You can thank this mid-century cat photographer for your favorite cat memes

“Why do you have a giant book of cat pictures in your office?” asks my colleague, intrigued. To which there is only one answer: “What if the internet goes down?”

“Why do you have a giant book of cat pictures in your office?” asks my colleague, intrigued. To which there is only one answer: “What if the internet goes down?”

Some Brits are stockpiling canned tuna and freezing bread in case of a no-deal Brexit. I’m just making sure I have a decent supply of adorable kitties for when the climate catastrophe/nuclear apocalypse/political meltdown (strike as appropriate) eventually isolates the British Isles from the rest of the world.

And you can too, thanks to Taschen’s magnificent Cats, a 300-page extravaganza of photographs by Walter Chandoha.

Chandoha is not an Instagram catfluencer or rising TikTok star. He was here before all that—long before. Born in 1920, he developed a keen interest in photography in his high school years, and soon after started working as an apprentice with an advertising man in New York City. He was drafted into the army during WWII and served as a combat photographer, where he learned (channeling his future subjects) “the value of thinking on your feet.”

One winter night after the war, on the way home from university, he found a kitten shivering in the snow and took him home. The kitten, like most kittens, was a silly little fellow who would run around the flat “like a man possessed”—and Chandoha, like millions after him, grabbed his camera and started shooting.

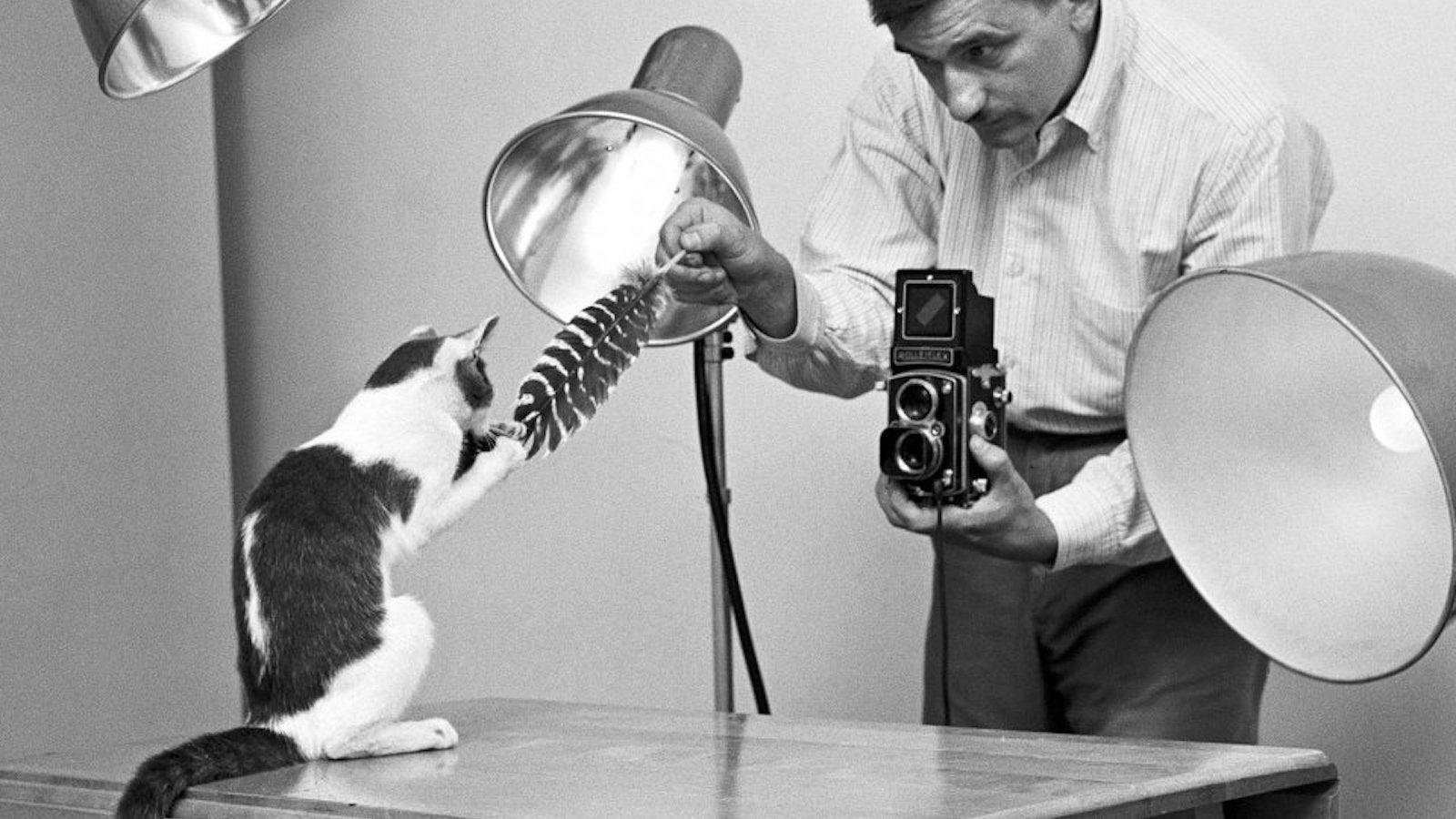

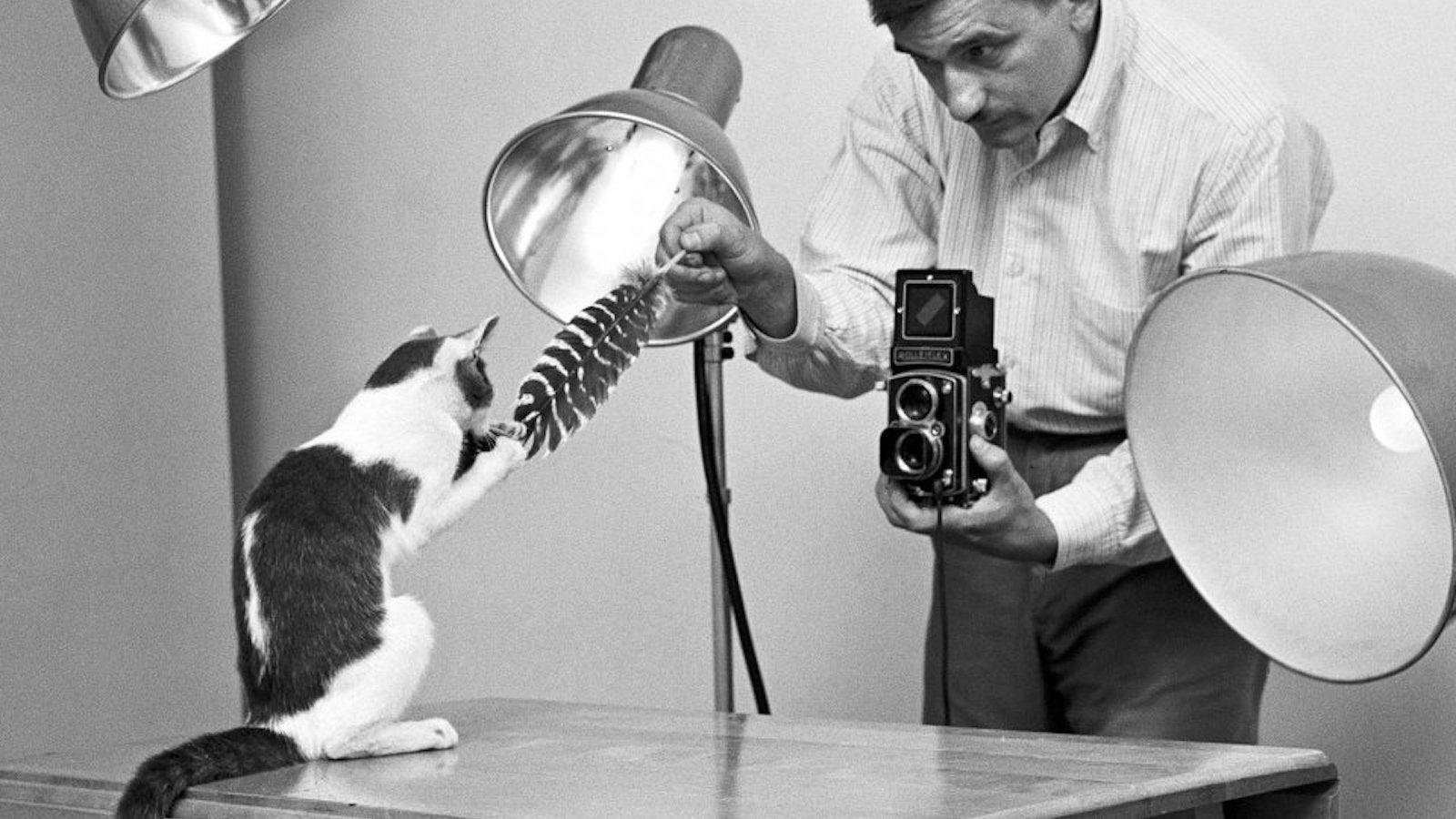

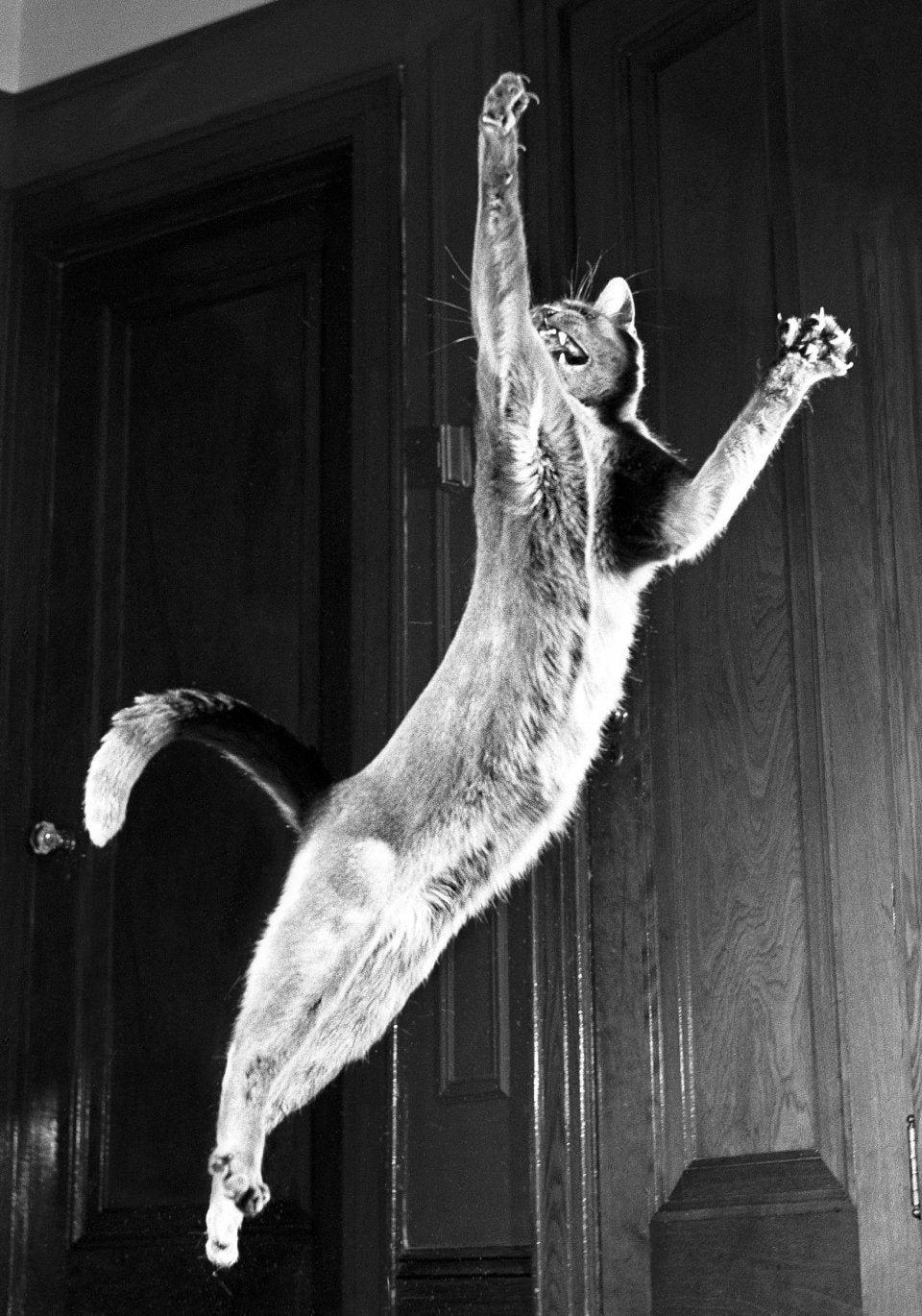

Thus was born a lifelong obsession with—and a lucrative career of—taking pictures of cats. Over the course of his cat-focused career, Chandoha has taken cat pictures in every imaginable setting: soft-focus studio shots, artful candid ones, edgy street pics, cats on their own, cats with dogs, with bunnies, with duckies, with babies, with other cats. Cats in New York, cats in New Jersey, cats in Italy. One of the most interesting pictures in the book is a behind-the-scenes shot, in which Maria, Walter’s wife, styles a cat on a stool while his daughter directs the light and his son looks on as he shoots. This is a serious business, and the whole family gets involved.

“Fashion has Helmut Newton, architecture has Julius Shulman, and cat photography has Walter Chandoha,” reads the blurb on Taschen’s website. “He’s the Richard Avedon of cat photography,” said the colleague who gave me the book. Some of the photographs—like a surreal one of 11 cats all sitting peacefully and obediently looking in the same direction—bring to mind the baroque set pieces trademarked by Annie Leibovitz.

Yet such contemporary comparisons are almost beside the point. In the world of cat photography, there is Walter Chandoha, and there is everybody else.

He was the cat-photo progenitor. Back in 2007, the canonical lolcat had to be uploaded from a digital camera to your computer and only after that to the internet, where they were emblazoned with Impact typefaces. Then Steve Jobs introduced the world to the iPhone, and in the past decade nearly 4 billion people have acquired devices that they use to access the internet—and to fill it with cats.

Today, we are all Walter Chandoha. Just last month a clip dubbed “the best TikTok ever” went viral—a clip of Ed, a gormless Canadian cat, being shimmied about by his owner to the tune of “Mr Sandman.”

On the one paw, the spate of cats on the internet is what free-market capitalism is all about: We have more cats now than ever before, and in more formats, too. The abundance of cat memes today matches our appetite for them, and modern technology gives us both a depth and a breadth that was unavailable in the pre-democratic, SLR era of photography.

But on the other paw, perhaps the scattershot nature of our visual kitty culture has made us less patient—less willing to sit, as Chandoha did, for hours waiting for the perfect shot, the perfect expression. We no longer pause to consider the perfect beauty of the nameless cats of Instagram in the same way we devoted ourselves to Longcat or Grumpycat or even Cyancat. The fur has lost its sheen.

But on the third and fourth paw, maybe there is no tension here at all. The beautiful thing about progress is that it allows us to have it all: the silliness of Ed the Canadian cutie and the greed and bad grammar of the cheezburger lolcats and artful labor of Chandoha’s art. Just as Vogue and Vanity Fair continue to exist in a world of blogs and influencers, so too will analogue kitties live alongside their digital counterparts.

With Walter Chandoha. Cats. Photographs 1942–2018, Taschen provides a timely (and also heavy and rather pricey) reminder of the fact that there are enough cat photos to go around in all their forms: chonks, megachonks, and oh lawd he comin’s alike.

Moreover, what if the internet does indeed go down? Best to be prepared.