The US government holds balloons to stricter standards than it does voting machines

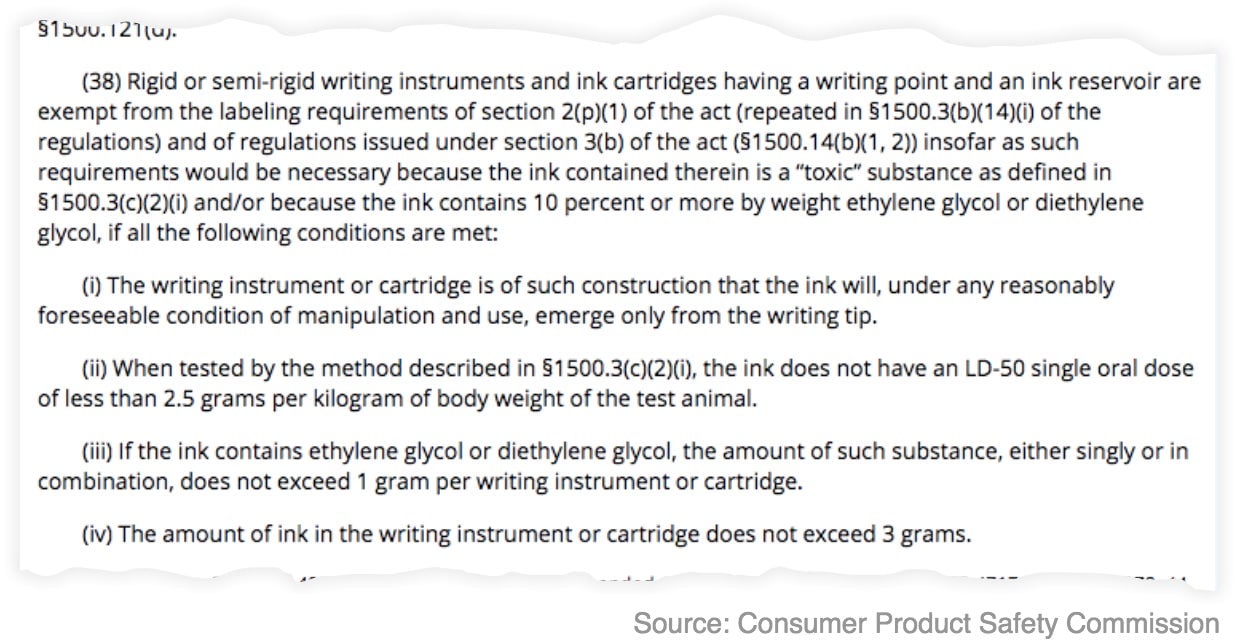

The US government regulates everyday consumer products more tightly than it does the nation’s voting systems, which means things such as balloons, colored pencils, and hair dryers—and the companies that make them—are subject to stricter federal oversight than America’s election infrastructure.

The US government regulates everyday consumer products more tightly than it does the nation’s voting systems, which means things such as balloons, colored pencils, and hair dryers—and the companies that make them—are subject to stricter federal oversight than America’s election infrastructure.

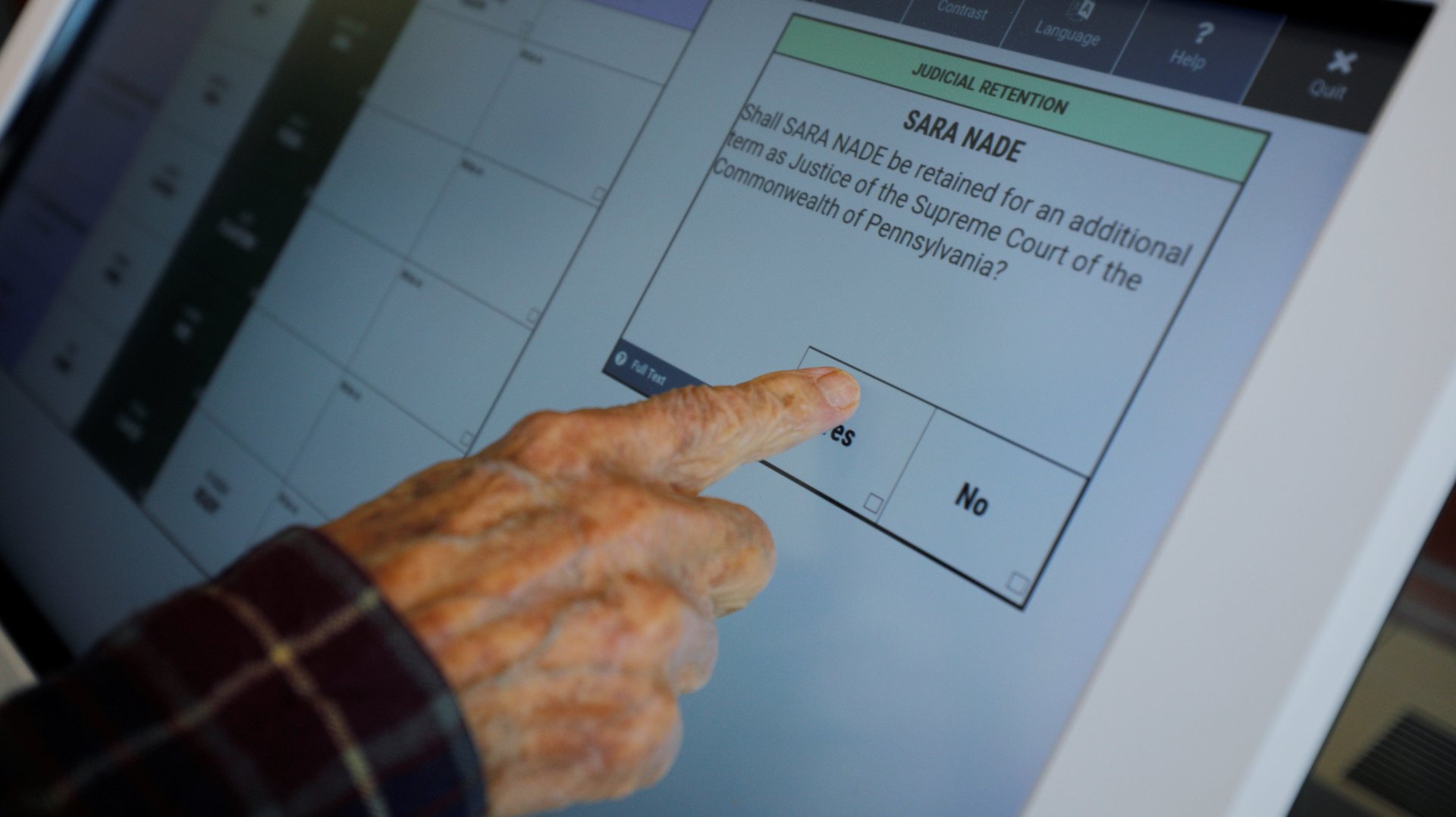

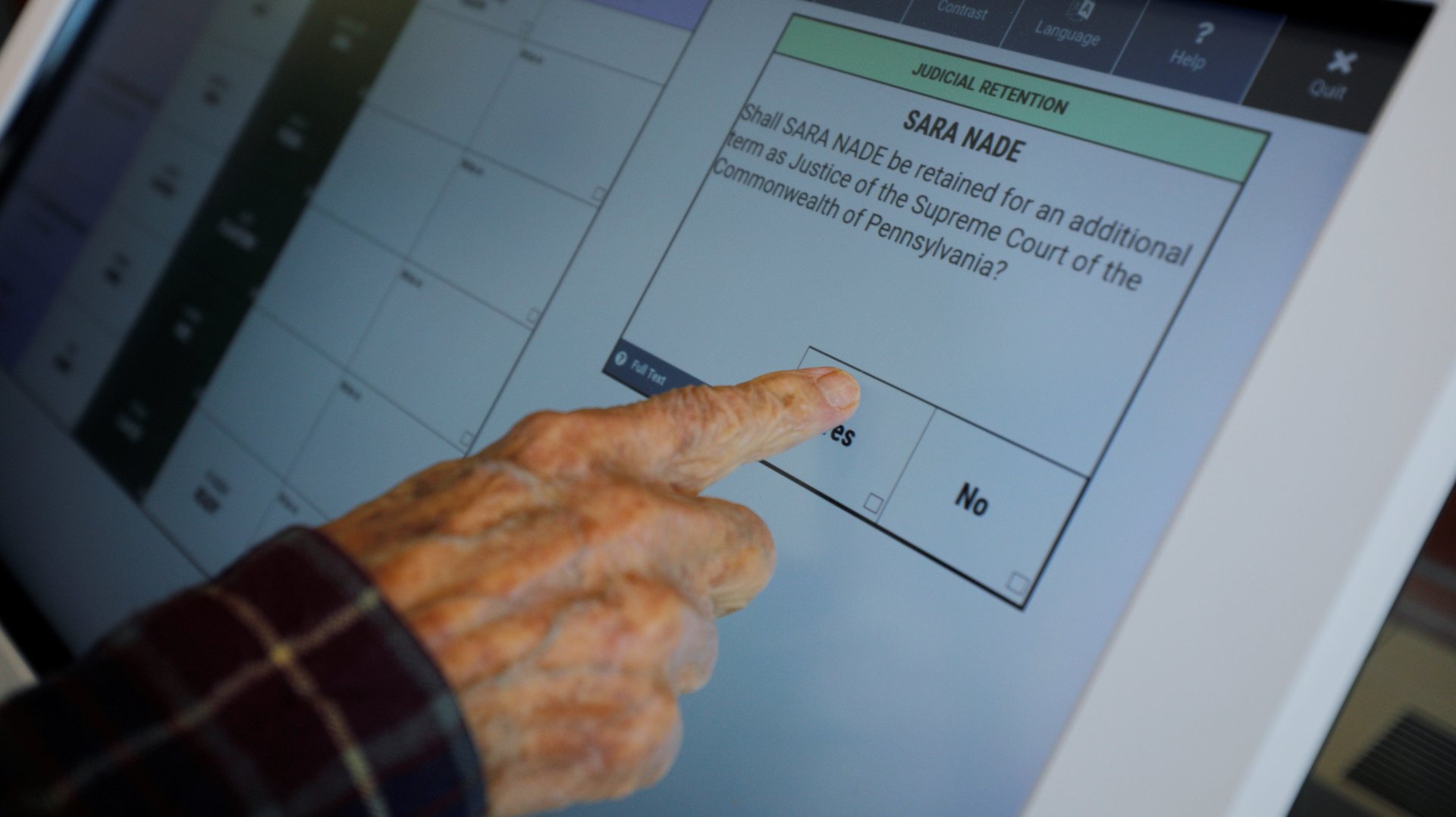

The 2016 attacks on the US presidential election, along with warnings by the intelligence community that further foreign interference is expected, make securing America’s elections crucial. Yet, aside from being held to “some functional requirements under a voluntary federal testing and certification regime,” voting machines and their manufacturers are “largely free” from US government supervision, according to a new report from the Brennan Center for Justice.

Right now, oversight of election systems is primarily the purview of state and local authorities. Manufacturers of voting machines are not mandated to report system irregularities or foreign ownership or control, nor are they obligated to patch faulty software or secure sensitive physical infrastructure, the report says. Further, vendors of voting systems are not required to perform background checks on employees, which the Brennan Center flags as a serious issue. System testing only occurs at the end of the manufacturing process, and doesn’t ensure that vendors adhere to proper supply chain or cybersecurity controls during the development, programming, or deployment phases.

Although the Senate recently approved a $250 million spending bill to protect the 2020 elections from outside interference, experts say this amount “doesn’t come close” to what’s needed. Proper funding could support, among other things, a robust federal regime with formal standards for all vendors, meaning US election infrastructure would have to conform to the same sorts of standards as baby rattles, charcoal briquettes, antiquing kits, pajamas, ballpoint pens, bunk beds, carpets, stuffed animals, garage door openers, plant food, toy trains and, of course, balloons.

Elections in the Unite States are overseen by the Election Assistance Commission, a federal agency that helps states and counties run elections and certifies the machines used for voting. Three companies, Election Systems & Software (ES&S), Dominion, and Hart InterCivic, dominate the relatively small “voting technology” industry, which generates total revenues of about $300 million a year. All three firms’ systems have reportedly had issues with accuracy and faced accusations of miscounts.

The three firms focus mostly on sales, with little effort in the area of new product development, according to ProPublica. They are quick to file lawsuits against counties over contractual and equipment issues, J. Alex Halderman, a computer science professor who studies election equipment, told the publication.

“The vendors have made election officials fearful of working with researchers to independently test equipment,” Halderman said.

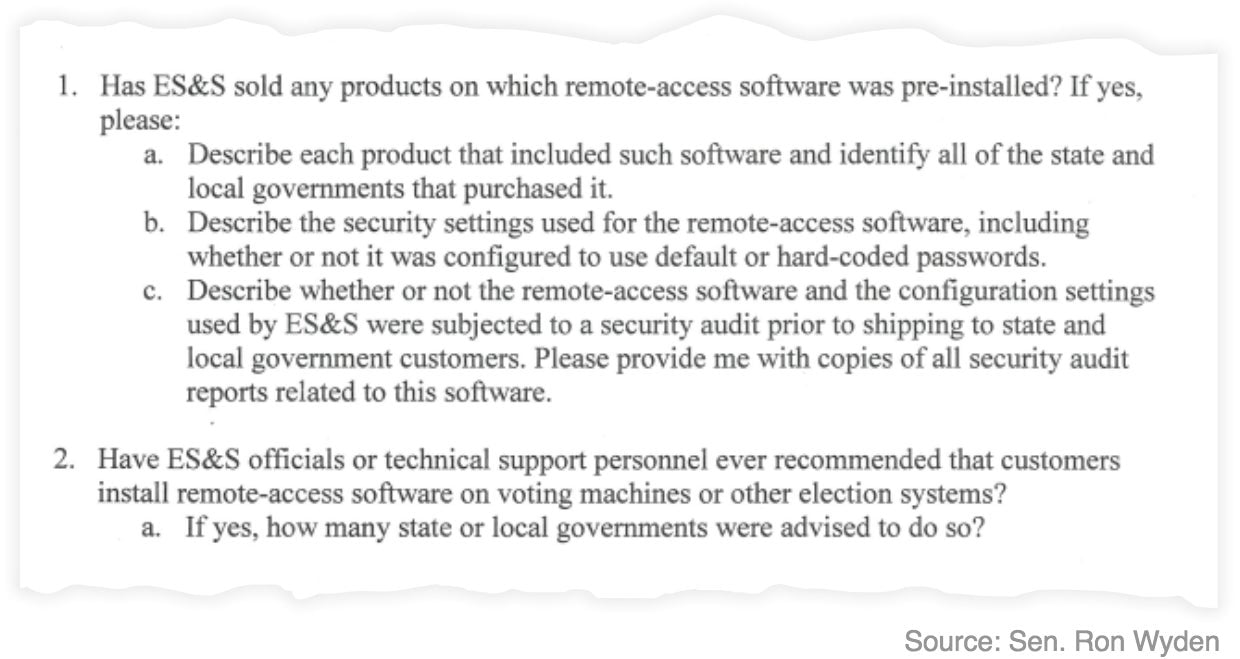

In 2018, senator Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, sent letters to each of the major voting systems manufacturers asking for details about the security of their machines. None provided a sufficient response, Wyden said.

“The maintenance of our constitutional rights should not depend on the sketchy ethics of these well-connected corporations that stonewall Congress, lie to public officials, and have repeatedly gouged taxpayers, in my view, selling all of this stuff,” Wyden told attendees at an election security conference earlier this year.

In a statement provided to ProPublica, ES&S said Wyden “is entitled to his opinion,” arguing that the “evidence shows the market functions properly.”

To the contrary, Wyden said, “The market is broken. Markets work well when you have tough standards, when you have real regulations and vigorous oversight. And here you have none of that.”