The 20-year old book that makes everyone want to quit their jobs

Let’s admit it: Money is emotional. With more money comes the freedom to live on your own terms and invest in the people you love the most. Money, some may say, gives you life.

To Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez, money didn’t increase their serenity nor their personal freedom—money (or at least the process of earning it) meant taking it away.

The two wanted to “transform the way Americans think about, earn, spend, and save their money,” according to Robin. They were frustrated by people who complained about their jobs but who kept doing them in order to accumulate more stuff they didn’t need. That way of life was fundamentally at odds with most people’s stated values, yet they continued to live that way.

In 1992, the pair published a book called Your Money or Your Life: 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship with Money and Achieving Financial Independence. Today, it has sold over 1 million copies and garnered a cult following, particularly among devotees of the Financial Independence and Retiring Early (FIRE) movement.

Nearly 30 years after its initial publication, the book is still radical. It’s no longer completely novel to suggest that less stuff can mean more life—the global financial crisis sparked outrage about the continued excesses of large corporations, leading to the rise of minimalist gurus like Marie Kondo. But the book’s provocative exercises challenge the reader to better align their actions—specifically the way they earn and spend money—to the things that are actually important to them.

Your Money or your Life is a philosophy masquerading as personal finance, with a message that is more resonant now than ever before.

What do you have to show for it?

Robin is adamant that transforming our relationship with money requires us to account for the movement of every single penny in our lives. This should be relatively easy in the era of Venmo and online banking. Yet according to the financial institution US Bancorp, only 41% of Americans maintain a budget. And by turning a blind eye to our spending, Robin is convinced that we’re falling into a dangerous trap.

The book’s fourth edition was released in 2018 and spans 366 pages over nine chapters. Each chapter contains one of the nine steps (like Chapter 3: How much is enough?) and is a mix of historical background, case studies, and exercises to help readers implement the steps.

Dominguez was a former Wall Street analyst who had retired in 1969 at 31. Robin was an aspiring actress who had become self-sufficient off of a modest inheritance ($20,000 in 1969). After meeting on a road trip in the 1970s, they started producing workshops together teaching Dominguez’s method. The book soon followed.

Robin and Dominguez, who were, in Robin’s words, “work and life” partners (Dominguez died from cancer in 1998), had aimed their book at a very specific audience: people who hate their jobs but do them to make money. They argued that these people were blind to the time and energy they were spending in the pursuit of status and materialism. They wanted their readers to re-assess if the things they felt they needed to “rise through the ranks” (cars, private schools, clothes and “the right house in the right neighborhood”) were worth the sacrifice required to get them.

In one of the book’s early exercises, Robin prescribes a form of exposure therapy to reacquaint the reader with all their past money decisions. This exercise is both laborious and laughable: The reader is instructed to add up all of the money they’ve ever earned in their lifetime and compare it against their current net worth.

This exercise is intended to wipe the slate clean. It clears what the book calls “the fog shrouding your past relationship with money” and makes you let go of “any secrets or lies that may be distorting your current relationship with money.”

So I committed 15 minutes to trying it.

While my net worth is quite easy to calculate (I’m a debt-free renter who mostly owns index funds), calculating my lifetime earnings (ranging from a camp counselor in 1995 to my last Wall Street bonus in 2015) felt impossible. Regardless, I created a Google Sheet that had 26 rows (one for each year since I started making money) and dropped in a ballpark amount, guessing wildly for those early years. I actually got a bit nervous as I typed in the “sum” formula and waited for the verdict. Let’s just say that the first number (earnings) was much greater than the second one (net worth). Quickly my mind re-litigated a long list of wasteful purchases.

The exercises peppered throughout the book, too difficult for most people to actually complete, are designed to shift the reader’s mindset away from over-consumption and shine a light on whether their spending is in accordance with their values.

Life energy: your most precious resource

The old adage “time is money” underpins most service-based economies, and therefore many jobs in the United States. But like the prior exercise, Robin and Dominguez want the reader to feel this trade off viscerally. In their method, every purchase needs to be converted into “life energy,” which is your hourly wage adjusted for the costs you incur to do your job (i.e. dry cleaning, tolls, that cold you caught from a coworker). Yes, that means looking at your Starbucks coffee, new iPad, and wedding videographer to quantify if you are willing to trade that many hours of your life for each purchase. (What about services like childcare and dog walkers that enable you to buy back time? Robin and Dominguez would approve, as long as you could demonstrate they were aligned with your values.)

But here’s an extra wrinkle: People are really bad at putting an actual value on their time. Ashley Whillans, an associate professor at Harvard Business School, demonstrated this inconsistent behavior in the article “Time for Happiness: Why the pursuit of money isn’t bringing you joy.” She cites studies showing that 818 Danish millionaires “said that they didn’t spend anything to delegate disliked tasks to others;” of 300 adults in romantic relationships, “only three said they would [spend $40] to save their partner’s time.” She also analyzed 42,721 employee responses from a Glassdoor survey and concluded that “non-cash benefits such as social experiences and the opportunity to take leaves had a greater impact on job satisfaction than money did.”

It turns out we’re pretty bad at aligning our spending with our values.

In fact, we’re even worse at figuring out what kind of spending actually makes us happy. A big part of the reason, according to Robin and Dominguez, is because of marketing and media. They write: “’Whoever dies with the most toys wins’” is part of the design to keep us all in the system and playing… it’s all part of the game, we tell ourselves, the only game in town. The game feeds on players being involved. If players lose interest, the game collapses—which horrifies us.”

We’ve internalized these narratives, told ourselves this is what we want instead of seeking out things that actually make us happy. Many of us have never even thought critically about what those happiness-inducing things might be. Robin and Dominguez argue that breaking the cycle requires you to intimately understand the impact that every dollar has on your mood (or “life energy,” as they call it), your happiness, and your larger aspirations—which is why every exercise in the book requires you to run a fine-toothed comb through all every financial decision you’ve ever made.

What you have is enough

As I navigated the book’s exercises, I found more clarity and less anxiety in my own history and thoughts about money. The clarity arose from a newfound awareness about my spending—did it come from a place of fear or desire? Instead of always buying the most expensive health insurance plan, I realized that overspending on healthcare premiums was driven by a deeper fear: my own (uninsurable) mortality. Paying the highest premium definitely wouldn’t make that go away. I stopped indulgent impulse purchases such as fancy running gear. And in a very Kondo-ian way, as I stopped buying unnecessary stuff (for me, mostly gadgets), I realized that not needing to recharge, store, and maintain stuff gave me more peace of mind—and, yes, increased savings.

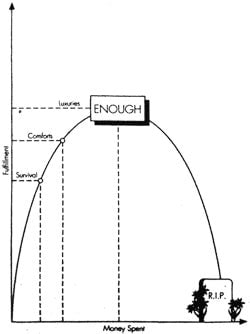

One of Robin’s paths towards this improved you draws from a core tenet of Eastern philosophy, which ties happiness (or transcendence, or Nirvana) to the absence of desire. She believes that people generally misunderstand the relationship between fulfillment and how much money we spend. Most people use the dollars they earn to first cover basic needs (food and shelter), then their comforts (Netflix account and gym membership), then luxuries (a nice apartment and a luxury SUV). The further along you get in this process, the logic follows, the more fulfilled you are, and that’s supposed to continue as you make more and more money.

However, numerous studies have shown that this effect peters out. At some point our fulfillment begins to decrease even as we’re spending more. Consider this chart from Robin and Dominguez’s book that sums up their thinking on the issue:

The book’s authors note that this misunderstanding about money and fulfillment “enters our lives through the flawed belief that more is better” and that “inner fulfillment [lies] in outer possessions.” The book’s exercises are intended to break readers out of that belief and guide them to the place of enough.

And finding that enough point is powerful, its authors write: “[It’s] a fearless place. A trusting place. An honest and self-observant place. It’s appreciating and fully enjoying what money brings into your life and yet never purchasing anything that isn’t needed or wanted.”

Robin has been financially independent for nearly the past 50 years—it’s not hard to see why FIRE devotees idolized her. But in January 2019, she announced on her blog that FIRE was not actually “her tribe.” She seemed mildly disillusioned that most of the people in the movement were obsessing over the “getting out part” and the minutiae “about taxes and investments.” They were missing the point.

To Robin, financial independence was “never the ultimate goal.” Her mission, and that of her work, had always been about the “freedom to pursue a higher purpose—to grow spiritually, to learn, to create and to serve.” Robin’s renewed call-to-action is less clear that it might have been before but touches on today’s pressing issues: politics, policy-making, reducing inequality, universal basic income, national service, and the environment. She implores those who were obsessive about implementing Your Money or Your Life to use “their smarts and capacity for focus and skill… to make a big difference in small and big ways.”

Robin reminds us that a transformed relationship with money isn’t just about how you feel. Yes, some will read her book and become financially independent. But this independence doesn’t absolve you from your responsibility to your communities—and the Earth more broadly.