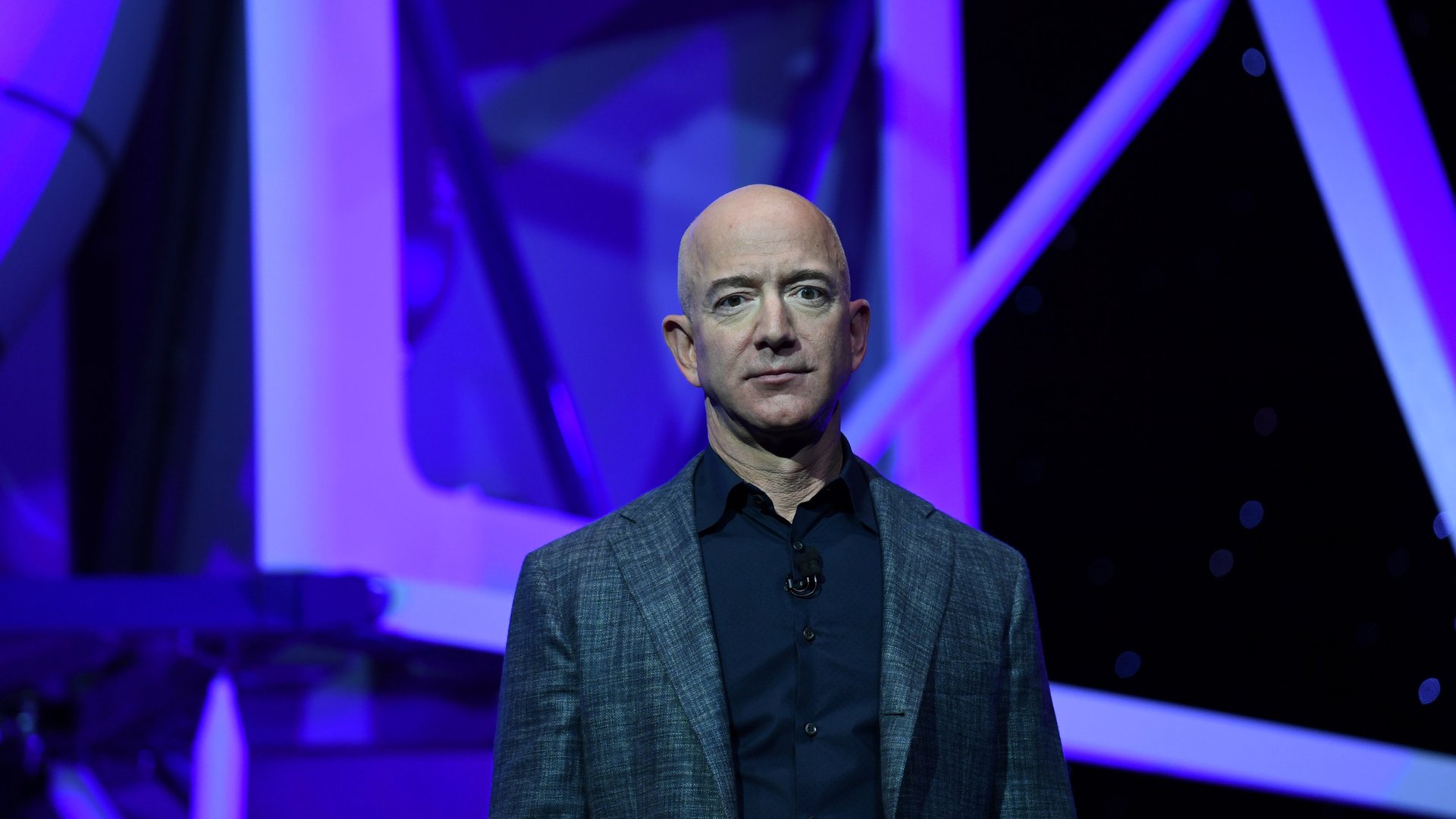

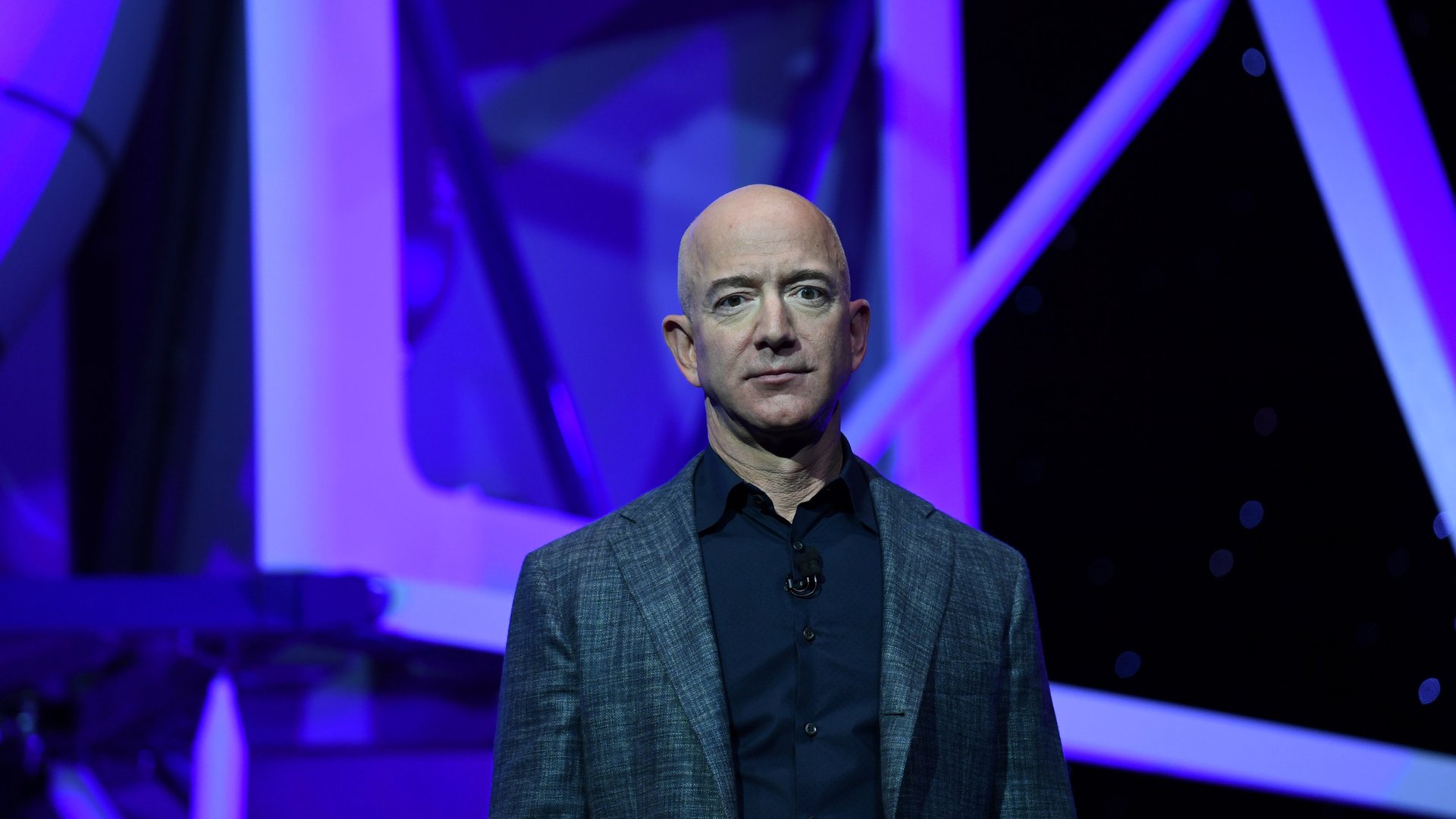

Jeff Bezos wants the US military to think bigger in space

The US military’s plan to buy rockets is missing major trends in the space industry, according to Blue Origin, the rocket-making company started by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

The US military’s plan to buy rockets is missing major trends in the space industry, according to Blue Origin, the rocket-making company started by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

In media briefings yesterday (Sept. 24), Blue Origin CEO Bob Smith laid out the rationale behind the company’s challenge to the US Air Force’s National Security Space Launch program.

The Air Force intends to tap two rocket-makers to fly five years worth of launches, with contracts likely worth more than $1 billion annually, split 60-40. Besides wanting redundant options, the Air Force believes that the launch market can only support two private-sector providers.

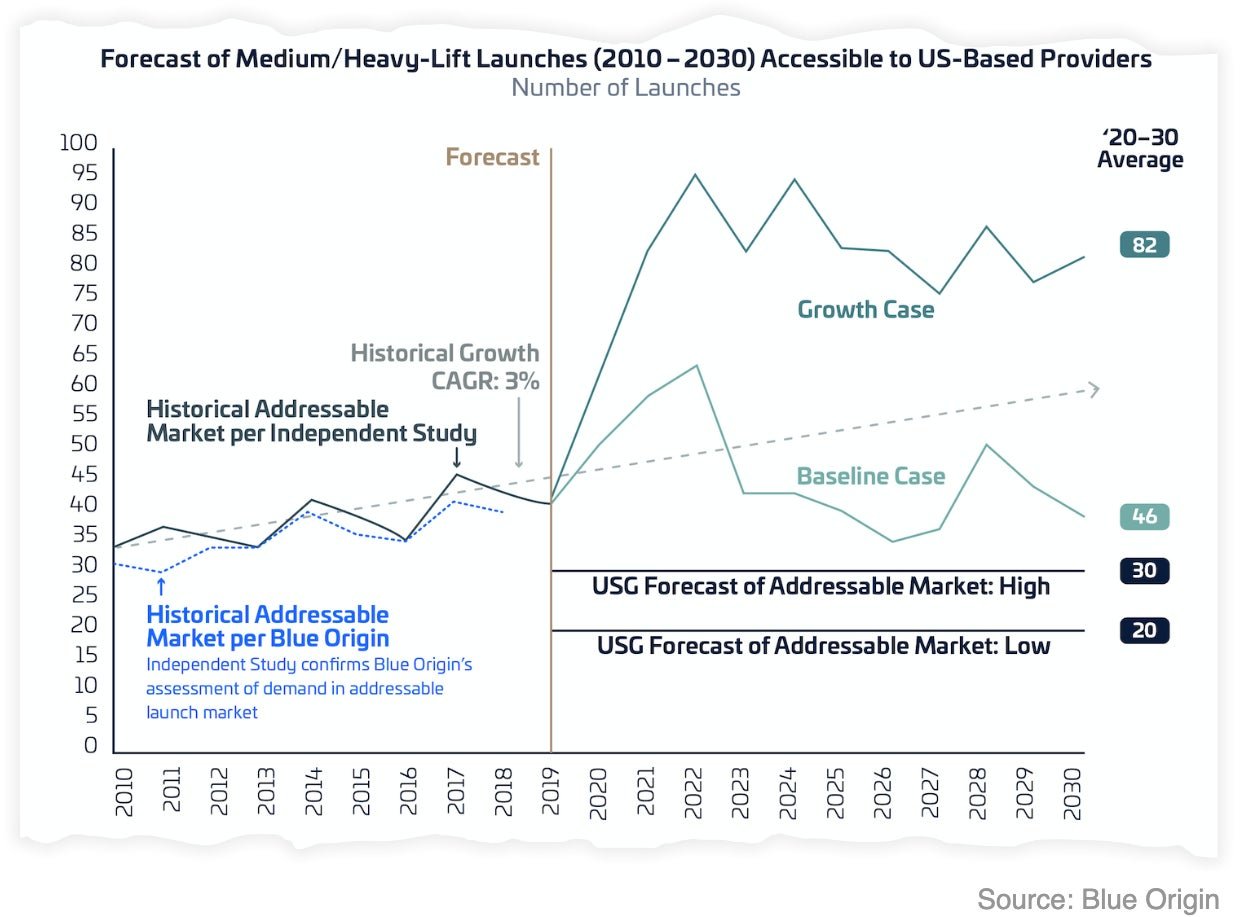

That’s just not true, according to a forecast commissioned by Blue Origin, which believes the military can safely choose three or more providers to provide a more competitive and innovative environment for the US space industrial base.

The company hired an unidentified consulting firm 1 to forecast the number of launches that US rockets could compete for in the years ahead. While the Air Force expects a high of perhaps 30 launches a year for the next decade, Blue Origin says its baseline case is for 46 launches annually.

“The fundamental message is that the addressable market… for national security is only about 20% of the overall market,” Smith told Quartz. “So it really is backwards to think, ‘what do we need for national security?’ and then limit what the launch vehicle options are. A launch vehicle company that is commercially viable will provide better value and overall better pricing.”

Though Blue Origin is confident in its bid, industry observers believe they are likely to miss out on a contract, falling behind the current incumbents, the Boeing-Lockheed Martin joint venture United Launch Alliance and Elon Musk’s SpaceX. Executives at Blue Origin, which plans to debut its orbital New Glenn rocket in 2021, fear they could be locked out of bidding on military business for as long as decade.

“I can be a very capable commercial launch provider winning up a slew of business and providing great value, but unless you actually have invested in that DOD (Department of Defense) specific infrastructure and those DOD specific certifications, those commercial launch providers literally cannot go compete for that business,” Smith said.

Why does the demand from private satellite operators and NASA matter to the US Air Force? The reason dates back to when the military began purchasing launch services from private companies in the 1990s.

At the time, the prices set by Lockheed and Boeing were based on the expectation that both would earn significant revenue from private launches. But an expected satellite boom didn’t pan out amid the collapsing tech bubble, and the two companies formed a subsidized monopoly, United Launch Alliance (ULA), arguing it was the only way to keep churning out new rockets. The monopoly led to enormous price hikes for the government, until SpaceX arrived in 2014 and sued the Air Force for the right to bid on launches. (SpaceX is also challenging an earlier phase of this process, when the Air Force gave development contracts to the other bidders.)

The government doesn’t want to base its plans on rosy projections again, hence the emphasis on commercially viable companies. But it’s hard to define what that means. ULA, for example, is largely reliant on government business, and would be difficult to sustain without the Air Force contract. Losing the bid would lead ULA’s two parent companies “to evaluate what that meant for the future of United Launch Alliance,” the company’s chief operating officer said earlier this month.

Asked outright if ULA (for whom Blue Origin is building a rocket engine) or aerospace contractor Northrop Grumman are commercially viable, Smith was diplomatic, saying, “one of the fundamental problems is that we have, again, the government trying to estimate and decide what commercial viability is.”

A key part of Blue Origin’s equation are proposals for satellite mega-constellations flying in low-earth orbit. Companies like SpaceX, OneWeb, Telesat, and Amazon have all proposed launching thousands of new communications spacecraft. Those launches make up about 35% to 40% of Blue Origin’s forecast “growth case,” which assumes the deployment of two large satellite constellations and two smaller ones. Blue Origin’s baseline case assumes just one of the mega-constellations alongside smaller networks.

The past may again be a factor here for the US Air Force, which will recall that massive satellite constellations like Teledesic helped drive those 1990s launch forecasts—before they failed.

“History doesn’t have to repeat itself,” Smith said. “The fundamentals of space have changed over that period of time. We rely on space every day of our lives. Space is now a [militarily] contested area. We do have a renewed emphasis on [space] exploration. All of those things are combining [in] a need for a proliferation of capable launch providers.”

Smith didn’t answer when asked if Blue Origin executives had been consulted when Amazon announced plans for an ambitious satellite network this spring.

“One of our current satellite customers is Telesat and… we’re going to be able to provide them great value because [of] our superior heavy lift capabilities and larger fairing,” Smith said. “We anticipate that there’ll be other constellation providers that will also sign up for new planned launches.”

Whether one of those customers will be the US Air Force will depend on several factors, including Blue Origin’s lobbying push, the on-going legal challenges, and Congress potentially weighing in during the annual defense spending bill. Final decisions are expected in June 2020, though changes to the process could push that date back.