World health leaders warn the world is dangerously unprepared for a pandemic

In October 2014, a man died of Ebola in Dallas. Two of the nurses who treated him contracted the virus. Days later, a physician returning from West Africa was diagnosed with Ebola in New York City. Although the authorities said there was no reason to stock up on hazmat suits, people freaked out: Was this the beginning of a deadly epidemic in the US?

In October 2014, a man died of Ebola in Dallas. Two of the nurses who treated him contracted the virus. Days later, a physician returning from West Africa was diagnosed with Ebola in New York City. Although the authorities said there was no reason to stock up on hazmat suits, people freaked out: Was this the beginning of a deadly epidemic in the US?

As we know, it wasn’t. But it sure inspired the US government to invest in systems to make sure it never does: An Ebola czar was appointed, and billions of dollars were spent on research and to support the relief effort in West Africa.

It was a pretty typical reaction for a government: From Zika to bird flu, countries only mobilize to protect themselves from infectious diseases after they arrive—an approach that isn’t going to do very much in the case of a serious, fast-spreading epidemic.

In fact, the world is so woefully unprepared for the potential of a worldwide illness that a group of concerned and prominent political leaders have joined forces to form the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, an independent body working to face down such emergencies. Among those on the board are former Norwegian prime minister and World Health Organization (WHO) director general Gro Harlem Brundtland, Unicef director Henrietta Fore, and International Federation of Red Cross secretary general Elhadj As Sy.

In its first annual report on Sept. 17, the group analyzed just how ready the world is for a medical emergency. The findings aren’t encouraging. If an epidemic as serious as the 1918 Spanish flu were to emerge today, it would take about 36 hours to become a pandemic, and it would kill up to 80 million people.

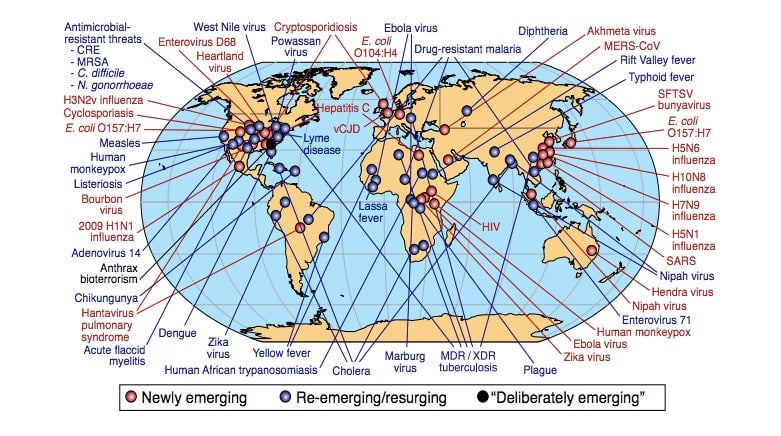

To give a better sense of the seriousness of the threat, the report begins by outlining a few of the ongoing crises in the world. There are emerging threats like Zika or human monkeypox, re-emerging threats like measles, or—perhaps most scary of all—deliberately emerging threats like bio-terrorism. It’s not a reassuring image:

While we think of pandemics as catastrophic, apocalyptic movie-like scenarios that are remote from our daily life, the truth is we already experience them routinely—for instance, with the yearly flu. The flu demonstrates just how easily disease can travel across the world, and how complex it is to contain the spread once it begins.

Between 2011 and 2018, the WHO tracked 1,483 epidemic events in 172 countries. What is even more worrying is the likelihood of a new disease emerging. “Changes in the environment are exposing the animal reservoir [of pathogens] to humans,” Victor Dzau, president of the US National Academy of Medicine, told Quartz. Deforestation, for instance, brings more wildlife in contact with human settlements, exposing people to more diseases transmitted by animals. Changes in climate also help spread disease, for example by promoting mosquito breeding.

In the face of all this, the global health community is far from ready. “For too long, world leaders’ approaches to health emergencies have been characterized by a cycle of panic and neglect,” Brundtland said in a statement presenting the report. Instead, action to face potential pandemics should be systematic, and begin with investment in strengthening the health system of the poorest countries.

The importance of making a health system more resilient can’t be overstated: Nigeria, for instance, was able to contain the spread of Ebola during the West African epidemic in a way Sierra Leone or Liberia lacked the means to, only because the Nigerian health system had some level of reliability. Similarly, when the virus crossed into Uganda from the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2018, it was quickly contained. And as poorer countries are more vulnerable to epidemics, it’s important for wealthier ones to support their efforts to stop them—even just out of self-preservation.