told China 1.4% is the market rate for a commission for such services—and whether it has the data to persuade authorities that is the case, she says.

“It’s like a magic show, and the intended audience is the IRS,” she said. “The Chinese may look at it and say, ‘Hey, this looks interesting. Is our interest hurt?’ They may look and say, ‘We’re still happy with 1.4%.’ They may not do anything; they may be offended that China is used as a prompt for this show put on for the IRS, but look at their interests and say, ‘We remain happy with 1.4%.’”

Beyond $200 million in tax avoided per year, the company essentially paid itself a dividend of around $6 billion by shifting the scheme from the Hong Kong shell company to the “joint venture,” the former executive argues in the presentation, saying EY and Walmart had valued the arrangement at around that sum. That “deemed dividend” should incur $2 billion more in taxes, the executive argued. Marian said he agrees that the transaction, as described by the former executive, could be judged a “deemed dividend” but can’t be certain it would succeed in court without analyzing the counter-argument written by Walmart’s lawyers. Cui said it wouldn’t be a “slam dunk” in court. If the IRS signed off on the 2014 tax year, Walmart is probably safe from any legal challenge over the $2 billion, since the “deemed dividend” occurred when the structure changed in 2014.

The independent auditor and tax consultant

EY has been Walmart’s auditor since 1969, earning $24.5 million for its services in fiscal year 2018 alone. In 2014, while EY’s auditors independently analyzed Walmart’s accounts, its tax consultants advised it on how to structure Project Flex, the former executive alleged, writing that they were paid “hundreds of thousands of dollars” for the plan. Major accounting firms are facing a series of crises around the world, many of which are related to perceived conflicts of interest.

In 2014, a US Senate investigation into manufacturing firm Caterpillar’s taxes said that EY’s rival PwC raised “significant conflict of interest concerns” by acting as both an auditor and tax consultant to the firm—just as EY did for Walmart. It recommended that the government’s audit regulator, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, ban accountancy firms from fulfilling both roles for one company. The board reportedly opened an investigation into whether the case represented a conflict for PwC. In the UK, where accountancy firms are trying to avoid auditing scandal-plagued retailer Sports Direct, both EY and Deloitte have insisted they are conflicted out, since they have done non-audit work for the company or an entity it has bought.

EY’s tenure as Walmart’s auditor last came under scrutiny in 2015, when a Walmart shareholder accused EY of knowing Walmart may have paid bribes in Mexico a long time before the accountancy disclosed the matter to authorities. Walmart agreed to pay a $282 million settlement over the case earlier this year. At the time, EY declined to comment on matters involving its clients.