Space-based data on polluters is improving—and Wall Street is taking notice

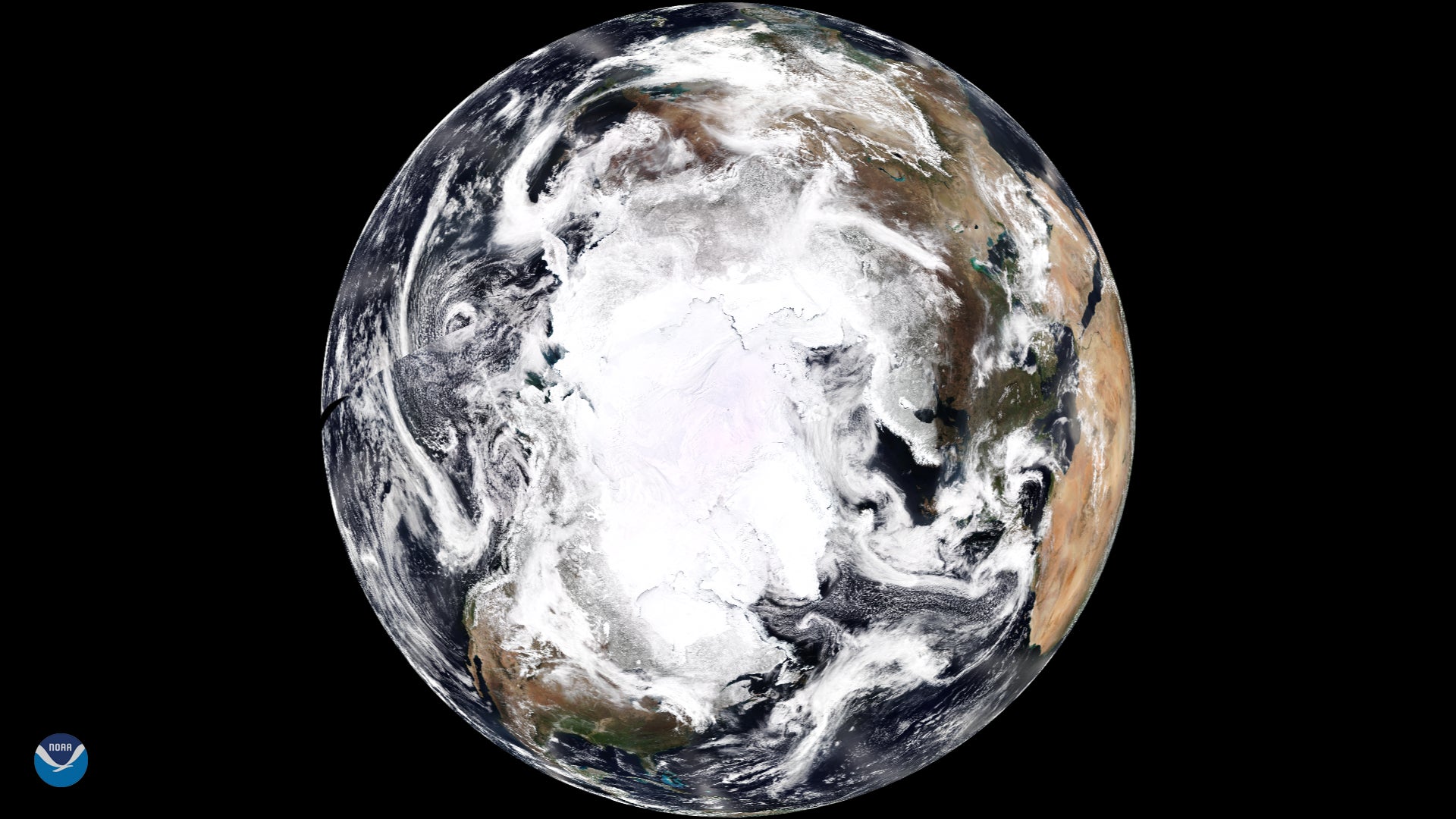

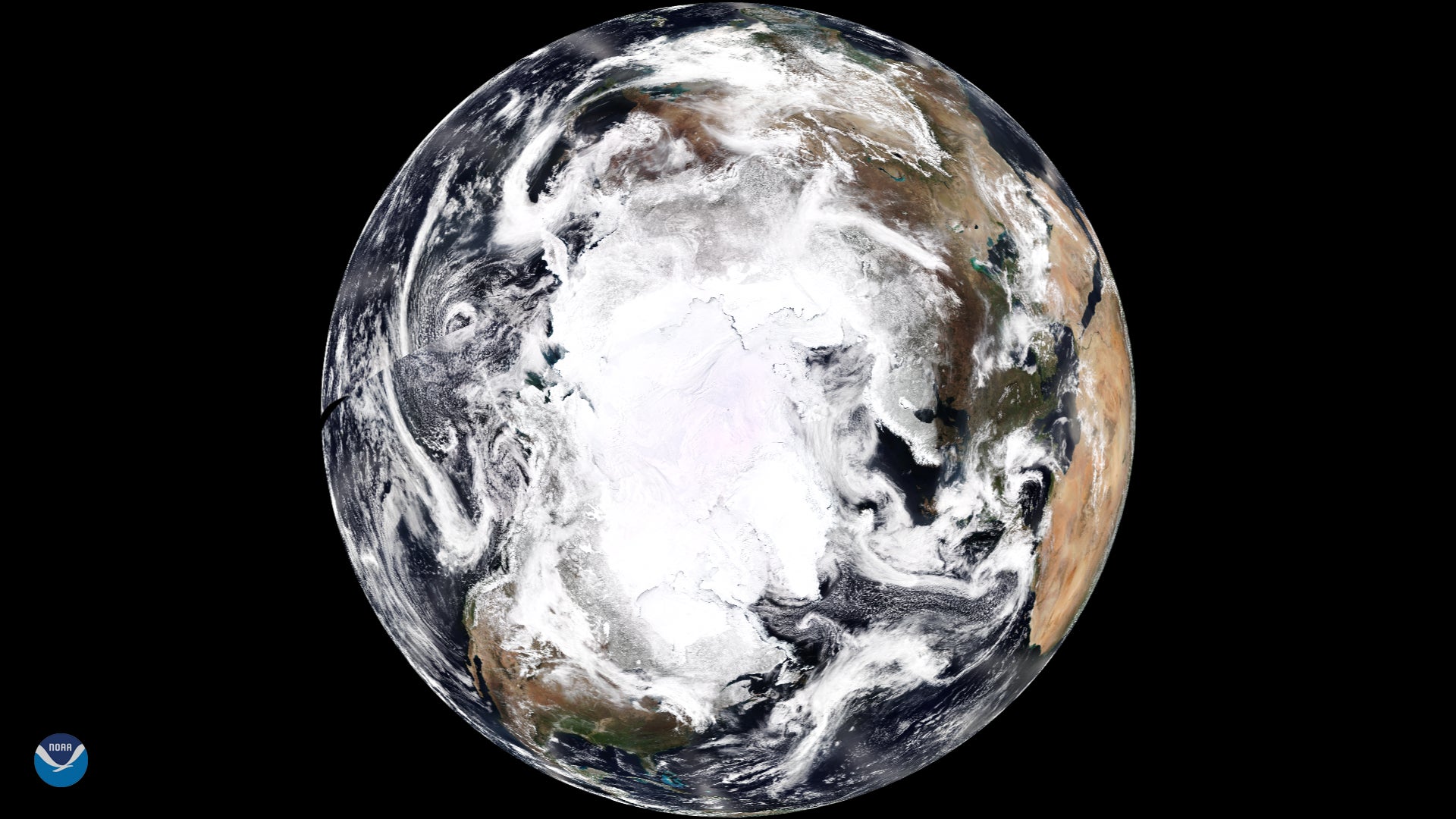

A few miles above us, more than 200 tiny satellites circle the globe, collectively taking a snapshot of Earth’s entire landmass every day. Studded with cameras and sensors, each Dove, as the devices are known, peers down on a rapidly warming planet. The flock’s owner, Planet Labs, promises one day it will use its orbiting hardware to precisely monitor greenhouse gases—and ultimately aid in reducing them.

A few miles above us, more than 200 tiny satellites circle the globe, collectively taking a snapshot of Earth’s entire landmass every day. Studded with cameras and sensors, each Dove, as the devices are known, peers down on a rapidly warming planet. The flock’s owner, Planet Labs, promises one day it will use its orbiting hardware to precisely monitor greenhouse gases—and ultimately aid in reducing them.

California says it is now planning to use those Doves to monitor wildfires in the state, as well as coal plants around the world. The effort, part of an initiative it’s partnering with Planet on called Satellites for Climate Action, will help anyone with the data understand how the world is advancing toward a low-carbon future.

The effort is the latest iteration of California’s plan to launch its own satellite (or satellites) to track greenhouse gases such as methane and CO2, even as the Trump administration attempts to kill off space-based climate monitoring. Last September, then-governor Jerry Brown said at the conclusion of the Global Climate Action Summit: “With science still under attack—we’re under attack by a lot of people, including Donald Trump—and with the climate threat growing, we’re going to launch a satellite—our own damn satellite to figure out where the pollution is and how we’re going to end it.”

California’s effort may mean the beginning of precise regulation (and public shaming) for high-emitting firms. It’s also a new worry for investors. Cheap, global, real-time monitoring for anyone who wants it can give governments and advocacy groups a new way to target big polluters, notes Ned Harvey, managing director of industry and heavy-duty transport at the Rocky Mountain Institute. “Top-down measurement is coming,” he says. “Now it’s bits and pieces. Within 10 years, we’ll have really large, clean data sets with no question of what’s good and bad.”

Harvey predicts civil society and governments will have access to nearly real-time data of the globe, allowing them to hold countries and companies accountable for emissions. And if regulators don’t, he argues, markets will. Data on methane plumes or polluting operations can be turned into financial risk signals. “Wall Street can’t ignore that fact,” he says. “I’m far more optimistic that companies and investors will understand and react because the downside risk is so huge for them.”

Carbon disclosure has already been embraced by most European countries, says Denis Duverne, who chairs the board of directors at the insurer AXA, and climate exposure is on its way to becoming a standard risk factor for investors. AXA already measures the warming potential of its $550 billion investment portfolio, and “we engage with companies that we believe are not making necessary efforts,” he notes.

That “engagement” isn’t always favorable. After AXA and other financial institutions divested from coal companies in recent years, many soon went out business due to their dwindling access to capital and uncompetitive coal plants.

Fallout for other sectors could be huge. A report commissioned by the Principles for Responsible Investment, a UN-affiliated investor group managing $86 trillion, concluded that by 2025 an “inevitable” policy response to climate change would lead to a huge devaluation for companies in energy, agriculture, transportation, and other sectors by 2030. With 90% of firms not yet pricing in carbon, the report says, financial markets essentially betting against government action could be in for a huge correction.

That gives startups a big early incentive to become the global accountant for the market. Images of Earth’s atmosphere from space are now flowing into databases around the world. Descartes Labs, which offers satellite imagery analysis, is one of the ventures. It’s refining remote sensing data into insights. Last month it teamed up with New Mexico to monitor methane emissions from the Permian Basin, a massive oilfield spanning 86,000 square miles (220,000 sq km) in the US Southwest. The state plans to generate 100% carbon-free electricity by 2045, but to do so, it needs to plug methane leaks and identify emissions sources almost down to the well.

Today, that’s not possible. Satellites must analyze data through the thick, turbulent atmosphere. Aerial surveys are precise, but expensive. Ground sensors are still needed. Mark Johnson, founder and CEO of Descartes Labs, says the firm is experimenting with combining different data sources to understand emissions.

At the moment, Descartes Labs relies on orbital data from the satellite Sentinel-5P, developed by the European Space Agency and dedicated to studying the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide sources are hard enough to measure, says Johnson, but the science on emissions such as methane is still emerging. Analyzing a 100-mile-high moving column of air is still beyond the best technology. Subsequent Sentinel missions should deliver better data.

But Johnson believes even the best hardware and software for detecting gaseous methane from drilling leaks wouldn’t be enough. Data sharing and sheer costs are major hurdles since piecing together a real-time emissions map from any single source alone, especially satellites, could prove impossible.

“We are far away,” says Johnson. “It’s something everyone wants…but there’s no silver bullet.”