The future of Uber is basically Amazon

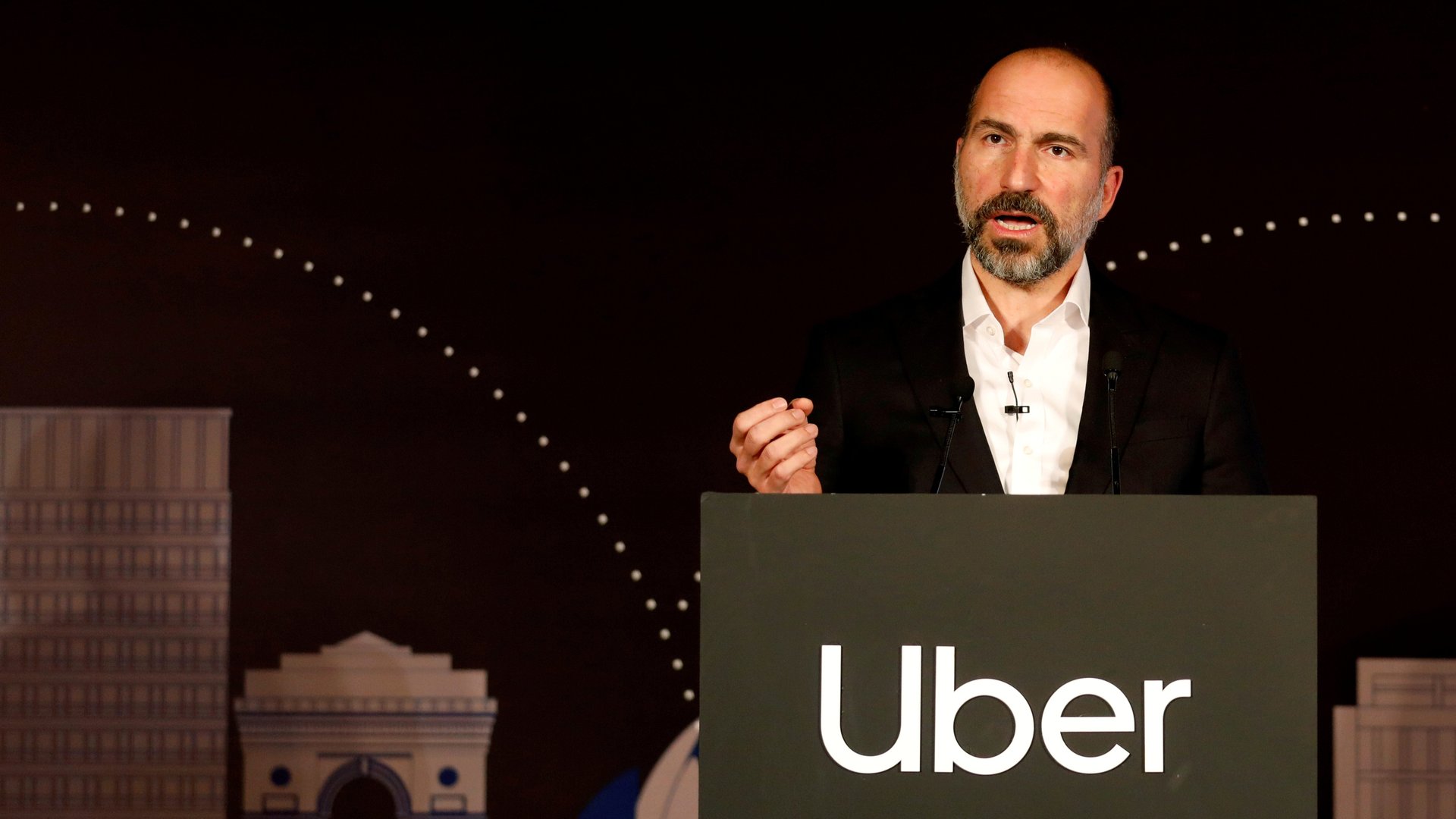

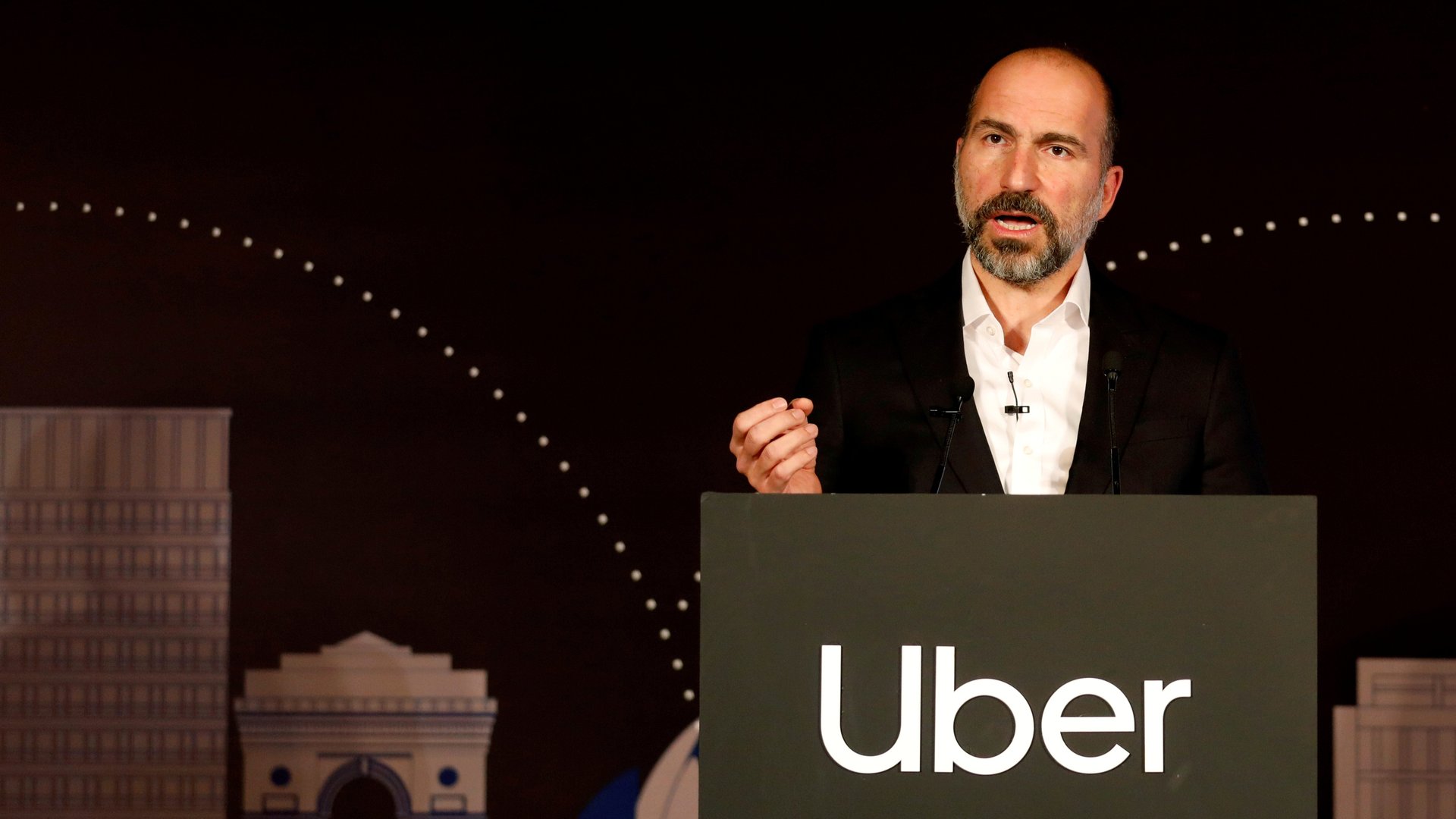

If the first big revolution of our modern tech era was digital, prompting companies like Google to go and organize the world’s information, the next revolution is playing out more broadly, with companies integrating the digital and physical realms, and trying to figure out how to do so in a responsible, profitable way. That’s the view of Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, who described the landscape, and Uber’s role in it, in a Dec. 4 talk hosted by the Economic Club of New York.

If the first big revolution of our modern tech era was digital, prompting companies like Google to go and organize the world’s information, the next revolution is playing out more broadly, with companies integrating the digital and physical realms, and trying to figure out how to do so in a responsible, profitable way. That’s the view of Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, who described the landscape, and Uber’s role in it, in a Dec. 4 talk hosted by the Economic Club of New York.

“Where we are fundamentally different from almost any other company is that we operate at the intersection of the digital and physical,” said Khosrowshahi.

Only this isn’t exactly true. Long before Uber, which was founded in 2009, there were companies like Amazon, and a host of other, less durable e-commerce retailers. When Jeff Bezos started his online bookseller in 1994, the idea of advertising products and taking orders over the internet was still new. But the delivery of those products was very much a physical undertaking.

To anyone interested in the future of Uber, Amazon offers another important precedent, one that Khosrowshahi recognized as a model for his company: In the same way that Amazon is no longer just about books, Uber is no longer just about booking a car ride.

Khosrowshahi wants Uber to be a marketplace, offering virtually any form of transportation—whether that’s an Uber, taxi, subway, scooter, or flying vehicles—but also helping you decide the best way to get to your destination. He sees the variety of transit options (with the goal to make them all shared, and all affordable to middle- and upper-middle-class customers) as part of a solution to worsening traffic congestion in large metros.

He also sees Uber as a growing marketplace for delivery. Earlier this year, Uber started integrating its Uber Eats food-delivery service with its main app, giving users the option to choose rides or Eats when they open the app. In October, the company acquired a majority stake in Cornershop, an online grocery service in Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Toronto. And in November, Uber signed a deal with American cooking-show star Rachael Ray, with meals from her recipes delivered exclusively via Uber.

But the delivery marketplace won’t begin and end with food, Khosrowshahi said. The goal, he told the New York audience, is to be able to send food from any restaurant in under 30 mins, with the opportunity to “extend [the delivery] model to every single local retailer” in New York City.

While Uber wants to model itself after Amazon, it differs in that it wants to build partnerships rather than simply create the technology needed for the ecosystem, Khosrowshahi said. While it takes “very structured and disciplined technology work in order to externalize a bunch of technology that you’re building yourself,” building partnerships requires a “different attitude,” he said. “It is much easier to essentially build out the service itself than work with partners.” But he said Uber has “a commitment to build out a whole ecosystem.”

Eventually, he expects the food-delivery experience will be more focused on the food and the restaurants it came from, and less on the service that delivered it. He compares it to the evolution of television—how we first focused on the tv but now we’re more fixated on the show rather than the box (or flat screen) we watch it on.

Khosrowshahi’s lofty goals are currently grounded by a slew of obstacles. Uber has yet to make money, and increasing regulatory pressures are threatening its business model. But the new ventures he envisions for the company will create “new earnings opportunities” for drivers—and, investors no doubt hope, for Uber itself.