The brain is the final frontier of our privacy, and AI is about to breach it

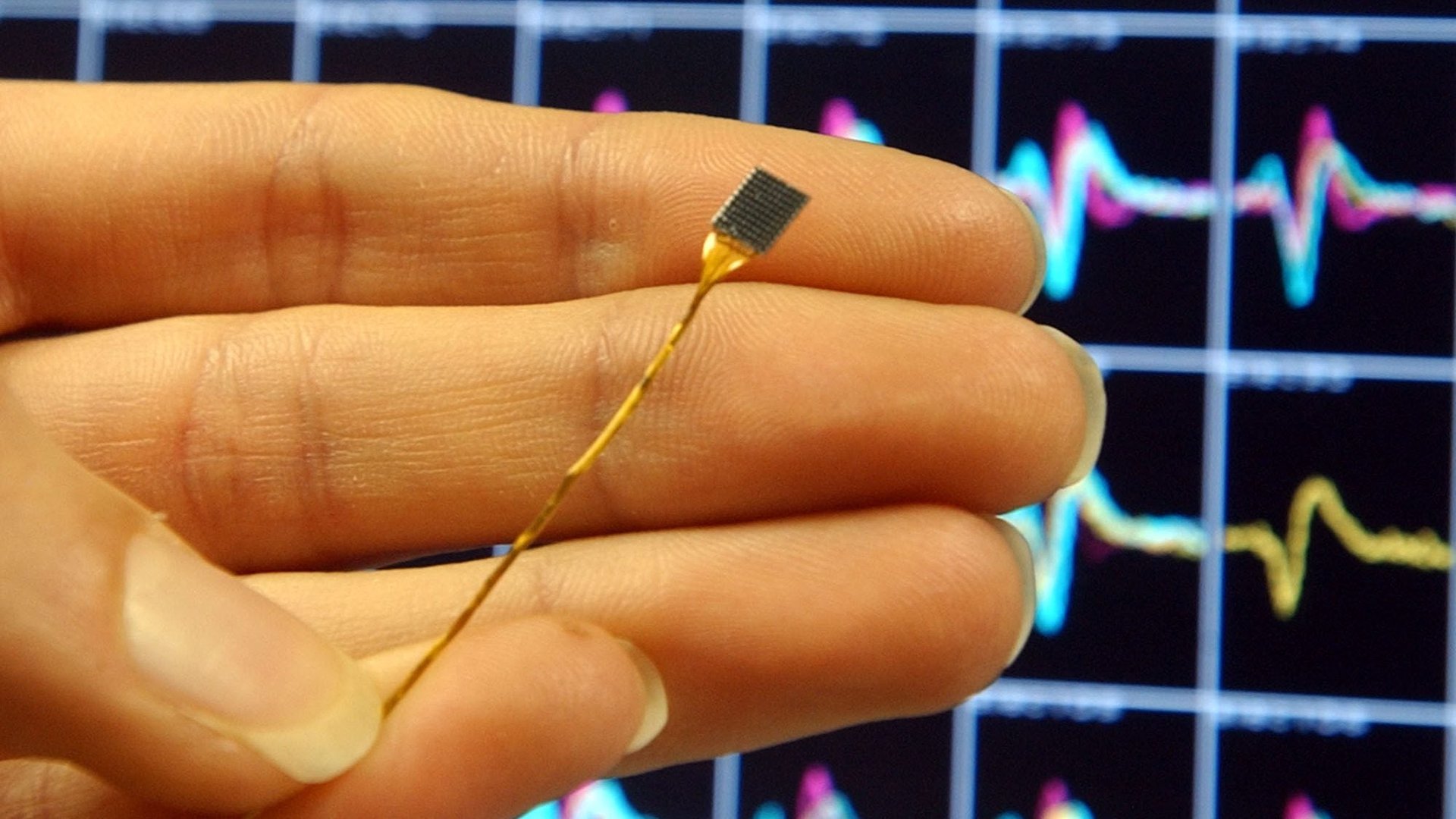

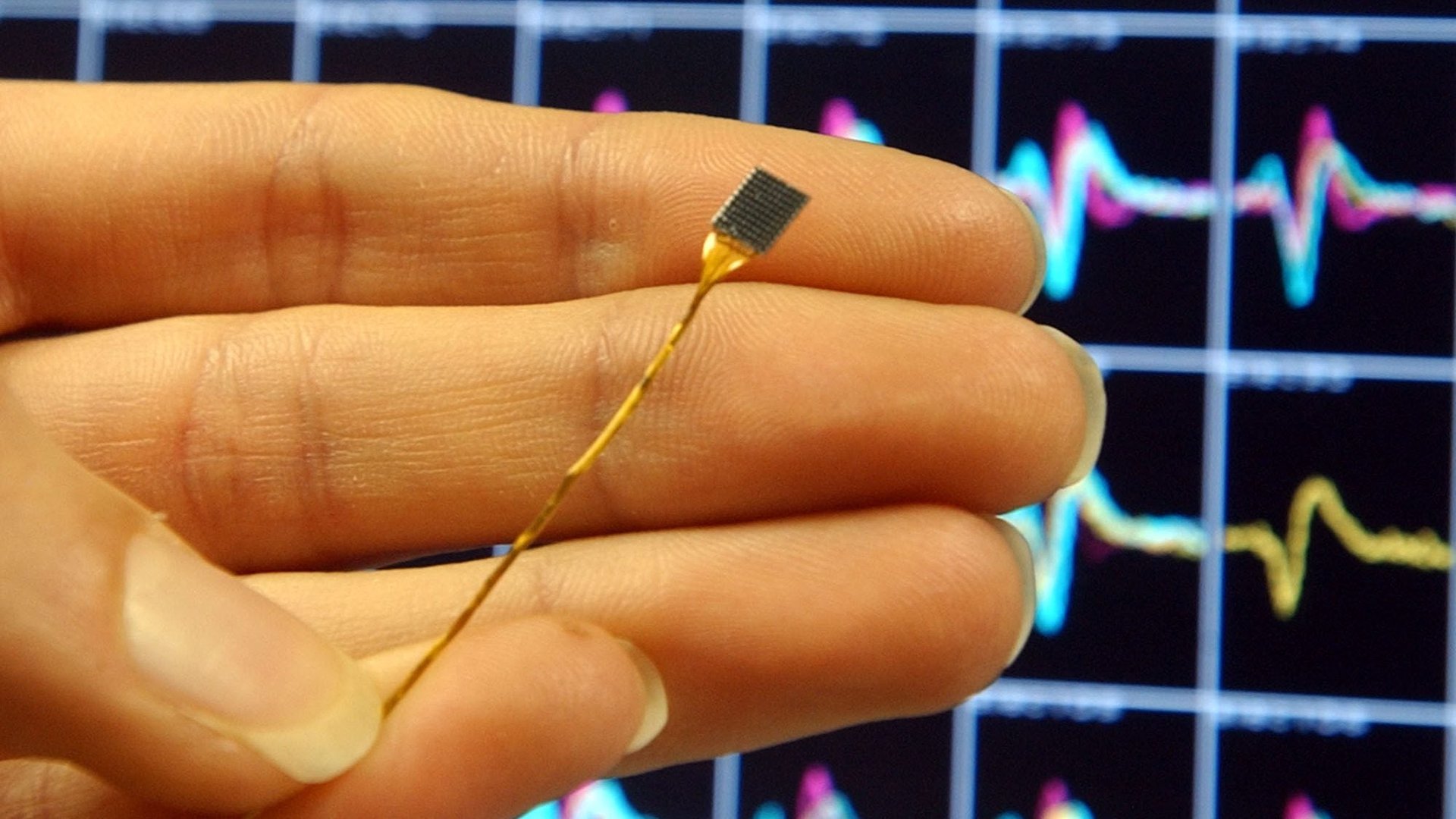

As most people know at this point, connecting our brains to machines is no longer theoretical science fiction.

As most people know at this point, connecting our brains to machines is no longer theoretical science fiction.

In fact, it could be transforming how we communicate as a species. It could even usher in the age of telepathy: Recent developments in brain-machine interfacing highlight its benefits, from treating mental health conditions to controlling objects with the mind, such as wheelchairs and robotic prosthetics.

With devices supercharged with artificial intelligence and, potentially, the computational power of quantum computers, technology could cognitively emancipate millions, if not billions, of people around the world.

AI-powered brain-interface technologies could make people smarter by helping them make better decisions, improve working memory, and process more information more efficiently.

An AI-infused brain would truly revolutionize how, and how quickly, we learn by making it possible to upload knowledge of a number of domains directly to our brains, including in high- skill fields such as engineering, law, medicine, and science.

It could marriage human creativity with the processing power of AI, thus bringing cognitive superpowers to every person on the planet and unleashing a new era in human productivity.

How smart is too smart?

But what happens when everyone is equally as smart as everyone else? How do we value skilled labor that is potentially readily available for anyone, anywhere?

According to the market theory of wages, how much someone gets paid is in part determined by the number of workers available and the number of workers needed for a job. Meaning AI-powered brain-interfaces could upend the fundamentals of market economics.

Lawyers and doctors are typically paid more than manual laborers because of the relative shorter supply of lawyers and doctors, which is in part due to the number of years of training required to enter those professions and the corresponding value society attributes to those skills. But what will happen to their wages once the market is faced with an abundance of skilled labor? If anyone is able to upload legal or medical know-how to their brain and know just as much as the professionals in those fields, why pay a professional a higher wage?

Of course, certain skills, such as strategic judgment and contextual understanding, may be difficult, if not impossible, to digitize. But even the games of chess and Go, both complex games that require strategic decision-making and foresight, have now been conquered by AIs that taught themselves how to play—and beat—some of the best human players.

The technology’s potential for emancipation and human advancement is immense. But we—entrepreneurs, researchers, professionals, policymakers, and industry—must not lose sight of the social risks.

Cyborg security

The biggest issues facing the nascent brain-interface industry are security, surveillance, and privacy. How to protect the brain from corruption, viruses, and remote control will redefine cybersecurity as a whole as it morphs into the cyborg-security needed to shield the brain from foreign invasion.

Instead of hacking into our computer mainframes, malicious actors would be able to manipulate people for financial, political, or even romantic advantage. Fake thoughts or fake memories may cause people to act in ways they otherwise wouldn’t.

The brain, as the final frontier of one’s privacy, will undoubtedly come under attack. Mental data collection efforts—or methods to collect data from one’s thoughts—will be able to mine our minds for our deepest desires, whether conscious or unconscious. Regulation—of access, quality, and security—will therefore play a central role in how we develop, deploy, and protect these technologies, without stifling innovation.

Transparency will be another major issue. It seems logical that people should disclose when they use these AI-powered brain-interfaces. You may have to ask your doctor whether the advice she gives is based on her human knowledge and experience, or some type of human-AI mix. Again, the question arises of how to ensure regulation without censorship. Where to draw the line and how to divorce the human from the artificial may become increasingly difficult to determine, as technological permeation accelerates into the human mind.

Breeding futuristic know-it-alls will also impact our perception of status and power in society. If you can do any job you’d like, and know anything about everything at the tap of your temple, our perceptions of job hierarchy and social status, especially in knowledge fields, will likely shift more decisively from what one knows to what one does with that knowledge.

Education, and educational institutions, would need to adapt accordingly. If knowledge can be uploaded overnight, what will the students of the future do in school? How will universities cope with this influx of already knowledgeable students? How would they be tested?

The knowledge-based economy may give way to one that values creativity and interpersonal skills over everything else, freeing people to make new connections and discoveries to resolve human, social, scientific, and commercial problems, and to discover new fields of inquiry that are currently invisible to our biological minds.

Biased data fed directly into the minds of thousands of people could also amplify structural inequalities across society by creating psychological bubbles that reinforce, or exacerbate, existing biases or create new ones. Who will be the gatekeepers and curators—the cognitive publishers, the knowledge suppliers—of these mental feeds? And how will trust be brokered?

This could easily lead to new social barriers, unless robust legislative and ethical frameworks can be implemented to protect against these risks.

A super class

As with any new technology, the cost of cutting-edge AI-powered products are likely to be prohibitively high.

This runs the risk of creating a new super-class of people who can forever change the structure of a meritocratic society.

To prevent this from happening, industry leaders need to find a way to provide technology that is affordable and accessible so that cost is not a discriminatory barrier.

As the technology we use—and how we use it—changes, entrepreneurs need to proactively lead the debate by proposing innovative solutions in anticipation of some of these problems. At the very least, industry, government, and civil society should develop an ethical framework to guide the development and use of AI-powered brain-machine interfaces.

Ultimately, these new technologies force us to think more deeply about the nature of the human condition. They may mark the evolution of a species that has survived precisely because of technological innovation and adaptation. Or, they may mark a more sinister turning point, where social and cultural norms were disrupted to the detriment of social equality.

As with all technology, the devil lies in how we—humans—decide to use it.