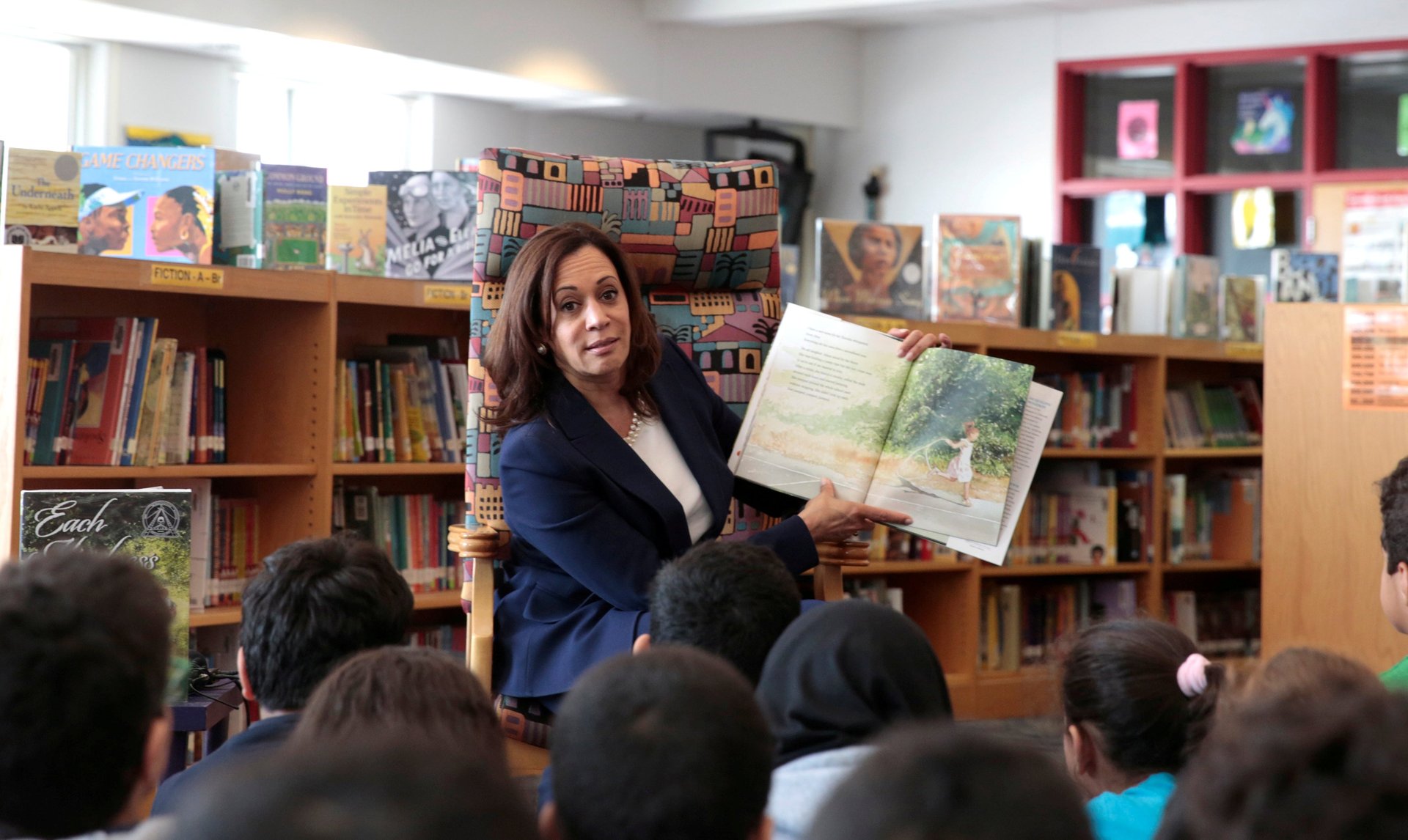

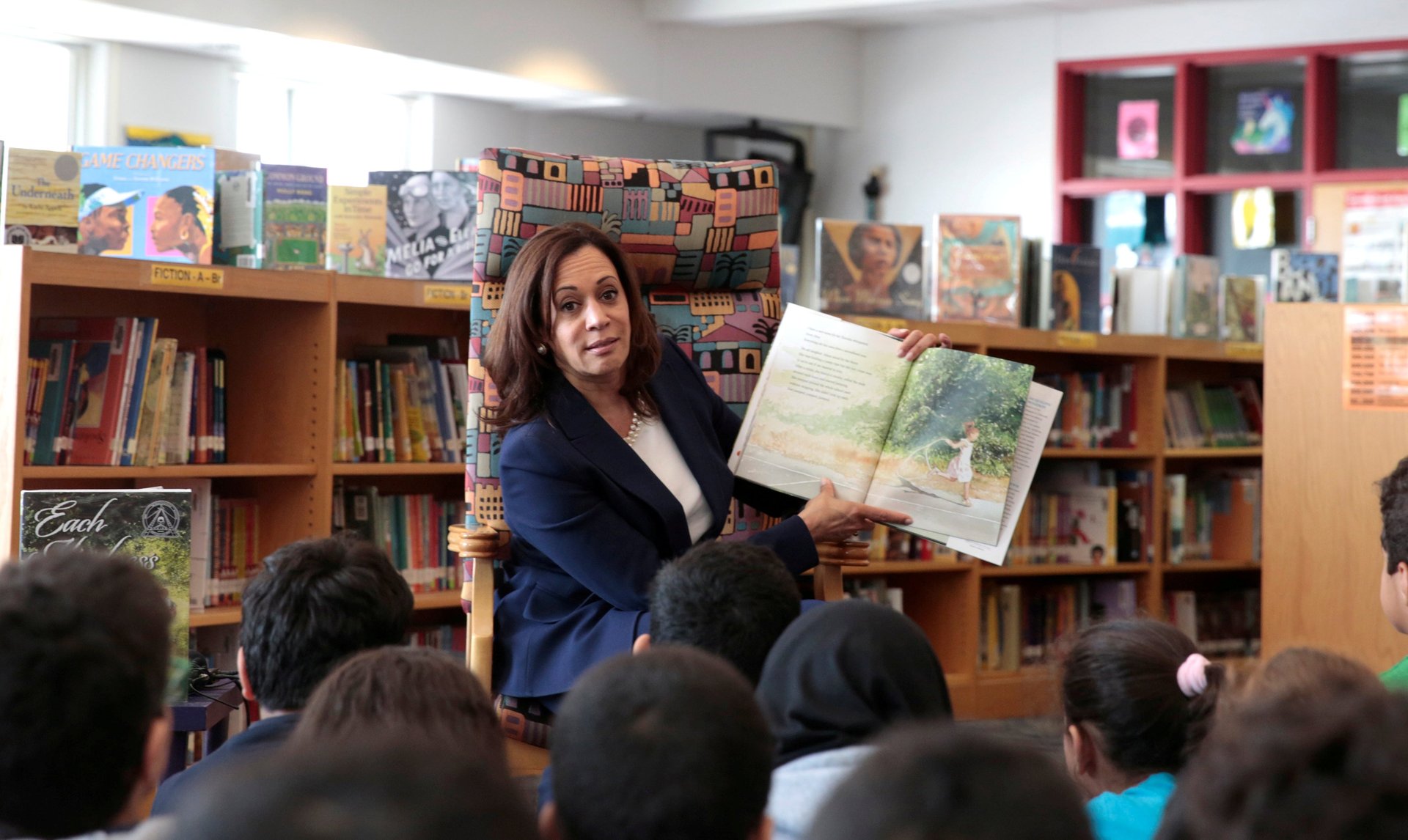

How Kamala Harris’ extended school day bill could affect teachers and kids

Today, Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) introduced a bill that would extend the US public school day to 6 pm. Harris, along with her five Democratic co-sponsors, believe the bill would help ease the burden on parents, who struggle to find childcare between 3 pm and 6 pm. In those hours, which typically fall between the ends of the school day and parents’ work hours, parents have to scramble for a babysitter, for transportation to and from after-school programs, or are forced to leave work themselves. And this burden falls most heavily on women, as The Atlantic points out.

Today, Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) introduced a bill that would extend the US public school day to 6 pm. Harris, along with her five Democratic co-sponsors, believe the bill would help ease the burden on parents, who struggle to find childcare between 3 pm and 6 pm. In those hours, which typically fall between the ends of the school day and parents’ work hours, parents have to scramble for a babysitter, for transportation to and from after-school programs, or are forced to leave work themselves. And this burden falls most heavily on women, as The Atlantic points out.

So the bill, if passed, would likely benefit many parents, easing both the logistical and financial burdens of after-school care. But how about teachers, who need time in the afternoons to plan and grade, and students, who are accustomed to having those hours to do extracurriculars—or simply something other than sitting still and being quiet? The experts that Quartz spoke with agreed that Harris’ plan is good in theory, but whether it would actually work depends on the specifics of the rollout.

Harris’ plan wouldn’t affect the number of hours individual teachers work—that’s strictly limited by their contracts. Indeed, the bill stipulates that teachers and other school staff won’t have to work extra hours unless they want to, in which case they would be compensated at the same rate as their regular day.

Lots of schools already do this—it just hasn’t been required. “The way schools usually do it, it’s not the same adults in the building all the time. Other people come in and handle the extended part of the day,” says Tim Daly, the co-founder of EdNavigator, a nonprofit focused on balancing education and the needs of families.

And students wouldn’t necessarily be trapped in classrooms for that extra time. “My guess is that schools wouldn’t use this for instructional time,” Daly says. “They could decide that the instructional day ends at 3:15 pm, but the time until 6 pm could be devoted to non-academic endeavors, something more akin to an after-school program.” Schools could also make this post-instructional time optional for families with kids who already participate in other enrichment programs.

The bill addresses the issue of after-school programming, calling for schools “to leverage community resources, such as nonprofit or government programs for children or interested stakeholders in the community, to provide academic, athletic, or enrichment activities during the additional school hours.”

So Harris’ proposal wouldn’t necessarily change much for students or for individual teachers. But for school districts, what this idea does amount to is a lot more money. Though the bill calls for five-year grants of up to $5 million, as well as $1.3 billion for summer programming, that’s not the same as a long-term plan to keep schools funded for those extra hours. “We all know how legislative funding disappears. [If that happens,] then those kids are left high and dry,” says Maria Ferguson, the executive director for the Center on Education Policy at George Washington University.

“[Harris] is not the first person to talk about this, that’s for sure,” Ferguson says. “Logistically, it’s really complicated to pull off. You have to have teachers there, you have to train them, and you need additive value to the programming.” And schools will need to spend more money to ensure those programs are properly vetted and safe, she adds.

One theme underlying this conversation is inequality. Wealthier parents are likely already paying for their kids to be enrolled in enriching after-school programs, so a longer school day might help give kids from poorer families more access to those kinds of programs—if they’re executed properly. “What you do from 3 pm to 6 pm matters. Just engaging in more of same old drill-and-kill, or putting [students] in the presence of adults who don’t care, you won’t be doing much good,” Ferguson says. “It may not hurt—they’re in a safe place—but it won’t add anything. It all depends on the doing of it.”

Harris’ bill (or one like it) might even give low-income parents more economic opportunities. “Policies like this one can help families, and will likely benefit women the most, since they are often the default caregiver (or person who finds the childcare solution),” says Sarah Cohodes, a professor of economics and education at Teachers College at Columbia University. “The evidence on preschool and kindergarten expansion shows that women often increase their labor force participation when their child participates, and a policy like this one would likely also support parents’ ability to work.”

The five-year pilot period mentioned in the bill might help policy-makers determine whether it’s having the intended effect.

But some experts note that this plan won’t solve all the problems in education. Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, one of the largest teachers’ unions in the US, has publicly supported the bill. But in a statement to Quartz, she emphasized the need to focus on how students are spending their time in school, not how much time they’re spending: “The solution to the challenges facing our students and educators in America’s public schools isn’t instructional time or fewer days per week. While we already spend an hour more per day teaching kids than the countries who out-compete us, we need to be thinking of how to make it meaningful, not have fewer days with kids in school,” Weingarten said in a statement, suggesting tactics like limiting class sizes and using the community school model.

“Anytime you’re offering students an opportunity to engage in high-quality learning, that’s a good thing. But the devil is in the details,” Ferguson says.

Correction: This piece previously misspelled Tim Daly’s name.