How Neil Young’s failed anti-streaming business helped the music industry

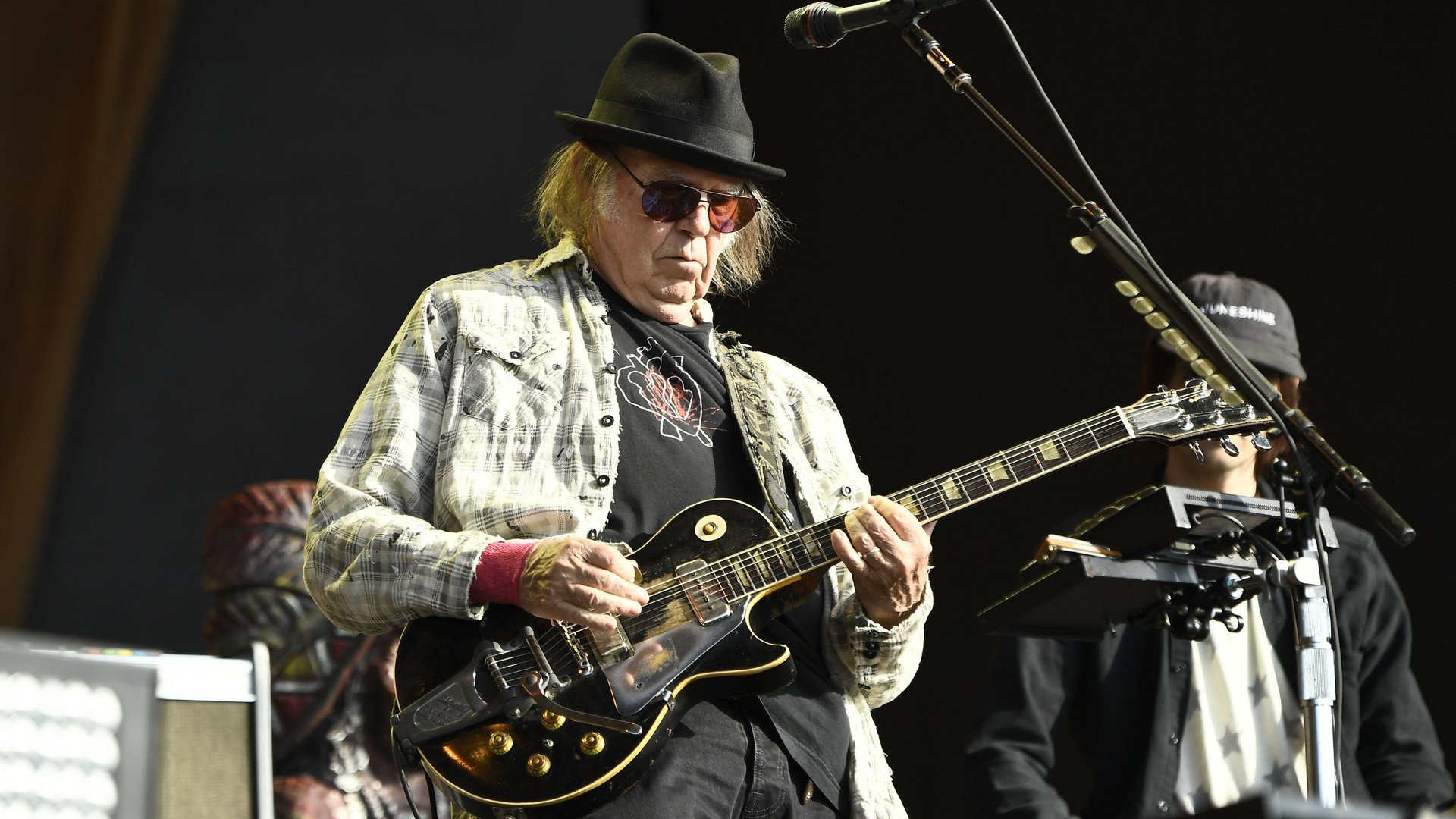

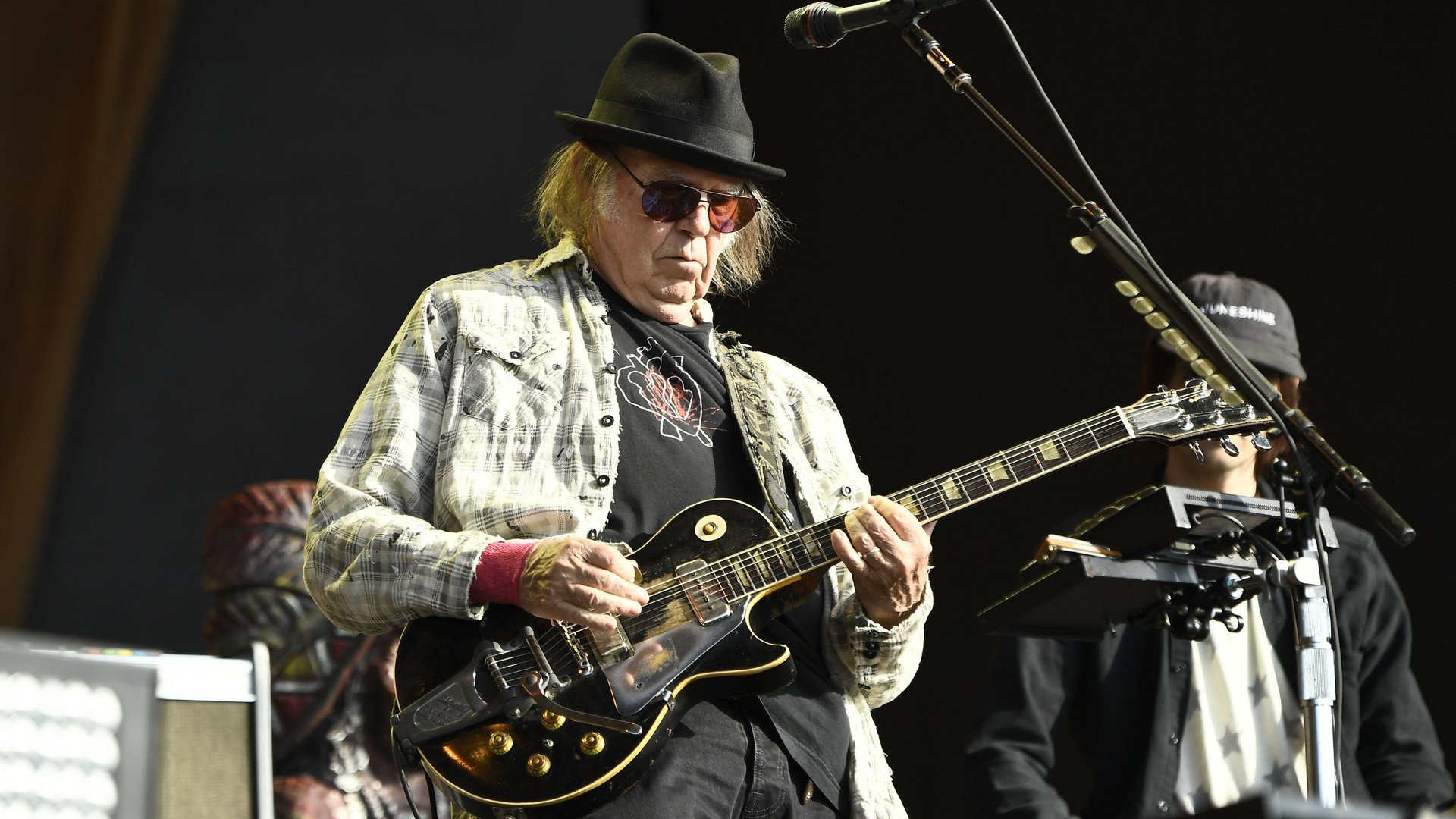

Toward the end of music legend Neil Young’s recent memoir, he makes an admission: “I was wrong.”

Toward the end of music legend Neil Young’s recent memoir, he makes an admission: “I was wrong.”

The book, To Feel the Music: A songwriter’s mission to save high-quality audio, is something of a postmortem on the musician’s high-resolution download service which folded in 2017.

PonoMusic, Young’s short-lived company (it lasted five years) was something of an anti-iTunes, offering uncompressed, studio-quality downloads and a trademarked player that “sounded like God,” (although some reviewers disputed this assessment).

PonoMusic was also anti-streaming. “My aversion to streaming was not only because of its effect on music quality,” he writes in his book, “but because of how poorly record companies and streaming deals treat the artists.”

Young’s failure to embrace that technology early on—even as consumers abandoned downloads in droves for Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music—was, in his words, “one of my biggest mistakes.”

To Feel the Music is co-authored by Young and PonoMusic’s former COO (now CEO of the Neil Young Archives) Phil Baker. It gifts readers with a sort of roadmap to help navigate the complex music industry—mostly in terms of where we should not go, via their own failures.

Young and Baker alternate chapters, with Baker’s under-the-hood tech analysis supplementing Young’s eager, straight-shooter narrative. Together they describe familiar startup issues, like revolving CEOs and production setbacks, chronicling Young’s seven years as a scrappy Silicon Valley entrepreneur.

A lot has happened in the business since I first reported the news of PonoMusic’s launch in 2012. After the company shuttered, Young has since renewed his focus on audio quality with his own high-resolution streaming service, Xstream, as well as the Neil Young Archives website, where fans pay $1.99 a month for access to his deep catalog.

Young and the PonoMusic team made some big mistakes. But Young also did a lot for progress in the music business. It was his concept that got the industry rolling on high-resolution music, even though it also indirectly unraveled his own company.

To take a page out of Young’s book, for lack of better expression, people looking to survive and innovate in the industry would be wise to pay attention to these three major blunders in particular, if they want to avoid becoming the next PonoMusic.

Don’t dismiss the value of an industry trend

As Young told an investor early on, “There’s nobody who can stream the true quality of music.” The way he saw it, streaming companies couldn’t afford to offer high-resolution recordings, and consumers couldn’t afford to buy them anyway. But, as he concludes in his book, he was wrong. Young, who turns 74 in November, has long crusaded against inferior audio, arguing that streaming deprives music fans of a true listening experience. But that’s where most people get their music today, with 61 million paying subscribers in the US alone. And while services like Deezer and Tidal introduced users to high-resolution streaming, PonoMusic continued to offer only downloads.

Young’s fight to rescue the sound of recorded music dates back more than 50 years. Upon listening to his first solo album in 1968, he demanded that the record company re-release it; it had mixed Neil Young using tech designed to enhance stereo recordings played on mono equipment. Young hated it.

From this disgust came his vision. Young quietly began developing PonoMusic in 2010 and filed several applications for trademark names, including “21st Century Record Player” and “Thanks for Listening.” Warner Music Group was the first record company to convert its thousands of albums for the project, and also invested $500,000. Sony and Universal soon followed. Young secured the endorsements of dozens of fellow musicians, including the late Tom Petty, who claimed PonoMusic “would save the music business.”

Steve Jobs was not so enthusiastic. Before he died in 2011, Apple’s CEO “had no interest in hi-res for his products,” Young writes. “He told me his customers were perfectly satisfied with MP3 quality.” (This August, the company launched its high-resolution streaming offering, Apple Digital Masters.)

In 2013, Young found his CEO in John Hamm, a tech veteran who swiftly assembled a team, budget, and product schedule. PonoMusic’s engineers and developers came from places like Apple and Google, and Hamm set them up in a third-floor office in San Francisco.

Don’t fire your CEO when the stakes are high

High-resolution players and services already existed, but were mostly unaffordable and catered to a niche market. What would set PonoMusic apart was its digital-to-analog conversion software, developed by UK-based Meridian Audio. That crucial tech would restore brittle MP3s to the warm clarity of the original studio recordings. Everything depended on it. But once the PonoMusic players were manufactured and ready to go, two years’ worth of discussions with Meridian stalled and never materialized.

Hamm found another audio engineer and PonoMusic was saved. But as the team found, Young’s fame was taking the project only so far; attracting investors was a slog. By March 2014, PonoMusic was running out of money and turned to Kickstarter.

PonoMusic became one of Kickstarter’s most successful campaigns, with pledges of $6.2 million from 15,000 backers. This amount “equated to 2.6 million real dollars,” Baker writes, adding that offering the player at $300 was a mistake. “It gave us too little margin to effectively sell at retail and barely enough profit to pay for all of the development.”

Before those players were shipped, in late 2014, Hamm was fired. PonoMusic’s board named its attorney as CEO, after he convinced Young that Hamm was trying to take over the company. But, as Baker writes, “Neil now believes that losing Hamm was a pivotal moment for the company and regrets what happened.”

Don’t negotiate for too long with a partner (they may leave you for Tidal)

At the 2015 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, critics got their first look and listen to PonoMusic and served up mixed reviews.

That year, the streaming space grew cluttered, if not downright incestuous: Apple bought Dr. Dre’s Beats Music, whose platform was acquired from a former PonoMusic consultant; Apple Music was born from that deal. Meanwhile, Jay-Z launched Tidal, a high-resolution streaming service that runs on the software developed by none other than Meridian, PonoMusic’s former partner. (Young’s catalog streams on Tidal and other platforms.)

Young and the team were blindsided by what happened next, in mid-2016. PonoMusic’s download store operator, Omnifone, alerted Baker that the company had a new owner: Apple. The PonoMusic store was shuttered days later, which effectively ended Young’s venture.

The unexpected Apple purchase and shutdown of the site was insurmountable. But what ultimately doomed PonoMusic was Young’s dismissal of streaming until it was too late.

More than anything, To Feel the Music is a case study in business hindsight. Young’s initial vision was too stubborn; he was stuck in the past. He refused to see the value in the changing technology, and he tried to yank the industry back, and force it to stay there, in the name of uncompromising quality.

But just this week, Young signaled that the future for quality audio sound is bright.

When Amazon announced its forthcoming high-quality streaming service Amazon Music HD, he proclaimed the company is “the leader now” on his website.

“Now it will be possible for you to feel all my records the way I made them, in their highest resolution,” he wrote. “I always knew this day would come!”