Despite a landmark discrimination lawsuit, China’s workplace is more stacked against women then ever

A 23-year old woman in Beijing has won what’s believed to be China’s first gender discrimination lawsuit. Earlier this month, Cao Ju, a recent graduate who was refused a job on the basis of her gender, received a settlement of 30,000 yuan (about $4,955) from the company.

A 23-year old woman in Beijing has won what’s believed to be China’s first gender discrimination lawsuit. Earlier this month, Cao Ju, a recent graduate who was refused a job on the basis of her gender, received a settlement of 30,000 yuan (about $4,955) from the company.

It’s a small triumph. Lawsuits related to women’s rights in China are rare. The first successful sexual harassment lawsuit was only in 2009, when an office worker in Guangzhou had video evidence of her boss harassing her. Chinese law forbids employers from discriminating against women in hiring or pay, but gender preferences are so widespread that job adverts often call for only male applicants. In interviews, women face questions about whether they have a boyfriend or plan to get married. Some factories operate by their own guidelines such as not hiring women with children under the age of one.

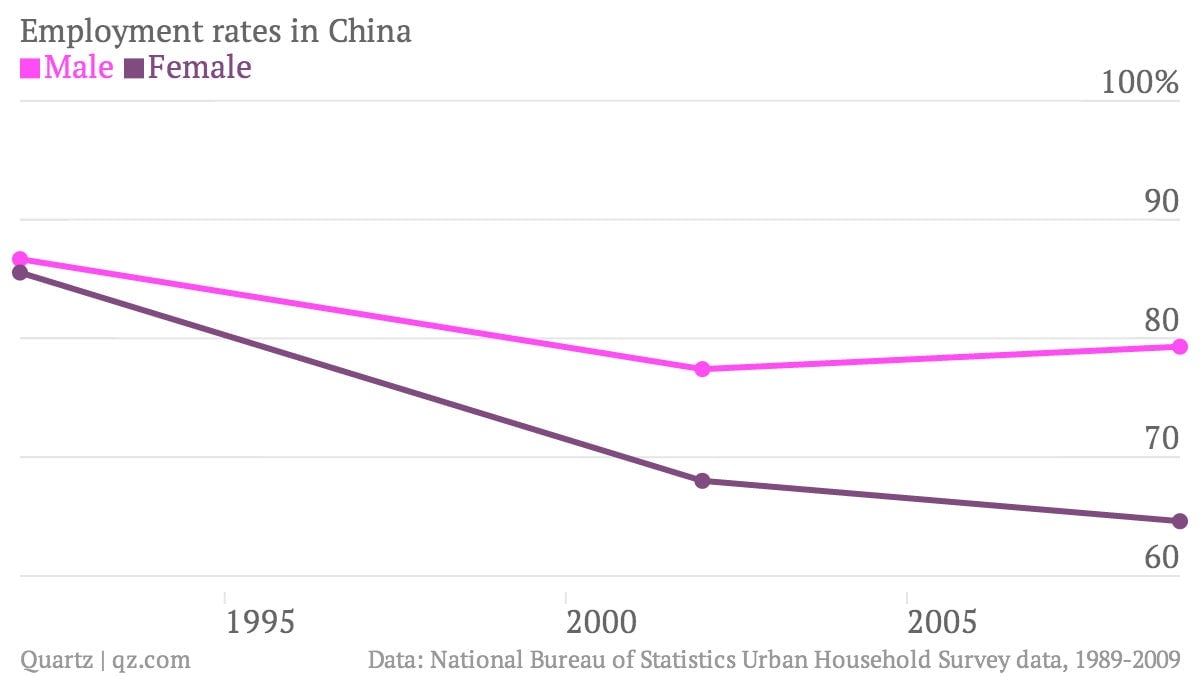

In reality, there’s little to celebrate when it comes to women’s rights in the workplace in China. In the World Economic Forum’s gender gap rankings, China ranks 69 out of 136 (pdf) countries, just below Mexico, Senegal and Tanzania. Despite China’s shrinking workforce, the female employment rate has been falling. In 1992, male and female participation in the Chinese workforce stood at 87% and 86% (pdf, p. 32). While employment for both sexes fell as large-scale reforms of state owned enterprises in the 1990s that laid off millions of workers, male participation improved while women’s only fell lower.

The employment rate is a stark contrast to the days of China’s centrally planned economy when as much as 90% of women were working—part of Mao Zedong’s “women holding up half the sky” philosophy. Now, not only are there fewer women working, but the gap between men and women’s earnings has widened (pdf). Another study on urban employees found that between 1995 and 2007, women’s earnings, as a proportion of men’s, had fallen from 84% to 74%.

The fall in employment and wages can’t just be blamed on the country’s transition from a centrally planned economy into a more market-oriented one. Wei and Bo point out that many other countries that shifted from planned economies—like Poland, Hungary, Russia or Estonia—saw women’s wages improve or stay the same. Wei and Bo attribute the gender pay gap—which especially affects low-end job holders—to the labor surplus China enjoyed for years. As China’s work force shrinks, in large part because of China’s one-child policy, women may have a few more options.