Healthcare would be better if we learned from this old tuberculosis sanatorium in Finland

In a serene forest in Turku, 90 minutes west of Helsinki, is an 87-year-old decommissioned hospital that bears lessons for designing effective healthcare facilities. Commissioned by the Finnish government during the height of the tuberculosis outbreak in the 1930s that claimed thousands of lives throughout the country, the Paimio Sanatorium was conceived as “an instrument for healing.”

In a serene forest in Turku, 90 minutes west of Helsinki, is an 87-year-old decommissioned hospital that bears lessons for designing effective healthcare facilities. Commissioned by the Finnish government during the height of the tuberculosis outbreak in the 1930s that claimed thousands of lives throughout the country, the Paimio Sanatorium was conceived as “an instrument for healing.”

For husband-and-wife designers Alvar and Aino Aalto, the building had a singular goal: help patients recover. This notion seems obvious to hospital architects today, but during a time when there was no medicine for tuberculosis, a well-designed environment was very much the cure. Doctors mostly prescribed bed rest, clean air, a good diet, and sunshine, and architecture was a crucial element in that strategy. In designing the sprawling facility over the course of four years, the Aaltos obsessed over every detail, finish, and fixture to fulfill that brief. They studied building materials, designed furniture, and implemented a color scheme to create an atmosphere that soothed or lifted the patients’ spirits.

“Prior to the development of evidence-based design, Aalto created a healing environment addressing each patient’s psychological and social needs,” explained architect Diana Anderson, in a 2010 article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. “Today it is becoming common for architects to hold focus groups or employ registered health professionals to obtain feedback on the design of health care buildings, but in the 1930s, this was not the case. Aalto was ahead of his time in consulting with physicians as he planned the sanatorium.”

A machine for healing

The functionalist mentality that animates modern architecture is ideal for planning an efficient hospital. Influenced by the writings of Bauhaus pioneer Walter Gropius, the Aaltos turned to the principles of Taylorism, a management theory that sought to optimize flow in workplaces, in planning Paimio.

Because tuberculosis is an infectious disease, the design imperative was hygiene. They created efficient and durable surfaces that were easy to clean and didn’t gather dust. Each patient was assigned their own sink to encourage hand washing and personal hygiene. Though there were lifts—including the Nordic region’s “first scenic elevator”—Paimio’s circuit of canary yellow staircases had low, easy-to-climb steps to encourage exercise.

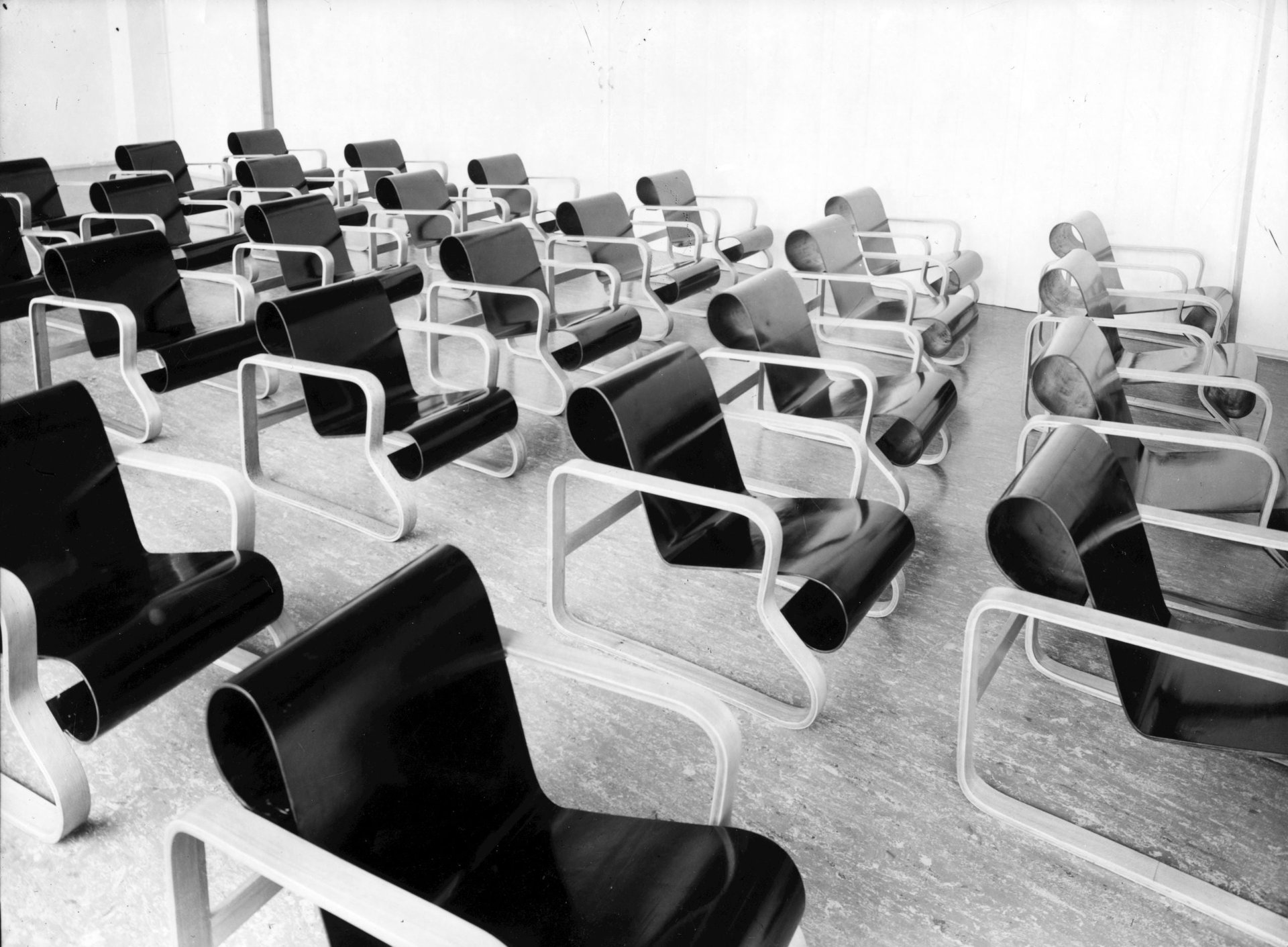

On the top floor is a sundeck overlooking a lush pine forest. Patients were required to sit still and soak in the sun and fresh air in silence as part of their treatment. The Aaltos designed a low-slung bentwood recliner with a back optimized to what was believed to be the best sitting angle for breathing. The Paimio chair, or Armchair 41, as it’s called, is now sold by the Finnish furniture maker Artek and collected by fans of modern Scandinavian design.

Not everything Aalto designed was perfect, of course. Some complained that the tilted faucets in the “noiseless” wash basins tended to splash water all over the floor. Others disliked the skinny lacquered wardrobes in front of their beds because they looked too much like coffins.

Medical use of color

Paimio Sanatorium is worth studying for the fact that it challenges the idea that healthcare facilities need to be white and sterile. Aalto worked with a decorative artist named Eino Kauria on an elaborate multicolor scheme that considered the amount of light that streamed into the building throughout the day. Soothing colors were selected for patient rooms and other rest areas, and sunny yellows and teals injected energy in corridors and dining halls.

“A critical element of the plan was gaining an understanding of the medical role of the original interior colors,” writes Katie Underwood, assistant director of the Getty Foundation, which contributed to Paimio’s conservation efforts. “Every chromatic element was intentional—from red pipes to denote heating elements to calming green ceilings that would dominate the visual field of patients confined to bed rest.”

Walking through the recently restored facility, one can’t help but wonder how the template for public medical facilities has become so bland. Think of all the droll waiting rooms, intimidating diagnostic facilities, or depressing dialysis centers designed with a haphazard, makeshift aesthetic we’ve come to accept as the standard. Paimio, which now serves as a child rehab center, is a vital monument to the idea that the purposeful planning of a hospital—or any type of environment for that matter—impacts our health and longevity in a very direct way.