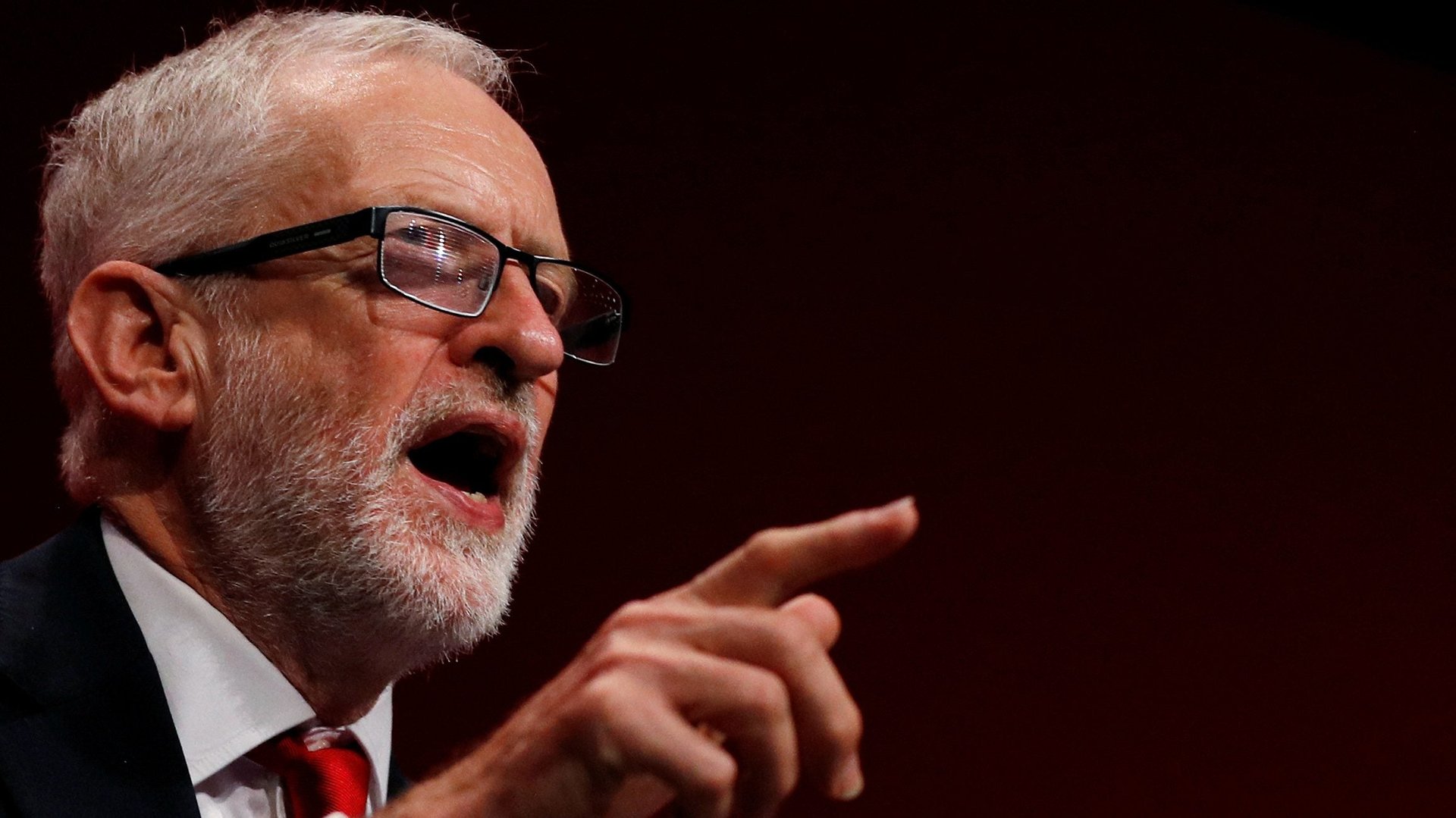

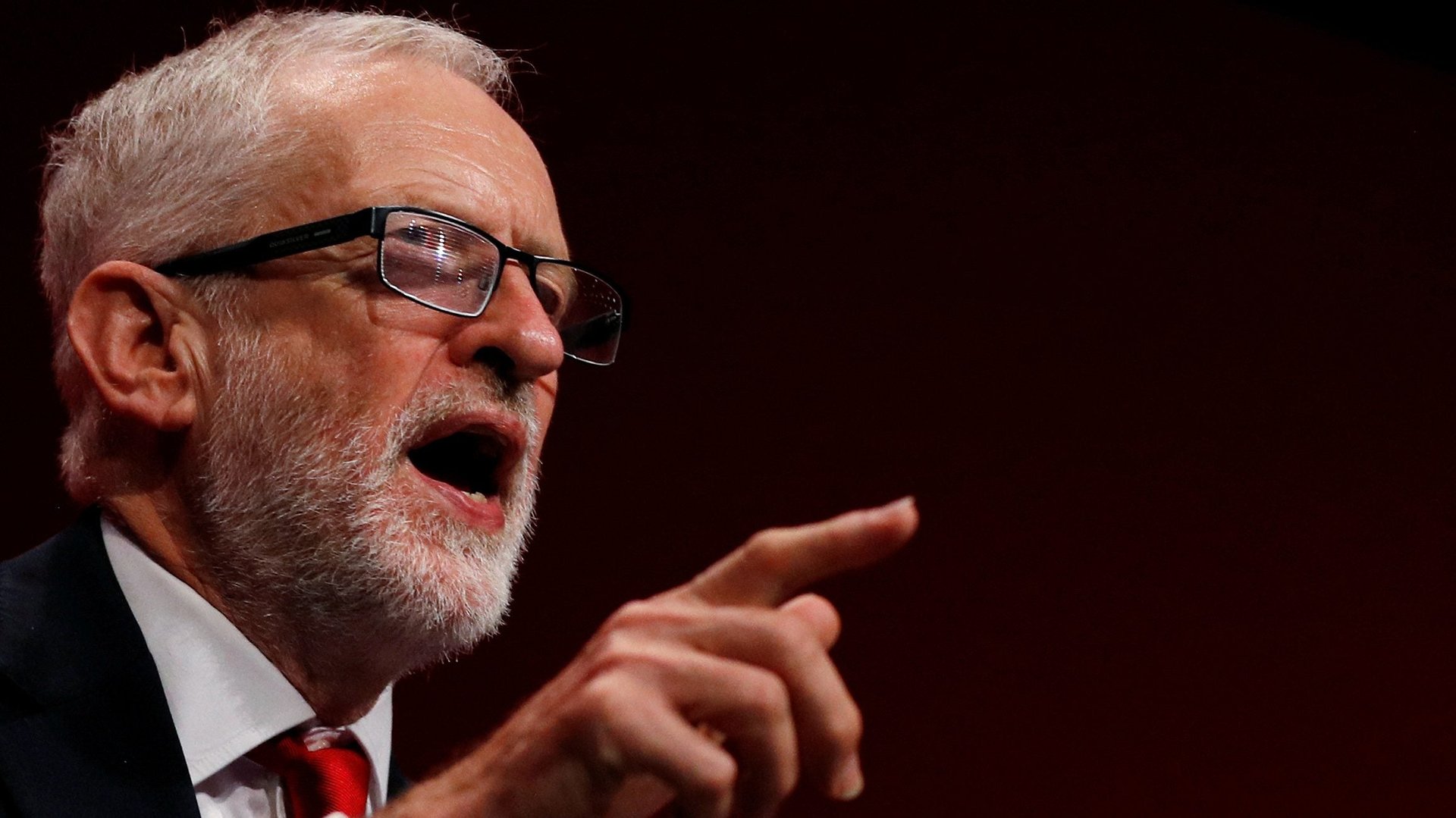

The Labour party has angered some British Hindus over its views on Kashmir

They say all politics is local, but the upcoming UK general election on Dec. 12 has gone global.

They say all politics is local, but the upcoming UK general election on Dec. 12 has gone global.

Amid a divisive campaign that’s already been marred by accusations of antisemitism, the left-wing Labour Party has reportedly angered some British Hindu voters over its stance on the situation in Indian-administered Kashmir.

At the party’s conference in September, Labour passed an emergency motion (pdf) calling for humanitarian and international observers to enter Kashmir, a disputed, Muslim-majority region of India that the government of prime minister Narendra Modi stripped of its independent status in August. Kashmir is currently under military lockdown.

The Labour motion condemned the “enforced disappearance of civilians, the state-endorsed sexual violence of women by armed forces, and the overall prevalence of human rights violations in the region,” as well as “the house arrest / imprisonment of mainstream politicians and activists and restrictions on journalistic freedom.” This angered India’s ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, as well as Hindu nationalists who support the government’s unilateral action in Muslim-majority Kashmir. They point out that Kashmiri separatists and militants have spread terror throughout the region and regularly attack and kill other Kashmiris. Experts argue that the dispute over Kashmir largely comes down to a dispute between Hindus and Muslims.

There has been a backlash to Labour’s conference motion. The chairman of the influential charity Hindu Council UK said in an interview with BBC Radio 4 that most Hindus were “very upset and very angry,” and reports have emerged that Kapil Dudakia, a Hindu businessman with ties to the Conservative Party, may have targeted British Hindus with WhatsApp messages discouraging them from voting for Labour.

This puts the party in a difficult spot. Ethnic minorities in Britain overwhelmingly back Labour, according to the Runnymede Trust (pdf), a think tank focused on race. But the category of “ethnic minority” encompasses many diverse sub-communities with divergent political interests. For example, several wards whose populations are predominantly of South Asian origin voted for Brexit in 2016, even though ethnic minorities as a whole voted to remain in the EU.

The Trust’s latest research shows that the support of British Indians for the Labour Party has remained relatively stable in the past decade, at close to 60%. But it’s worth noting that a subset of this population, British Hindus, has increasingly supported the Conservative Party, in a trend that predates this latest incident: While 30% of the British Hindu vote went to the Conservative Party in the 2010 general election, 40% of it did in 2017.

Polls conducted by the think tank British Future (pdf) estimate that ethnic minority voters cast about one in 10 votes in the 2015 General Election, representing about 3 million voters. And according to research from the poverty-focused Joseph Rowntree Foundation (pdf), “Hindus are the most likely to vote of all the religious groups common in the South Asian electorate,” which makes them important constituents for every party.

With an election looming, Labour has tried to do damage control. Party chairman Ian Lavery wrote a letter in which he backtracked on some aspects of the emergency motion, stating that the party is “fully aware of the sensitivities that exist over the situation in Kashmir.”

“We recognise that the language used in the emergency motion has caused offence in some sections of the Indian diaspora, and in India itself,” he wrote. “We are adamant that the deeply felt and genuinely held differences on the issue of Kashmir must not be allowed to divide communities against each other here in the UK.”

Labour is not the only party that has seen tensions emerge in recent weeks over Kashmir. Last month, an unofficial delegation of more than 20 members of the European Parliament (MEPs) traveled to the Indian-administered part of Kashmir on a controversial, government-sponsored trip. A British Liberal Democrat MP, Chris Davies, was invited, but his invitation was reportedly rescinded when he demanded to be allowed to travel freely throughout the region. He criticized the trip as “a PR stunt for the Modi government.”

The complexity of this debate highlights the global nature of British society ahead of an important election that could help determine the country’s future. Great Britain may be an island, but as this controversy over Kashmir shows, it is not immune to events happening more than 4,000 miles away.