Geodesign is going to change the design world as we know it

We live in a time unparalleled in history, surrounded by an ongoing series of extraordinary scientific discoveries and technical innovations being made at an exponential rate. Each week seemingly brings us a new miracle, whether it’s AI and deep learning, nanotechnology, wireless mobility, self-driving cars, going to Mars, bioengineering, or CRISPR. The list of technical advancements is seemingly endless, many poised to change our lives forever.

We live in a time unparalleled in history, surrounded by an ongoing series of extraordinary scientific discoveries and technical innovations being made at an exponential rate. Each week seemingly brings us a new miracle, whether it’s AI and deep learning, nanotechnology, wireless mobility, self-driving cars, going to Mars, bioengineering, or CRISPR. The list of technical advancements is seemingly endless, many poised to change our lives forever.

Yet with all of these remarkable achievements, we have not been good custodians of our planet. Despite our scientific discovery and inventions—much of which is poised to empower and benefit the peoples of our world—there is little good news about the impact we humans are having upon life on Earth.

It’s getting worse with time. In the past 25 to 30 years, we’ve lost more than 10% of the global wilderness areas, and half of our coral reefs have died. We’re dumping about 8 million metric tons of plastics (and a vast array of other pollutants) into our oceans each year, and during this hour, we’ve lost another species to extinction.

Even where we’ve made significant progress, such as in reversing the damage to the Earth’s protective ozone layer by the banning CFC production, it is expected that a full recovery will take another 100 years—but only if we maintain our vigilance. Once the damage is done, revising it is enormously challenging, incredibly expensive, and sometimes impossible; we will not be getting back the species we have lost, for example, many of which will be gone before even having been discovered.

The vast majority of the qualified scientific community is well aware of the impacts of climate change, the unprecedented acceleration of species extinction, and the consequences of polluting our air and water. So why do we keep doing it?

Sometimes it’s denial or apathy, as it’s easy to dismiss things we can’t see, or the events we think won’t hit home in our lifetime. Many believe that someone else will fix it.

But the bigger problem is that we struggle to effectively communicate the reality and consequences of inaction to our citizens and their leaders. Rather than activating people, the media coverage now seems to be numbing people—they just don’t want to hear bad news anymore. They see these problems as being of such magnitude that they have no personal ability to affect the outcome. And so, they disengage. Or, worse still, they reject science, evidence, and knowledge in favor of misplaced optimism in the hyperbolic egos of those with self interest in preserving the status quo.

This is also leading to an unfortunate cynicism. “Do I really mind if we lose some random miniature purple frog from the rainforests in Brazil?” they wonder. The saddest reality of today is that many people, including some of our leaders, just don’t care. And if they do care, they believe that they are not personally in a position to positively impact the situation.

The bottom line is that we have to tell this story better. We have to get people to understand that there are things they can do both personally and collectively that both can and will make a difference.

But first, we need to give our citizens, government, industries, and developers the ability to accurately see into the future. Only then can we understand the cause and effect of our actions, and develop an informed consensus for how to move forward.

How far away is the future?

We need to focus on a near-term plan for our precious planet. Most people would consider “near term” to be the next two to five years, but when I say “near term,” I mean the next 250 years. That’s only a blip in the history of life on Earth, but on a human-scale timeline, it feels incomprehensible.

Because of our Darwinian survival instincts, we are wired to acknowledge and deal with our perceived immediate threats first. The rest can wait, and the farther away those threats seem, whether in time or proximity, the less attention they receive. This may be a reasonable strategy for the survival of an individual and their family, but it can result in decisions that will be catastrophic to future generations.

Instead of focusing on making the world better in our lifetime, these grand challenges must be thought of as focused and sustained efforts, handed from one generation to the next, and thoughtfully amended along the way.

Some societies are better at long-term thinking than others. Unsurprisingly, the ones that have been around the longest seem better at it than the newcomers. Japan, for example, has 3,146 companies that are over 200 years old, and more than 21,000 companies that are over 100 years old. I’ve heard of Japanese companies that have 250-year plans: For example, Konosuke Matsushita founded Panasonic in 1918 when he was 23 years old, and within 10 years announced a 250-year plan for his company. Most recently Masayoshi Son, the CEO of SoftBank Group, started a $100 billion Vision Fund that he expects to “grow 300 years down the road.”

In contrast, most American companies I’m familiar with have a five-year plan—and that’s what they consider long term. Of that, they’re comparatively serious about the first 18 months to two years, then the rest is just a spreadsheet that them make look good, so their investors won’t throw them out.

Building in accountability

With few exceptions, in today’s short-attention-span world where critical policy can be revealed in 140-character tweets, and vast companies are run based upon next-quarter results, long-term planning is one to three years—at most.

Why is this? Sustaining long-term visions and goals is very difficult with rapidly changing leadership. Under each new leadership, the solutions of the past rapidly become the problems of the future.

This statement holds true whether it’s in a corporation, the military, or politics. One of the things I’ve learned after decades of working all three sectors is that a common attribute of most new leaders is that they’re not particularly interested in executing the vision of their predecessors. They can’t fathom the concept of carrying forth an idea that their incumbent pioneered, and feel driven to make their own mark. It’s rare to find a leader who will carry on a torch that someone else has lit.

When we’re looking at endeavors that need to be continued for 250 years or longer to be effective—like the challenges climate change, sustainable and renewable energy, carbon neutrality, mitigation of air and water pollution, cleaning and regenerating our oceans, and nuclear waste management—or imperatives such as human rights, global education, health care, safety, and societal stability, what hope do we have if the goal posts change every four to 10 years?

A related challenge is that our leaders aren’t being held accountable for their actions—and their inactions. Many world leaders today will never pay the price for the terrible decisions they make now, as the ramifications won’t take effect for decades after they’ve left power. What process is there to make sure that leaders are culpable for their actions? How do we make smart daily decisions on things that will have impact hundreds of years from now? This is especially the case for unpopular decisions. The kinds of choices that require public sacrifice and the expenditure of money often aren’t made, because short-term thinking prioritizes putting human and capital resources toward issues that appear more urgent in the moment.

So what if we just stopped making decisions all together? Some people suggest it’s best to assume a luddite’s point of view on our future: to just stop exploration, stop research, stop advancing these frontiers, and stop innovation. (All of which are the key creative byproducts of human imagination.) But that doesn’t work, and it’s never worked in the past. If we worked hard enough to suppress progress, we could theoretically create another Dark Ages—but it’s contrary to the human spirit. We can’t stop humanity’s creativity. We can only give it bumper bars.

Society can and should add clear rules for the development of certain new technologies and require ethical practices to help manage potential consequences. It is perfectly fair to demand responsibility from the practitioners, but the reality is that slowing things down or expecting people to stop dreaming, thinking, and creating is neither an effective nor sustainable strategy. In fact, it is counterproductive, as effectively addressing many of our biggest environmental challenges will require new technologies and innovative solutions for success.

A new kind of leadership is required, backed by the peoples of our world, willing to sign up for the sacrifices needed to effect change, and committed to keep fighting the good fight. This is a simple necessity for future generations to flourish, and there are ample people ready to devote their lives to achieving these goals.

But if they are to succeed, we need to give them a new set of tools to deal with this class of long-term challenge: tools that let them look into the future and understand the consequences of both our actions and our inactions.

The good news is that I believe that there’s an emerging discipline that could do the trick. It’s a comparatively new practice that combines mapping, geographic information systems (GIS), building information modeling (BIM), economics, architecture, animation, physics, atmospheric science, big data, and storytelling. Yet most people haven’t even heard the word—I hadn’t myself until a few years ago when I was invited to keynote the field’s first summit in 2010.

It’s called geodesign.

What is geodesign?

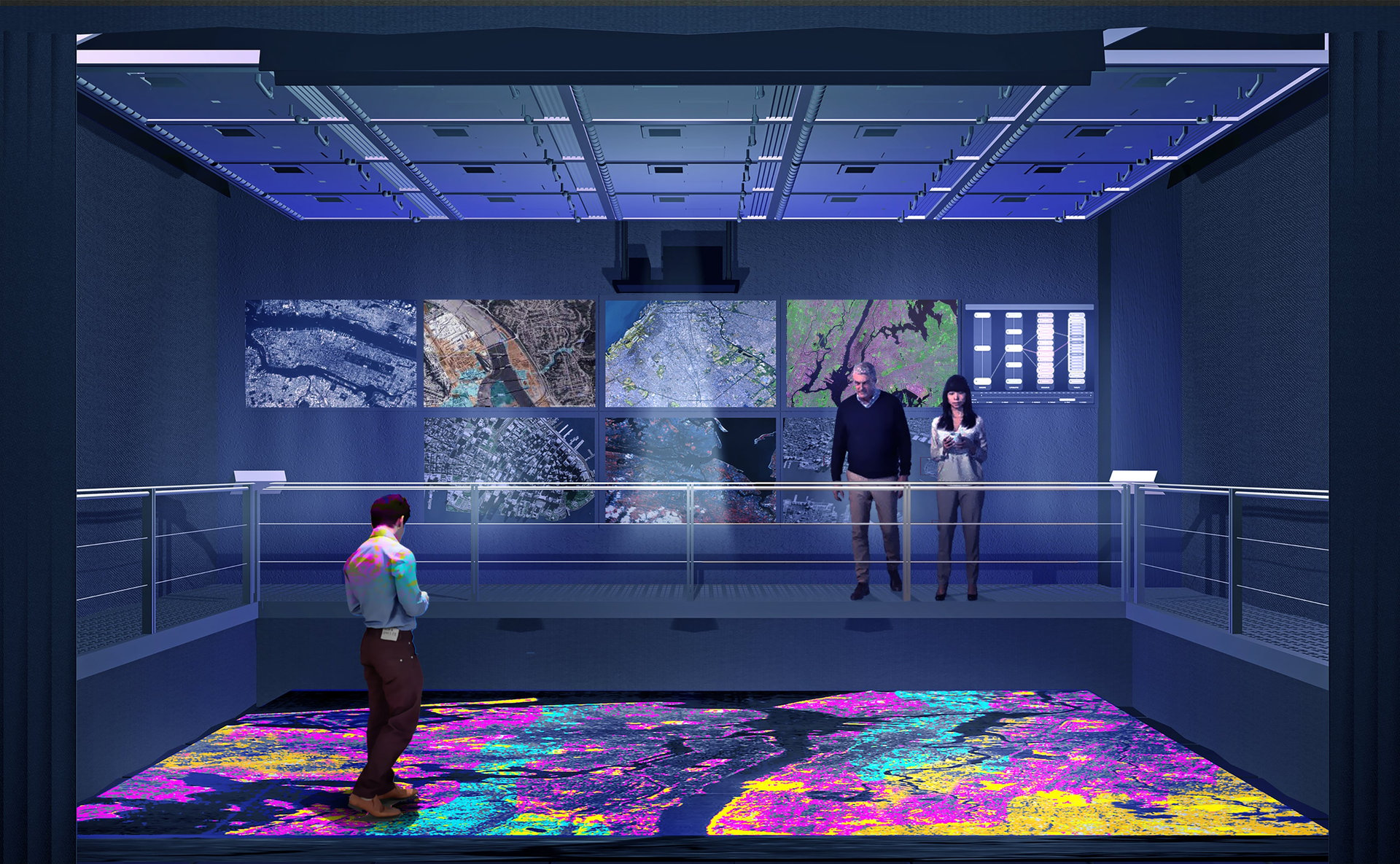

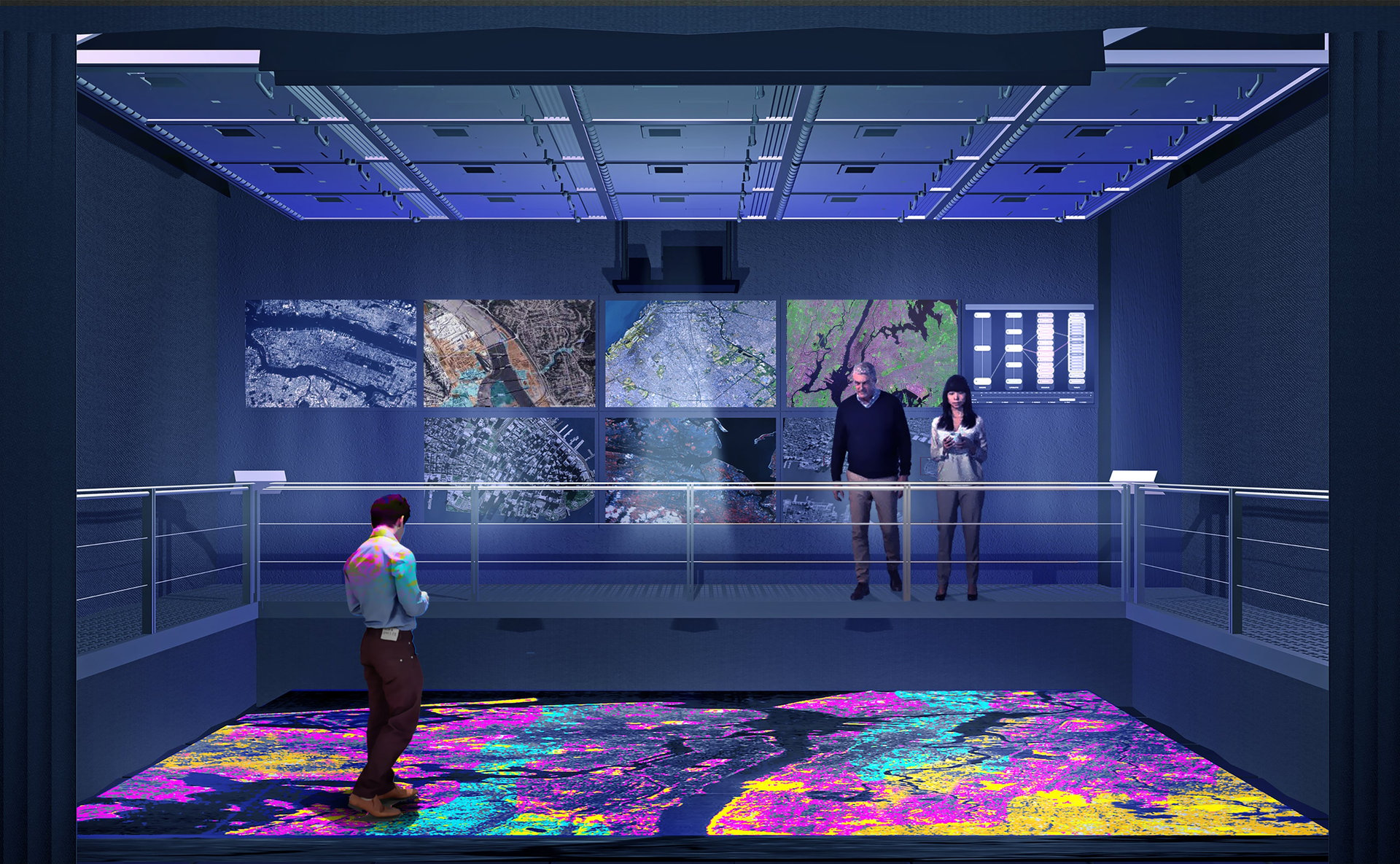

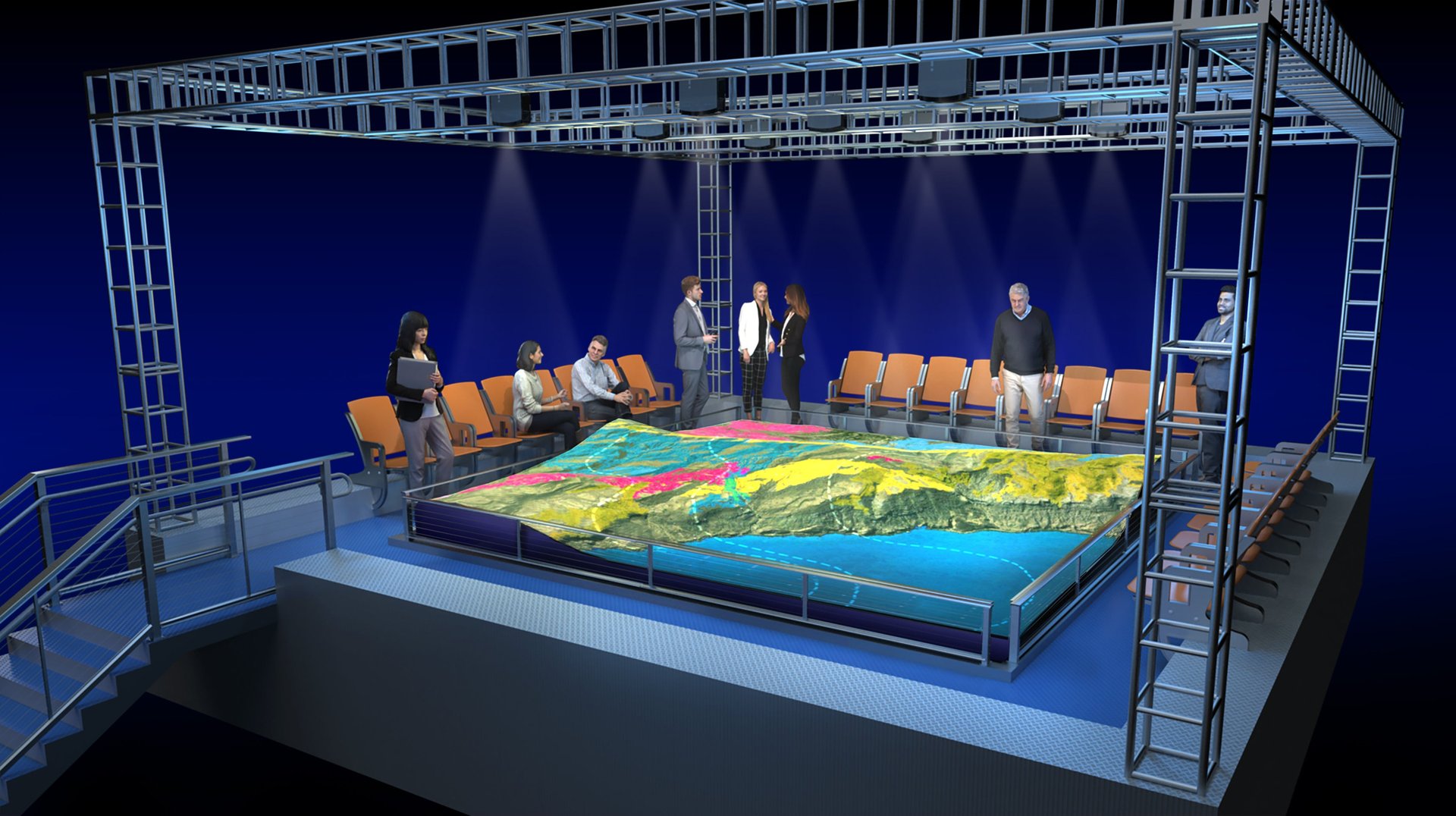

The idea of geodesign is pretty simple: It’s a way to visualize the future of our physical world, and to better understand the impact of our planned (and unplanned) future actions. It allows us to take massive sets of data about the workings of our natural and human-made systems; experiment with and optimize various design solutions, such as what we build, where we live, how we move, what we consume, and what we expend; and see how things will change over time, for better or worse.

The purpose is to give stakeholders from different disciplines the ability to communicate and work together to design better and more harmonious solutions for the constructed and natural world. When it works as intended, this can allow us to visualize our path in order to make wiser and more timely design and policy decisions, today.

It brings people together from a wide variety of disciplines—designers, creators, inventors, scientists, planners, politicians, architects, engineers—and enables them to design solutions to challenges in both the human-made and natural world. Through modeling, simulation, and visualization, they collaboratively create and see the future effects of their work, and thus make superior decisions.

We can design roads, housing, factories, farms, and schools. We can choose what to develop, where, and try different forms of energy such as solar, wind, or nuclear to power it. After setting these parameters, we let computer models predict tomorrow by showing us what things will look like five, 10, 25, or 250 years into the future. What happens when we make a building 10 stories tall, or change it from a triangular prism to a cylinder? What impact will that have on the people, plants, wildlife, and traffic?

I’ve seen brilliant examples of this where people are deciding where to site wind farms. Where’s the wind? What are the impacts on wildlife? What are the impacts on other crucial aspects of the ecosystem, like worms?

Unlike traditional mapmaking, which is mostly about documentation, geodesign actually informs the design process and affects outcomes of what is built, preserved, modified, or otherwise changed in the real world. It gives us the chance to interact with the future through turning the knobs and seeing what happens. We can watch these things occur in front of us, and design better strategies for better outcomes. It lets us test hypotheses and make near-term decisions that will have long-term consequences.

Most importantly, it lets us combine the many disparate aspects of our future—and then put ourselves into the picture. u I think there’s a reasonable chance that if we show most people a convincing view of their future, both good and bad, and help them understand the story of how it could be changed for the better, we could change the course of society—and the fate of the Earths.

Storytelling for the future

One of the best ways to get someone to listen to what you have to say is to tell a story.

Storytelling is the world’s oldest profession and is fundamental to the human experience. It’s integral to how we’ve built our civilizations, and can be used to make ideas memorable, compelling, and inspirational.

In my view, every great leader is also a great storyteller, whether that was Winston Churchill, John F Kennedy, or Steve Jobs. They used their storytelling skills to drive home their messages and inspire people to follow them.

For example, when Steve reveled the new super-slim MacBook Air in 2008, it wasn’t with a giant production as often seen at these events. No dancers, no pyrotechnics, no computer animation, no multimedia, no special effects. No, he did it by simply holding up a simple manilla envelope. Then in one effortless motion, he slid Apple’s latest sleek and beautifully crafted laptop out of it, and balanced it on his fingertips.

At a time when laptop computers mostly had all the slender elegance of a cement block and the intrinsic beauty of a gray plastic cafeteria tray, this memorable reveal was greeted by looks of amazement. I was in the audience, and there were audible gasps, smiles, and then thunderous applause. Followed by huge economic success.

He didn’t have to say one word to explain what made this product compelling. That simple five-second theatrical moment said more than words ever could.

For a lot of people in this visual, media-saturated world, seeing is still believing—and critical to understanding. If we can actually see things happening with our own eyes before they happen in the future, and appreciate the consequences of those actions, we might just change how we act in the present.

Geodesign allows us to do that. It will empower us to create a superior future. It will harness the strength of our explorers, designers, academics, inventors, scientists, storytellers, public officials, and the people of the world. It will enable a new kind of collaboration and future-seeing in a way that will allow development of the built world to better exist in harmony with the natural world. It’s a way to bring the future into the present—and to look at many different futures. If we’re going to change the world for the better, we have to give people the ability to see and to believe how we can actually do it.

So what took so long? Why is geodesign only now becoming a reality?

It takes time for various technologies to evolve to a state of maturity—but it takes an even longer time for people from very different disciplines to learn to speak each other’s language. Not insignificantly, it’s also taken time for us to realize the damage we’ve done to our world—and it takes time for people to believe it.

I’ve never met someone who actively wants to harm the environment. It happens because they either don’t know any better, or have self interest that overrides their sense of civic responsibility. In the first instance, if we can educate people about viable and practical alternatives, they will often be happy to modify their behaviors. In the second, techniques such as government subsidies and incentives can help—and when they don’t, instituting policies, laws, and strong tools for enforcement can work wonders.

And geodesign helps us achieve both.

It’s really happening, and it’s happening now. I believe in the fruits of our collective labors. I believe in the process of educating our appointed leaders and policymakers of the possibilities and benefits of using the principles of storytelling. With them, we can truly empower those in power to create a better world for our kids, and for many, many generations to come.

Now we all just need to find the will to get it done.

This article was adapted from a speech Bran Ferren gave at the Global Exploration Summit in Lisbon, a gathering of The Explorer’s Club’s most intrepid members.