Why it’s more demanding to work for a company without a traditional hierarchy

Working without a manager might sound like a dream but the reality is that it’s often much more demanding. As companies like Zappos and Medium adopt self-governing structures, flat management is piquing the interest of myriad organizations—though it’s not entirely new.

Working without a manager might sound like a dream but the reality is that it’s often much more demanding. As companies like Zappos and Medium adopt self-governing structures, flat management is piquing the interest of myriad organizations—though it’s not entirely new.

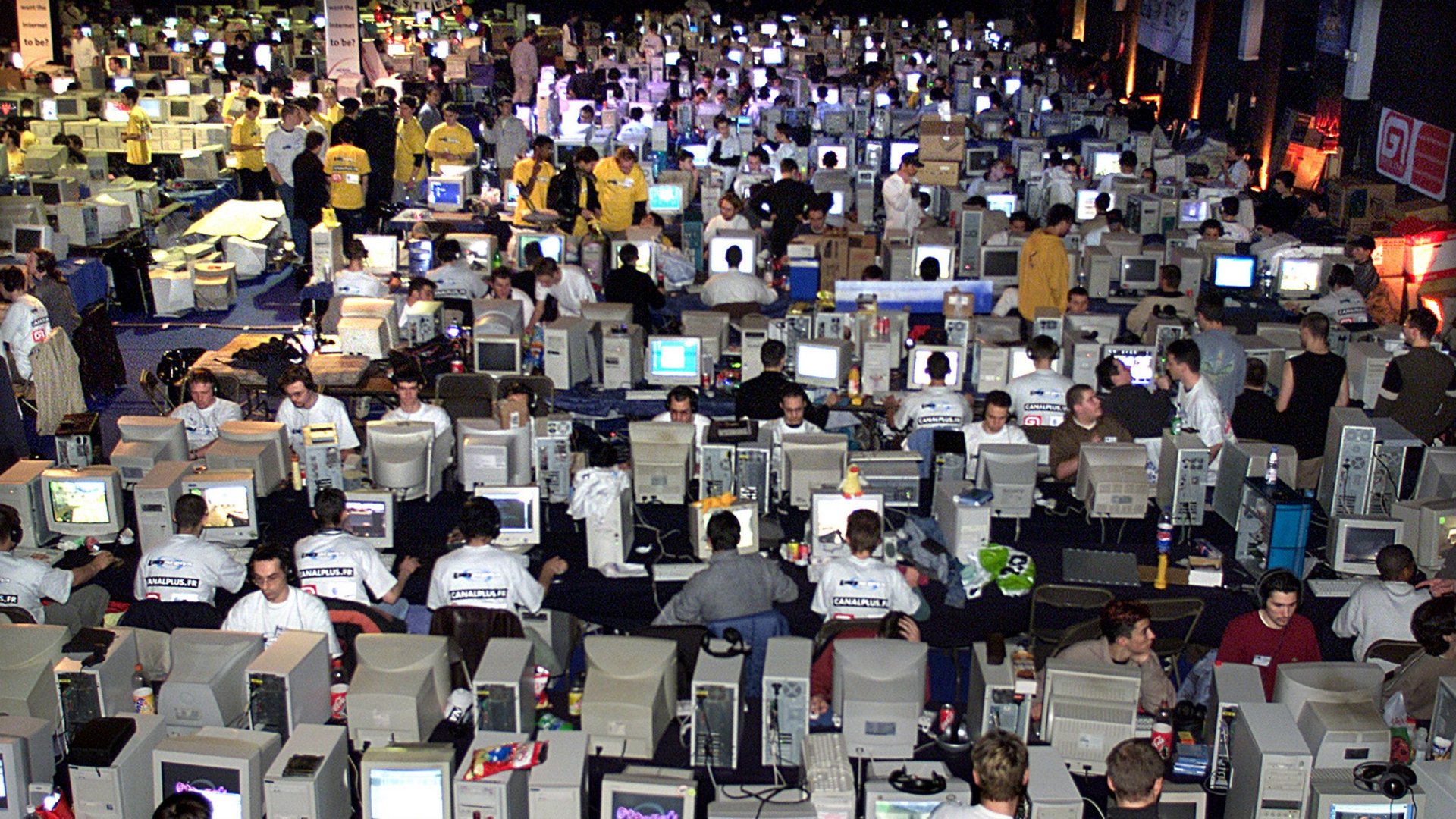

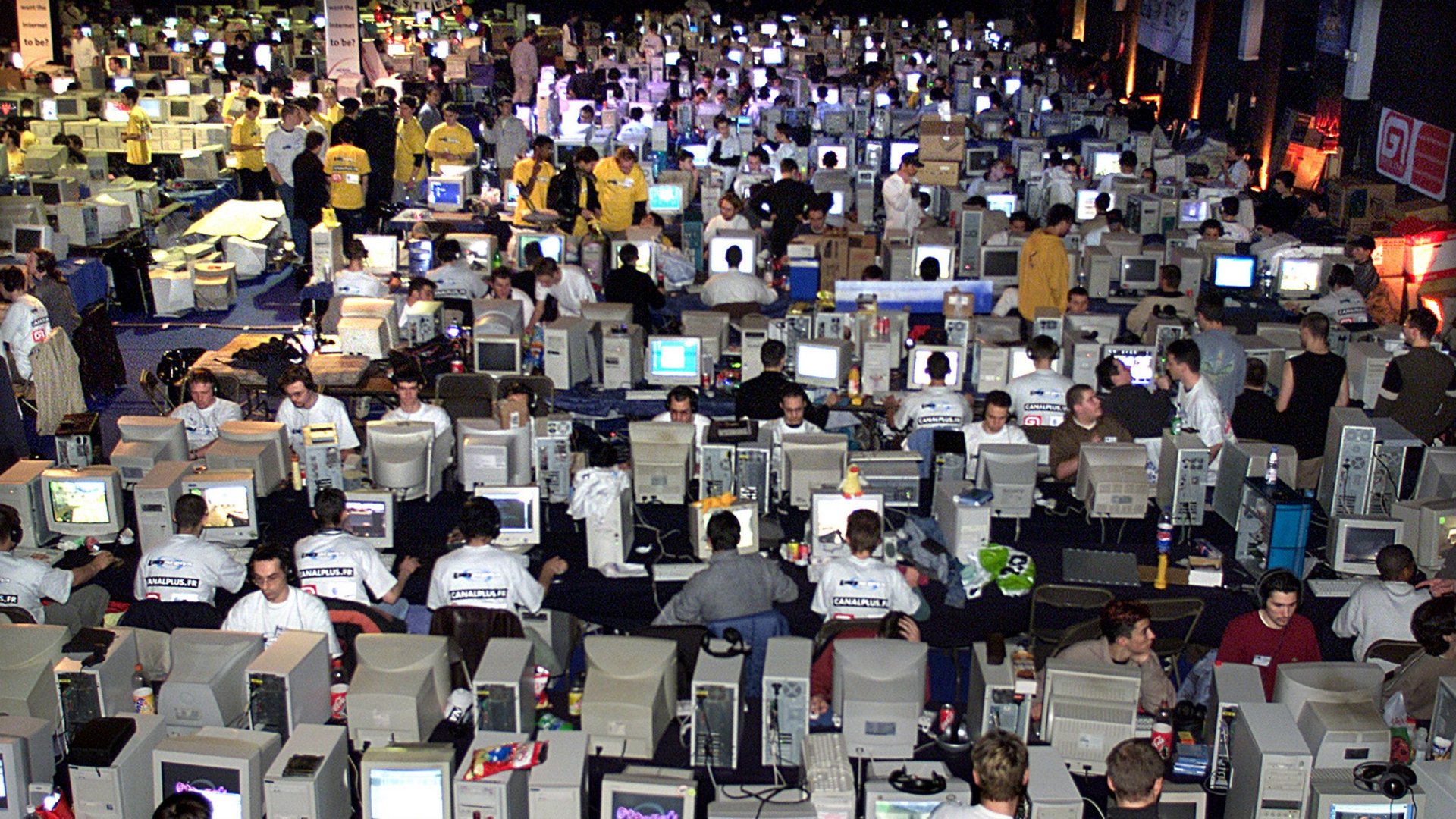

One of the most successful companies to pioneer a self-governing model is Valve, the Bellevue, Washington software company best known for games like Half-Life and Portal. Founded in 1996 by a team of former Microsoft employees, Valve doesn’t prescribe to any one model.

“A lot of companies get started and have innovative ideas about the product or service they want to bring the customers,” says Greg Coomer, who was part of the founding team. “They pour their inventiveness into that product or service. They don’t try to innovate in the design of the company they’re starting to be, specifically tailored to the product or service they’re trying to create. We knew we wanted to build a software company that would always be innovative.”

They decided the best way to do that was with a manager-less culture. “In hindsight, our co-founder Gabe [Newell] was running an experiment in this direction back at Microsoft,” Coomer tells Quartz. “The interesting part of that group was lack of hierarchical organization. People didn’t rely on a structure that was so typical at Microsoft. Flatness helped with getting the work done. So we came to believe the flatness was a critical part of putting each individual in touch with customers. And it’s really proven out.”

But it takes some getting used to a culture without managers, especially if you’re new. Valve’s company handbook, Welcome to Flatland, describes it this way:

Deciding what to work on can be the hardest part of your job at Valve. This is because, as you’ve found out by now, you were not hired to fill a specific job description. You were hired to constantly be looking around for the most valuable work you could be doing. At the end of a project, you may end up well outside what you thought was your core area of expertise.

It takes a lot of discipline to run the company this way, says Coomer, especially now that Valve has more than 300 employees. “Many of us feel like it would be a giant luxury once in a while to have somebody tell us what to do.”

When employees have so much autonomy, it’s crucial to hire the right people from the start. Mike Arauz, a partner at Undercurrent, a corporate strategy consultancy based in New York City describes the firm as “an island of misfit toys. We have PhDs, people from journalism, psychology, every industry you can imagine. The commonality is people who have deep expertise and are also laterally obsessed.” Valve has a term for these types of hires: “T-shaped” people, those who are both generalists and experts.

“In the last couple years it’s really become a theme that all of our clients are struggling with the same thing,” says Arauz. “Their operating system isn’t in tune with this day and age. Companies like Google, Amazon, Uber, Quirky, are all pretty agile with lean processes. A lot of our work in the last couple years has been studying those companies.”

Aaron Dignan, Undercurrent’s CEO, adds: “This seems to be a reflection of the broader takeover of digital technology, as it pervades every aspect of how organizations operate. The next generation is beyond simple divisional structures. It’s organized around the user and the work—the frequent shipping of better and better products—and companies need to find structures that support that.”

After hearing Ev Williams talk about how he’s using Holacracy to run Medium, Undercurrent decided to test it out with its 25-person firm, and relay what they learn to corporate clients like GE and American Express.

“We came at it as a small, nimble company by nature,” says Dignan. “We were attracted to the idea of continual change and evolution. Let’s try something quickly and see if it works.” So far Holacracy has worked for them, although they’ve modified the system to fit their company. (The folks at Medium have also said that it can sometimes feel too dogmatic.) “We’re actively discussing how to adapt these principles and other models such as agile software development and lean manufacturing to help clients, and ourselves become more responsive,” says Arauz, adding that Spotify’s “Scaling Agile @ Spotify” manifesto has been really influential. While there isn’t necessarily a trend toward self-regulating companies, he says, there is a push toward streamlining and simplifying organizations.

Ethan Bernstein, assistant professor at Harvard Business School, agrees. “There are a growing number of business leaders who are using controlled experiments to observe outcomes when they make certain changes to their organizations,” he tells Quartz. “Because they can observe cause-and-effect and correct course, they are willing to try some pretty daring things.”

While flat management might come more naturally to tech companies, larger corporations are feeling the need to innovate internally. Zappos recently gained attention for being the largest company to adopt Holacracy—a system without internal job titles, managers, and traditional hierarchy—for its 1,500 employees.

There’s no data on what percentage of companies are self-governing, “but it would likely be really, really small,” he says. “This would be especially true if you were looking at number of companies, given the ~6M companies in the US.”

Still, there are a number of companies that are also experimenting with self-governing structures around the world. Several French companies are practicing Holacracy, and in Japan, online and mobile gaming developer Kayac is known for its non-hierarchical structure.

Bernstein says that there are some commonalities between these companies. “At Kayac, they have a lot of coders working for them. Valve is also primarily made up of coders. Coders seemingly understand this sort of system better than non-coders.”

He also says that even without managers, these companies aren’t leaderless. “The difference between self-governed organizations and typical hierarchical organizations isn’t about having a person to look to,” says Bernstein. “It’s just not always going to be the same person.”

“We’ve demanded of ourselves that we’d never hire someone who we wouldn’t want to be our boss, at the highest and lowest levels,” says Coomer, who adds that hiring is done by consensus, and any employee can be involved in the process. “It’s extremely difficult.”