The DEA’s licensing process for narcotics failed as the US opioid crisis worsened

The US Justice Department’s inspector general has found that the agency in charge of preventing drug misuse and diversion failed to stop either as the American opioid epidemic worsened.

The US Justice Department’s inspector general has found that the agency in charge of preventing drug misuse and diversion failed to stop either as the American opioid epidemic worsened.

In a report published yesterday (pdf), inspector general Michael E. Horowitz criticized the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for being “slow to respond” to a sharp rise in opioid use and misuse, for not using the tools at its disposal to better assess and regulate opioid diversion, and for weaknesses in how it handed out registrations to handle controlled substances. “While the Department and DEA have recently taken steps to address the crisis,” the report states, “more work is needed.”

Handling a controlled substances or restricted chemical in the US requires a DEA registration. About 1.8 million have been distributed. The system is meant to “determine the fitness and suitability of the applicant” to sell, prescribe, distribute, import, export, or manufacture narcotics.

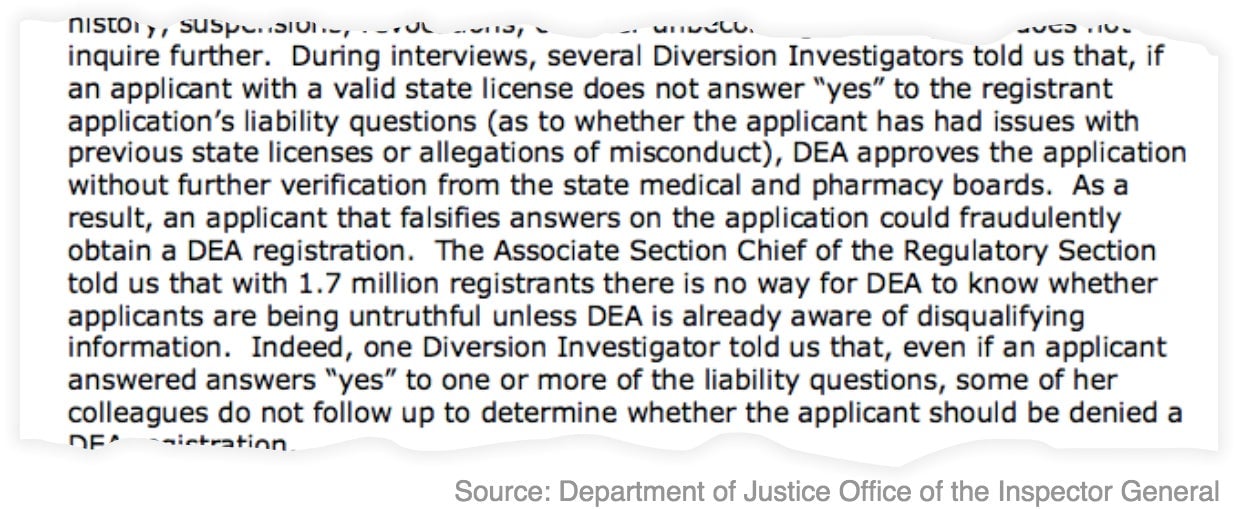

The report from the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found gaping holes in the registration process. The DEA often rubber-stamps approvals for those who already have state licenses, yet is not always aware of doctors or pharmacists who have had state licenses revoked. It relies on the “good faith of applicants to disclose relevant information, even in cases in which the applicant had previously engaged in criminal activity,” the report says.

DEA policy prohibits investigators from performing “criminal background checks” on applicants in favor of less complete “background checks.”

That means they can’t search the FBI’s National Crime Information Center database, nor can they access the DEA’s own internal investigative database, the Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Information System. Instead, background investigations are done using a privately-run commercial database with more limited information. A DEA spokesperson declined to provide details of why the databases are off-limits.

Not enough vetting by DEA

Physicians and pharmacies are not being sufficiently vetted either, the OIG report says. A corporation that owned a pharmacy and was registered with the DEA could sell the pharmacy to another corporation, which wouldn’t have to then re-apply for a registration. And if registrants get their licenses revoked, they can reapply within a day, giving offenders an opening to re-obtain clearance.

Dean Arneson, who leads the school of pharmacy at Concordia University Wisconsin, told Quartz there are other checks in place for pharmacies when the DEA licensing process fails. Individual states usually require “that you need to get approval from the state board of pharmacy,” Arneson said, and pharmacies need to provide proof they have a license.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors are required to report all transactions involving Schedule I and II controlled substances—deemed to have the most potential for abuse—and certain Schedule III and IV substances. The DEA doesn’t require distributors and manufacturers to report orders of benzodiazepines such as klonopin and valium, which are involved in more than 30% of all opioid overdoses. Nor does the DEA track nine opioid compounds, such as cough syrup with codeine.

The agency could conceivably enact a requirement that distributors and manufacturers report all controlled-drugs sales, Holly Strom, former president of the California State Board of Pharmacy, told Quartz. However, this would create its own problems. There are many legitimate reasons for benzodiazepine orders to increase, Strom said—a group medical practice opening nearby with a large number of psychiatrists and primary-care providers, would be one example—and the many legitimate patients taking benzodiazepines but not opioids face a much lower risk of overdose than those taking what can be a potentially deadly combination.

A separate database specifically for reports of suspicious orders was also incomplete and ineffective, says the OIG report. Of roughly 1,400 manufacturers and distributors required to report suspicious orders to the DEA, its suspicious orders database only included reports from eight of them. DEA officials told the OIG that most suspicious orders reports are sent to local field officers and not headquarters, where they would be entered into the centralized system. Yet, when OIG investigators asked to see records verifying this, the DEA was “unable to locate them.”

Reviews of sales are not timely

Finally, the ad hoc system the DEA uses to collect information from the marketplace makes it all but impossible for investigators to keep abreast of current trends, the OIG report says. Some distributors and manufacturers report transactions monthly, others report quarterly. Thus, nothing gets analyzed until the end of the year. The associate section chief of the DEA’s Pharmaceutical Investigations Section told the OIG that the agency would not be able to identify trends and issues emerging in 2018 until sometime in 2019.

“Monthly isn’t appropriate and quarterly is ridiculous, that [data] should be uploaded daily,” Strom said. “If the enforcement entities have their algorithms set up properly, they would see these spikes in orders immediately and they’d be able to respond to them appropriately.”

At the state level, things are different. In California, Strom said pharmacies have to reconcile their inventory of Schedule II drugs every 90 days, matching the prescriptions they’ve filled with all invoices showing what’s been received. Those then have to be reconciled down to the dosage unit, and any overages or shortages have to be reported to the Board of Pharmacy within 30 days. This theoretically allows the pharmacy to stop diversion schemes before they have a chance to get out of control.

Overall, the OIG report paints a critical picture of an agency unable or unwilling to use the tools at its disposal to track the diversion of opioids, identify and crack down on offenders, and perform its primary function—enforcement. From 2002 to 2013, the DEA allowed manufacturers to produce a lot more opioids, including a 400% increase in the production of oxycodone, the key ingredient in the popular painkiller OxyContin. During that same period, the opioid overdose death rate grew by an average of 8% per year, increasing to an astounding 71% per year from 2013 through 2017.

These numbers might seem like a lot but Arneson says sometimes high doses or more prescriptions aren’t an indication of misuse or diversion. “Pain management is…an art. I was always taught that the dose that works is the dose that works.” What pharmacists should do, Arneson explains, is “make sure that the prescriptions are for a legitimate medical purpose and…if they suspect that a person is abusing the medications, that they’re supposed to take steps into reporting that.”

Opioid makers at the center of the landmark National Prescription Opiate Litigation have sought to shift blame onto the DEA’s opioid quotas and regulations, saying they simply followed the rules set out by the agency. It remains to be seen whether the conclusions of the OIG report will play a part in the trial, which is scheduled to begin in October.

“DEA appreciates the OIG’s assessment of the programs involved in the report and the opportunity to discuss improvements made to increase the regulatory and enforcement efforts to control the diversion of opioids,” the agency wrote in response to the report. “While only a minute fraction of the more than 1.8 million manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies and prescribers registered with DEA are involved in unlawful activity, DEA continuously works to identify and root out the bad actors.”

Nick Schwellenbach, director of investigations at the nonprofit Project on Government Oversight, is slightly less generous with his assessment. As he told Quartz, “This report makes clear that, had the DEA’s oversight of these deadly drugs been more robust, thousands of our family members, friends, and neighbors might be alive today.”