It’s not just Obamacare. In the future, we’ll all work less

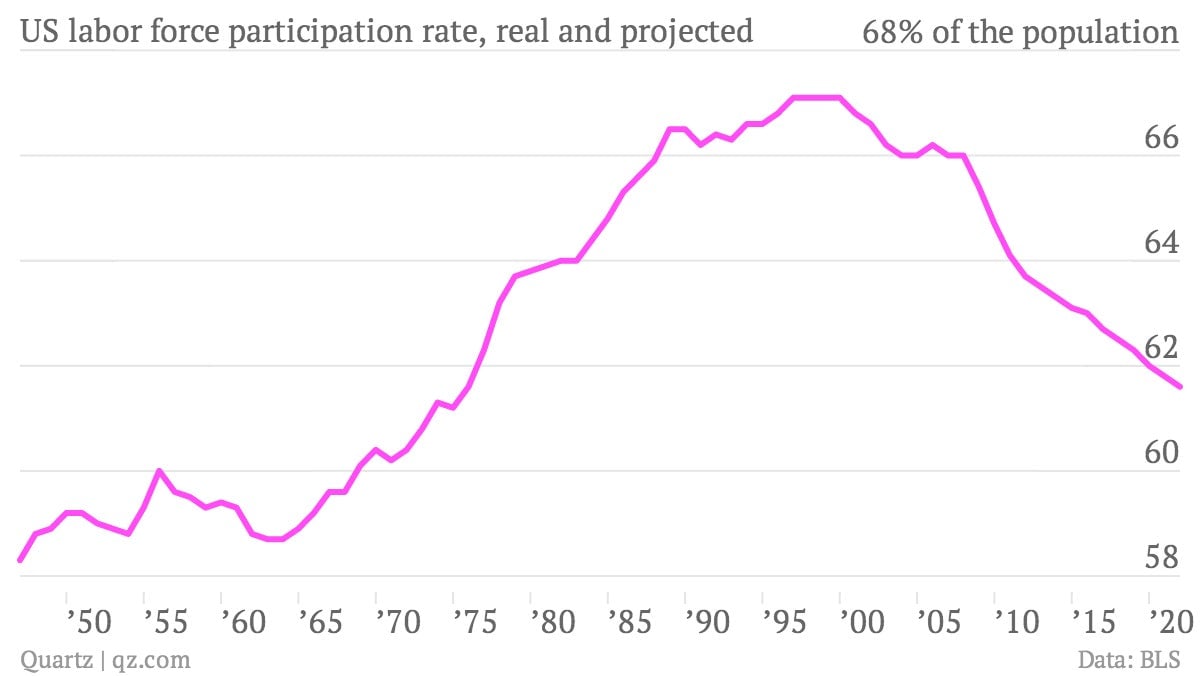

A new forecast that America’s new health care law could lead some 2 million workers to leave the workforce has become a political flashpoint in the US. But short-term infighting over the US welfare state is missing the point—all the trends in the modern economy are leading toward less work, and Obamacare’s effects are something of a drop in the bucket:

A new forecast that America’s new health care law could lead some 2 million workers to leave the workforce has become a political flashpoint in the US. But short-term infighting over the US welfare state is missing the point—all the trends in the modern economy are leading toward less work, and Obamacare’s effects are something of a drop in the bucket:

Because Obamacare works to delink health care from employment by improving and subsidizing the insurance market for individuals, fewer Americans will need to work full-time simply to obtain healthcare, or delay their retirement until age 65 to access Medicare, the public healthcare program for seniors. Instead, they can work part-time and retire sooner, and, because of the way subsidies reduce with income increases, some low-income workers will have less incentive to seek small increases in hours or wages—although this also means that their employers will have an incentive to pay them more.

This will reduce some combination of hours worked and the size of the labor force itself, and it has spurred a debate over whether this phemonenon is good or bad. Most people make a distinction between voluntarily leaving the labor force for other pursuits—work ain’t everything, ya know—and not being able to get a job when you need one. But there are worries about the non-pay benefits from working or who, exactly, will be paying the taxes needed to subsidize all this.

But that’s not a discussion about Obamacare. It’s a discussion about the future of wealthy economies. First, there’s the aging population: Absent increased immigration, the population is going to get older and the workforce will shrink. There are also economic trends: More work is done in the service and knowledge sectors of the economy, and productivity gains mean fewer people are needed to grow food and make goods. There will also be more pressure for workers to increase their education level, keeping younger people out of the workforce longer.

This is the post-industrial economy of the future that inspires both trepidation and hope: The hollowing out of traditional middle-class jobs and the fact that increasing returns from technology benefit capital more than labor stoke fears of rising inequality. But the hope is that this trend could be an opportunity to reform economic institutions and improve human flourishing, and not just for the poor and the shrinking middle class—even the best-paid workers are wasting their best years working too much, even when all those long hours don’t necessarily produce anything at all.

So think of Obamacare as a tentative first step in what will be a multi-decade debate over what to make of a society in which the returns on labor are shrinking. There’s good reason for some controversy over health care, but we haven’t seen anything yet.