The best slide deck about climate change comes from a Danish-Icelandic artist

The recent UN Climate Action Summit in New York was a marathon of presentations (pdf) by scientists, activists, and policy wonks sharing ideas on how to save our beleaguered planet. But of the many who spoke, it was Olafur Eliasson, a celebrated Danish-Icelandic artist, who had the most arresting slide deck.

The recent UN Climate Action Summit in New York was a marathon of presentations (pdf) by scientists, activists, and policy wonks sharing ideas on how to save our beleaguered planet. But of the many who spoke, it was Olafur Eliasson, a celebrated Danish-Icelandic artist, who had the most arresting slide deck.

The recently appointed UNDP goodwill ambassador had, in a sense, been accumulating material for his Sept. 26 lecture for years. His three-decade career has surfaced the marvelous yet overlooked qualities of light, water, and air. With his sensibility shaped by the dramatic vistas of Iceland and Denmark, his oeuvre is evidence of how public art can foster “a felt understanding of the challenges at hand,” as he puts it.

Eschewing the hard-hitting bullet points, pithy slogans, and data graphics of many slide decks, Eliasson’s presentation, like his art, was a masterclass in eliciting an audience’s awe and curiosity.

He began with images of “Ice Watch,” a project that involved him working with a geologist and transporting 12 glacial ice blocks from outside Greenland to the center of Paris. Timed for the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference, the “sculptures” were arranged in a circle to symbolize how little time we have to act on climate change. It was a poetic spectacle, accompanied by a report (pdf) about the installation’s CO2 impact.

“I think a lot if people realized that they were looking at 15,000, maybe 25,000 years of frozen water,” he said, noting that the act of touching the ice might result in a deeper concern about the rapidly disappearing Greenland ice caps and sea level rise. “If you put your ear to the glacier, you can actually hear many sounds,” Eliasson said, referring to the popping of air bubbles as the ice melts. “These micro-relationships are interesting. To take all the data, news, and scientific papers and turn it into something you can touch is I think incredibly affective.”

Eliasson also discussed his career-making 2003 exhibition at London’s Tate Modern. The “Weather Project,” an atmospheric installation that bathed the museum’s cavernous Turbine Hall in amber light, drew more than a million visitors during its five month-run. The most interesting result of the project, Eliasson said, was hearing the range of interpretations it conjured:

Some people compared it to being in a peaceful Japanese garden, while others thought the world is ending. It’s interesting that they were having this experience together, but seeing different things. Where in our societies can we find safe spaces to interact with people who we aren’t synchronized with?

Eliasson has a lifelong fascination with the physics of water. “Time and water are things that we don’t see in postcards, books, and computer renderings. Instead of thinking about it, it’s different when you can physically move through it,” he said. This idea runs through his series “Waterfalls,” towering cascades of water recreated in unexpected locations such as the Brooklyn Bridge and the Gardens of Versailles. The intent, he said, is to “make water explicit” so we might not take it for granted.

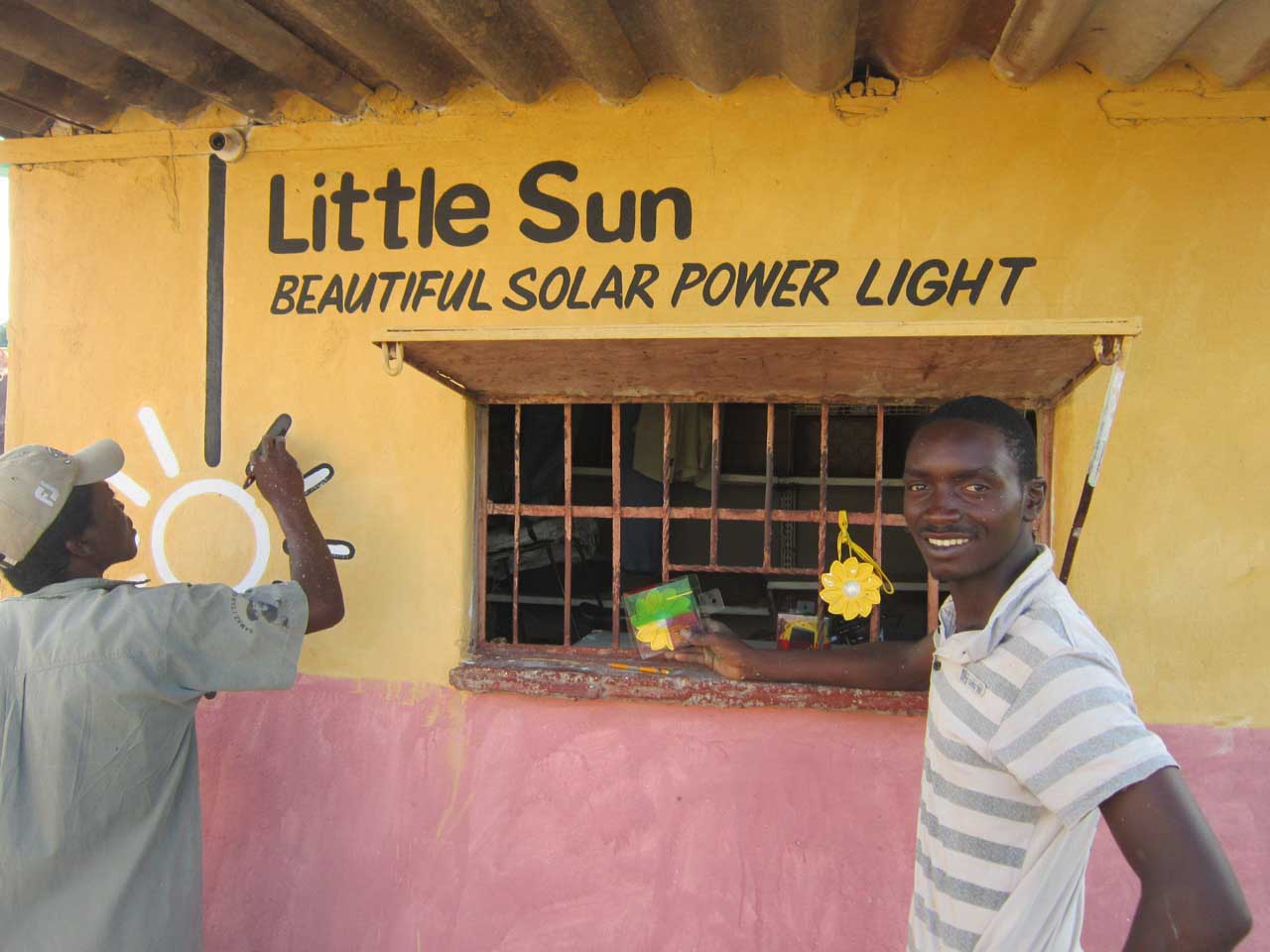

His interest in the physical world has coalesced in a social enterprise project called Little Sun. Conceived with engineer Frederik Ottesen in 2012, the initiative provides portable solar lamps for off-grid areas in sub-Saharan Africa and disaster-stricken regions where electricity isn’t available.

At the end of the presentation, he cited a passage from Lynn Margulis’s book Symbiotic Planet that encapsulates Eliasson’s sensibility as an artist and climate activist.

We need honesty. We need to be freed from our species-specific arrogance. No evidence exists that we are “chosen,” the unique species for which all others were made. Nor are we the most important one because we are so numerous, powerful and dangerous. Our tenacious illusion of special dispensation belies our true status as upright mammalian weeds.

“She went against Darwinism,” he said in conclusion. “Maybe it’s not about competing, maybe it’s about collaborating.”

Those who missed Eliasson’s presentation can see him in action in a particularly engrossing episode of the Netflix series Abstract (“Olafur Eliasson: The Design of Art,” Season 2).