Researchers are turning to Reddit drug forums to tackle the opioid crisis

Ryan Le Blanc got his first dose of opioids at three months old, after surgery for a unilateral cleft palate. Now in his late 20s, the English-as-a-second language teacher has gone through about 15 more surgeries of varying severity.

Ryan Le Blanc got his first dose of opioids at three months old, after surgery for a unilateral cleft palate. Now in his late 20s, the English-as-a-second language teacher has gone through about 15 more surgeries of varying severity.

With each operation came new painkillers. At 14, while living in New England, Le Blanc started buying and using illegal opioids for fun. By 16, he was injecting heroin, a habit that he carried from high school through college graduation.

As a teenager, Le Blanc came across Bluelight.org, a drug forum now more than 20 years old. He read post after post—innumerable lines of text and images about the substances he was taking, how to take them safely, and how to quit.

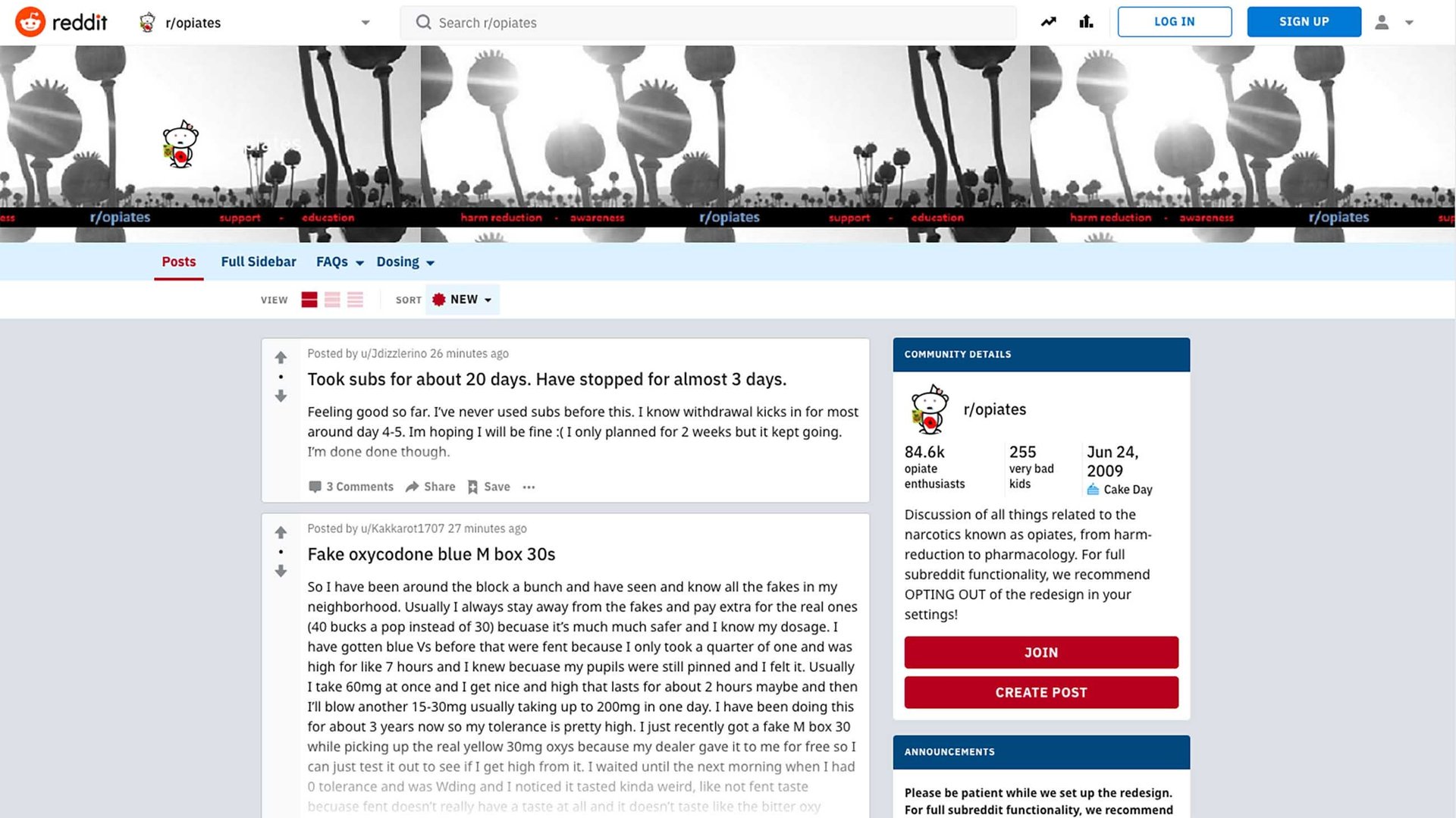

Today, these threads aren’t just of interest to the site’s users. As the opioid epidemic worsens, claiming about 130 lives a day in 2018 in the United States alone, a cadre of researchers is looking for solutions to addiction and overdoses in the sprawl of drug forums. The researchers say that drug forums on the dark net—a catch-all for internet hubs that are often encrypted or unavailable through regular search engines—along with more mainstream counterparts like Bluelight and drug-related threads on the website Reddit, might be a medical or research tool in their own right.

For instance, in research published this past spring, Stevie Chancellor, a postdoctoral fellow in computer science at Northwestern University, used computational linguistics and machine learning—a subset of artificial intelligence—to find how forum-goers on Reddit attempt to get sober. “We wanted to unearth the things the doctors didn’t even know about,” said Chancellor.

Chancellor and other academics, as well as advocates of harm reduction—a philosophy that seeks to minimize the negative aspects of drug use—believe drug forums can provide insight into a secretive subset of society. The forums could also provide a route to reach users with potentially life-saving information about drugs.

Working with these communities isn’t without controversy. Some researchers in this relatively new field have trouble collecting data, particularly when law enforcement busts up an illicit marketplace. But both researchers and folks who use the forums to quit drugs believe there’s value in the chatter.

In Chancellor’s machine-learning study, she and her colleaugues built a computer program to recognize distinct words and phrases in nearly 1.5 million posts on 63 subreddits where people discussed opioid addiction recovery. The program found many Redditors who were trying to quit heroin and fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, were using other drugs to do it.

Chancellor was surprised, but the approach is common on the forums, though sometimes discouraged by moderators and other users: People may use alcohol, cannabis, and heavier drugs to quell withdrawal symptoms. Le Blanc was no exception. At 22, he tried to quit opioids using other drugs, although three years later, after a family intervention, he entered a formal methadone program, which uses a lower grade narcotic to wean users off harder drugs. As of a few months ago, he quit using maintenance drugs, working towards true sobriety to be free of opioids altogether.

Chancellor’s team found other examples of drugs that Redditors leaned on to quit opioids: Benzodiazepines like Valium or Xanax; the anti-diarrheal drug Imodium; ibogaine, a psychoactive plant substance with alleged anti-addiction properties; and kratom, a powdered preparation of a plant that, taken in large enough doses, can cause opioid-like sensations. Others used relatively weak opioids such as codeine to step back from heroin or fentanyl. And the forum-goers also developed elaborate dosing regimens to get through a work day relatively unscathed by withdrawal.

Any benefit from self-administered treatments would need to be verified or tweaked by medical professionals, Chancellor said. Mixing some of these drugs can be deadly. Even Imodium, when taken at recreational doses—more than 15 times the therapeutic dose—can cause severe heart problems.

The fact that people are using such an array of drugs to quit opioids is a clinical and medical blindspot, Chancellor said: “I think there’s a lot of potential for communities to back-inform what could be productive investigations for medical researchers.”

Online forums may provide other useful data and anecdotes for researchers. For Monica Barratt—a psychologist and sociologist at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, as well as Bluelight’s director of research—they could hold the answer to a complex question. How has the rise of dark net markets impacted public health?

Barratt studies the intersection between drugs and the internet. Through interviews and surveys with these secretive communities, as well as forensic data from local police, she hopes, in part, to discover if the availability of mail-order illicit substances encourages more people to use drugs, or if they would be using them anyway. So far it seems to be the latter, Barratt said.

Indeed, the forums can also be a relatively judgement-free place for users to turn to when looking to quit drugs. For some, choosing a DIY detox—including those studied by Chancellor—is a matter of preference. But for others, it’s a matter of necessity. In rural areas—including New England, where Le Blanc experienced detoxing first-hand—the few addiction clinics are spread thinly across the region. Patients may travel hours each day for medication.

With no real option for in-person treatment, internet-savvy drug users who want to detox have few choices: They can detox blindly, or turn to their peers’ collective knowledge online. Barrat argues that the latter can provide “a safe place for people to talk about what’s going on and to ask questions.” The semi-anonymous nature of the markets may also cut down on some of the violence that comes with street-level dealing, like robbery, theft, and assault, other research has suggested.

Despite the upsides for some people who want to quit opioids, the dark net still poses problems both for law enforcement and users. Alongside the forums for detoxing are others dedicated to taking drugs, as well as marketplaces that sell drugs like heroin tainted with fentanyl.

While the drugs are online, the dark net is not a big contributor compared to the broader global illegal drug trade, said Neil Walsh, chief of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) cybercrime and anti-money laundering units. Online sales are similar in amount and cost to a street level dealer—priced to sell in small doses, not in bulk.

Still, Walsh added, the everyday internet and the dark net can connect large scale dealers with the laboratories that produce drugs like fentanyl, or the chemicals needed to make them. The online marketplaces also offer chemicals that aren’t typically found on a street corner. These “designer drugs” or “research chemicals” are intentionally obscure and—until laws change to ban them—chemically different enough from better-known drugs to be technically legal.

Despite the dark net’s relatively small piece of the drug trade, law enforcement agencies around the world are trying to shut down its markets. By some accounts, the approach is working. According to Walsh, after Operation Bayonet in 2017—an international law enforcement effort which closed two large markets called AlphaBay and Hansa Market—there was a noticeable decline in customers buying drugs from the dark net. And according to the 2019 UNODC’s World Drug Report, 15% of customers reported using the dark net less frequently after the closures, and 9% said they stopped buying from the markets entirely.

But many people just move to new markets. With the collapse of the major players in drug-selling crypto-markets, Walsh added, buyers dispersed to many of the smaller markets scattered across the dark net. And there is also an uptick in some regions, according to the 2019 Global Drug Survey, which reported that the English-speaking world has seen a steady increase in people who have reported using drugs purchased over the dark net for the past six years.

The closure of dark net drug markets has also had an unforeseen downside, at least in research: The increasingly lack of anonymity has led to an erosion of trust. For some researchers, this can make tracking down willing participants difficult. And for some harm reduction advocates, the looming threat of police crackdowns can be cause for worry.

Angus Bancroft, a sociologist at the University of Edinburgh, is still in the early stages of his research, but it’s already difficult to track down customers willing to talk.

Much like Chancellor, Bancroft hopes to use machine learning to study drug use and recovery in online communities, though mostly he’s looking at the dark net, rather than the forums out in the open.

His team has begun early work on a computer program and preliminary talks with the operators of a few dark net forums. But police are simultaneously trying to close down the forums, which has made the people who post there wary.

“With the dark net, I think you need a longer engagement to build up trust,” Bancroft said.

If Bancroft can get enough participants, his team plans to create a computer program that can recognize shifts in drug habits and the emergence of new chemicals on dark net markets. Bancroft hopes to use the findings to pull in relevant harm reduction information, and use both dark net forums and sites like Bluelight as a way to spread it to the users.

Bancroft’s work may be something relatively new to academia, but it’s following in the footsteps of other harm reduction advocates such as Fernando Caudevilla, a family physician based in Madrid, Spain.

Caudevilla may also serve as a cautionary tale. Between April and October in 2013, he posted on Silk Road’s drug forums as DoctorX, answering 321 public questions about drug use and safety before the FBI closed it down. Silk Road’s operator, Ross Ulbricht was later arrested.

The next month, the remaining Silk Road staff started Silk Road 2.0. There, Caudevilla answered 352 public questions before the market, too, was closed down in 2014 by a joint FBI-Europol operation called Operation Onymous. After Caudevilla spoke in defense of Ulbricht in his trial in 2015, backlash from the American media and government caused him to log off from the dark net, he said.

But that hasn’t stopped Caudevilla from continuing his work on the regular web. He has shifted his responses from around 250 of the most pertinent questions he had answered on the dark net forums, and moved them to the website for Energy Control, a Spanish harm-reduction organization. The organization also regularly checks samples of drugs purchased off the dark net, which users send in to check for harmful chemicals like fentanyl.

In one case in 2018, Energy Control found the source of the fentanyl, and the marketplace banned the seller and the sale of fentanyl and similar drugs. Not everyone on the dark net is evil, Caudevilla said. Some are honest and willing to collaborate with harm reduction efforts.

“It’s not perfect,” he said. “But I think it can achieve good things.”

Le Blanc, now a moderator on Bluelight, agrees. As a veteran of the cross-section of drugs and the internet, he said he truly believes there is life-saving information on the forums.

“We’re the ones who say ‘Okay, we’re gonna tell you how to do this even though it’s really not a smart thing to be doing. Here is the most reasonable way of approaching this situation that you are in,’” Le Blanc said. “That’s harm reduction in a nutshell.”

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.