MIT has a plan to measure the impact of 2016 election interference

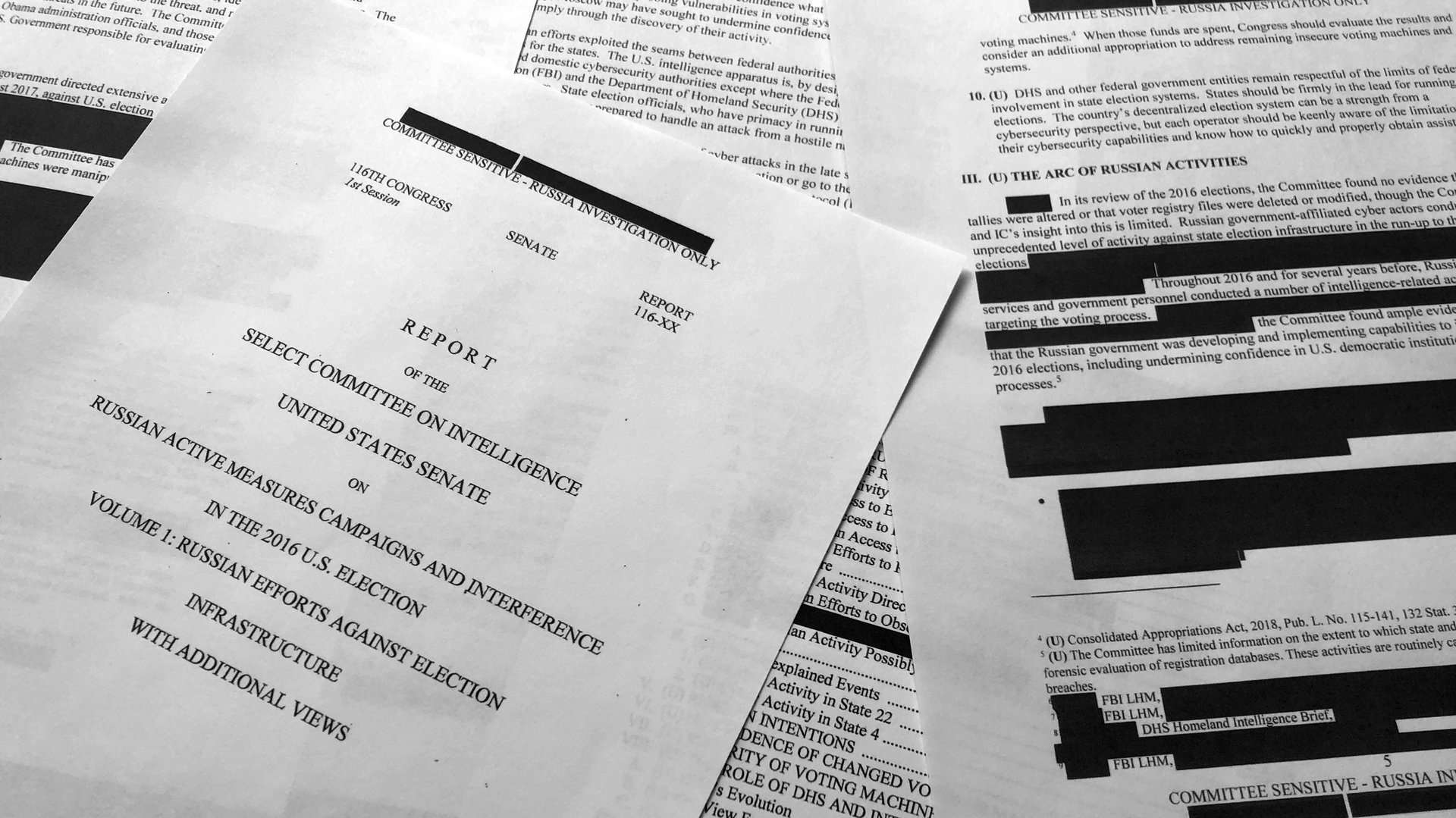

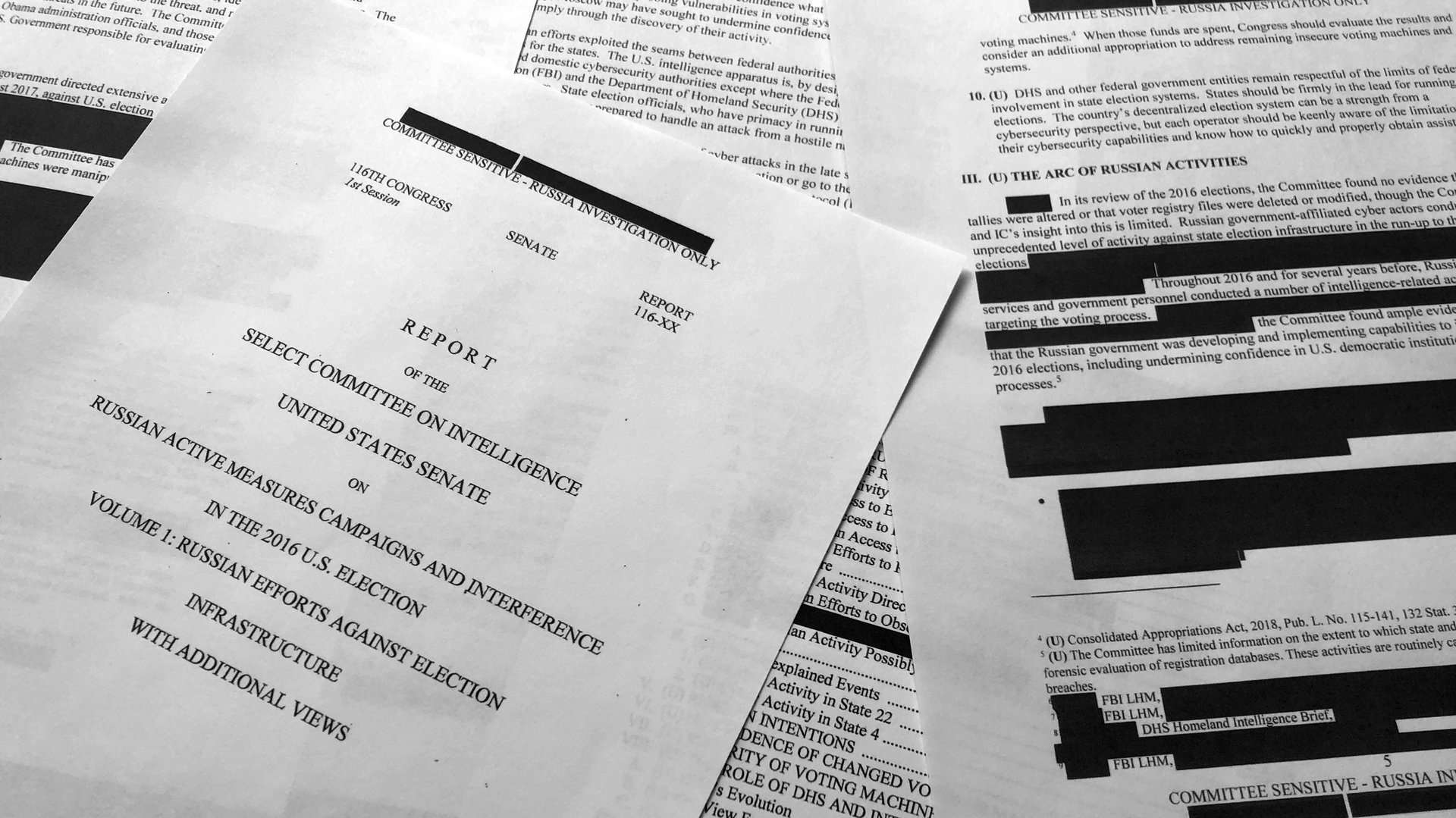

The Mueller report made it clear, and two Senate Intelligence Committee reports confirmed it: There is no question that there was Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

The Mueller report made it clear, and two Senate Intelligence Committee reports confirmed it: There is no question that there was Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

More than a quarter of voting-age Americans were exposed to Russian-sponsored misinformation in the weeks prior to the vote, and hundreds of millions of fake-news posts were published on social media specifically with the intent of affecting the result of the election.

So, we know it happened—and can reasonably predict it will happen again in the 2020 election. What we have yet to understand is how much of an the impact it had. Did Americans change their voting behavior because of fake news they read online? And if so, to what extent?

A new report published last week in Science by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) says those questions can be answered. Looking at the body of knowledge in how social media affects behavior in general, the MIT authors have outlined out a four-point strategy to understand the impact of fake news and social-media manipulation.

Co-author Sinan Aral, an MIT professor of management, says the impact can be quantified, thanks to a vast body of research on social-media messaging and its influence on user behavior. The plan proposed in the paper describes four steps toward that end:

- Quantify and catalog impressions of deliberately manipulative content; the researchers would need to know what content was promoted organically on social media, or through paid ads, and which was shared by the users, when, and what kind of content was more effective.

- Compare the findings with voting behavior; unlike voter turnout, voter choices aren’t public, so the data on exposure would need to aggregated and compiled in a way that can be compared with available aggregated data at the district level. This is a step in which data available on social media platforms (for instance, the information about the locations of users) would be fundamental.

- Quantify the actual impact of misinformation. This can be done by analyzing the reactions of people to varying quantities of misinformation, for instance by adapting the tests that social media platforms run on their own users to observe their reactions to different mix of content on their timelines.

- Compare the aggregated changes in voter behavior with actual election results, to understand whether and how the manipulation has impacted the final results.

Similar analysis can assess the effectiveness of debunking misinformation, which would help develop solutions to counter manipulation attempts. All of this, the authors warn, needs to be done quickly enough to keep pace with technological developments. “There’s dramatic potential danger in new forms of falsity,” Aral told Quartz, noting the an enormous threat posed by video, as the medium can feed the belief that seeing is believing.

Luckily, the kind of research proposed by the paper can have a fast turnaround. “This kind of analysis can be done not exactly in real time, but very quickly,” says Aral.

A big issue with all of this research: Privacy. User-behavior analysis is dependent on access to personal data, which in turn is susceptible to breaches or being misused, as Cambridge Analytica did. So far, digital platforms haven’t granted researchers access to the data necessary to perform their analysis, though it is possible to regulate it in a way that the data was ultimately supposed to be protected—by being aggregated and anonymized.

“It is possible for platform to become more transparent and more secure at the same time,” says Aral, noting that granting data access for analysis while otherwise maintaining strong protection of it would be vital