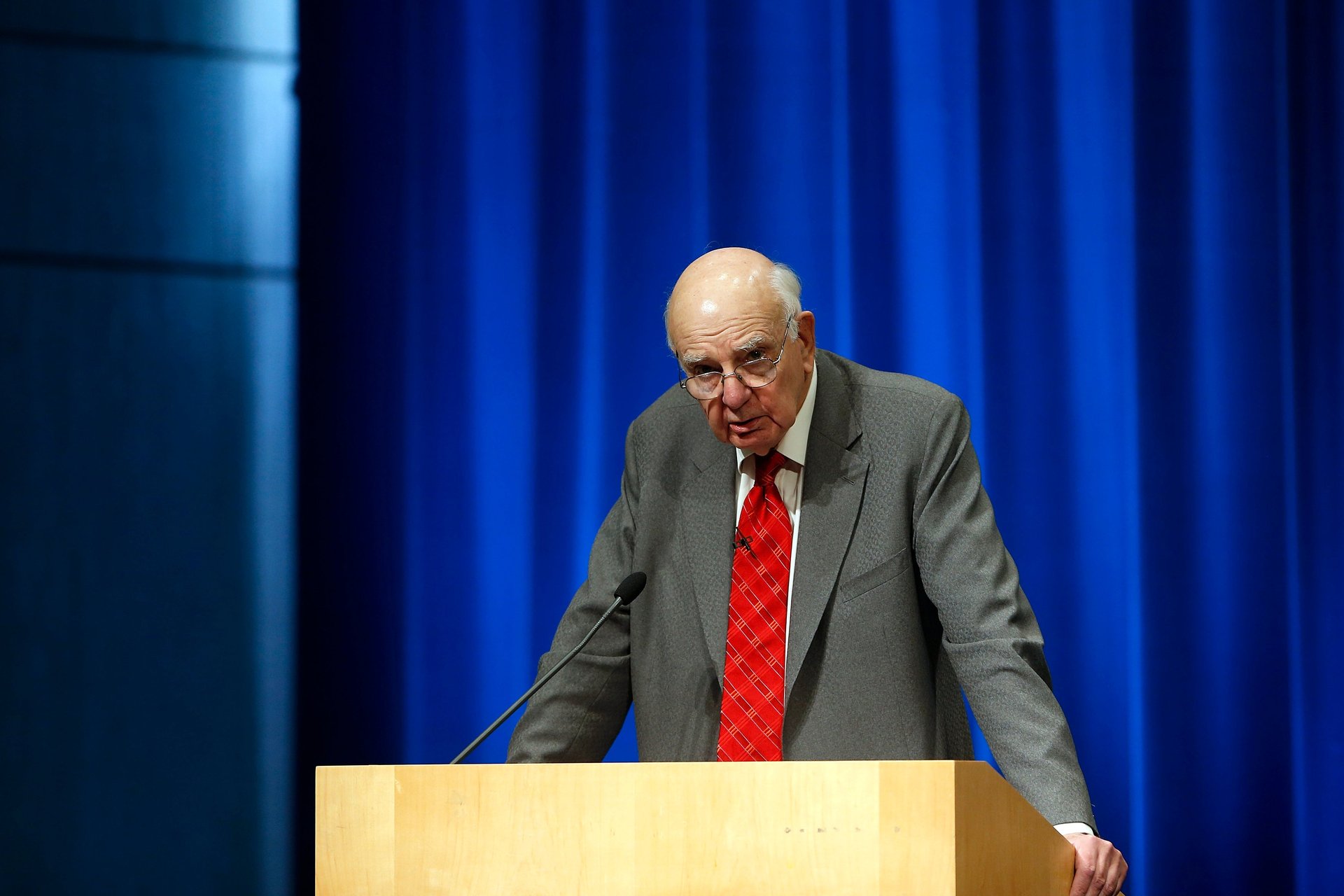

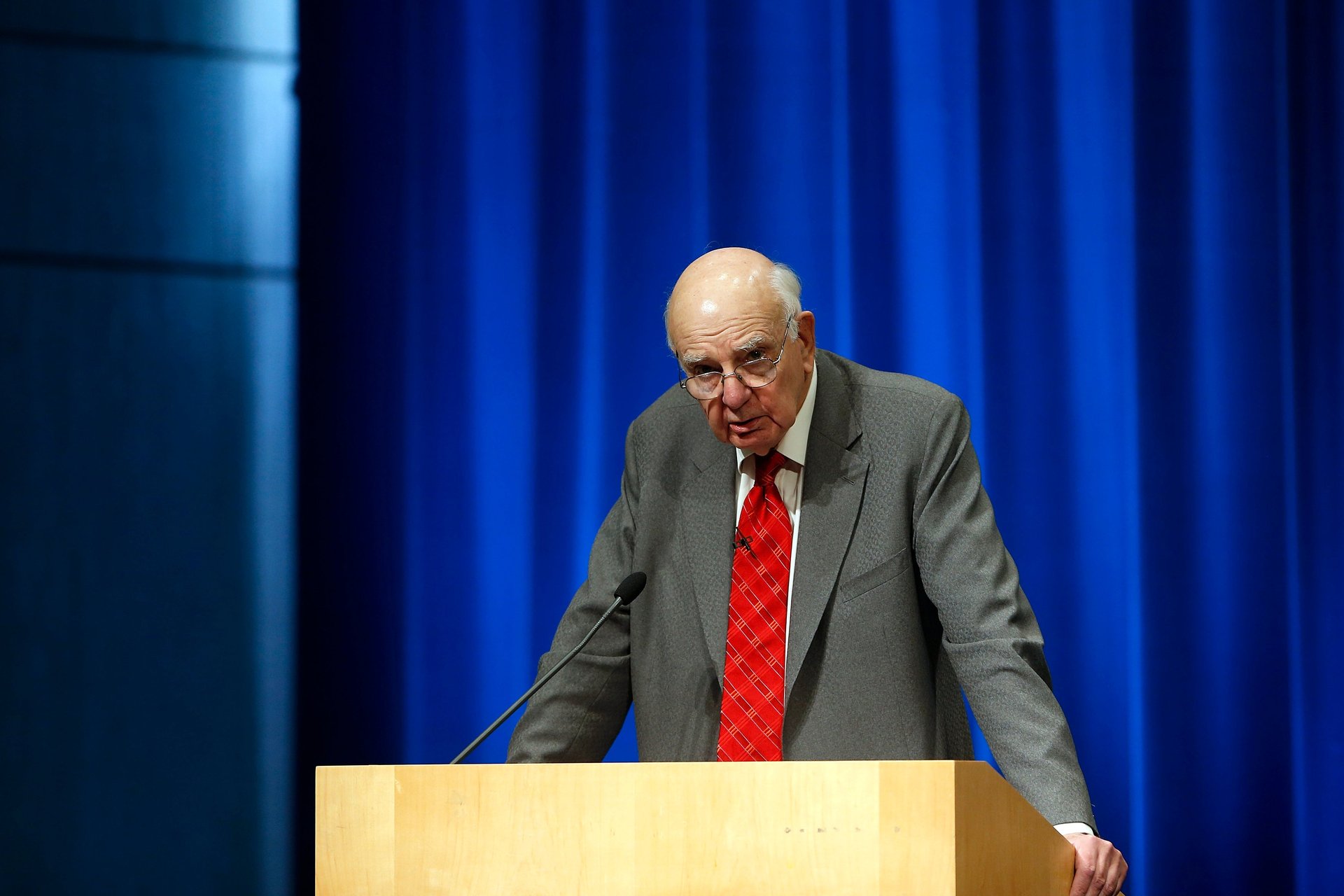

They don’t make central bankers like Paul Volcker anymore

I once met a former Federal Reserve governor who worked with Paul Volcker and told me the only way to win over the towering former Fed chairman was to prove to him they were tough enough for the job. Toughness mattered a lot back then, when the Fed was willing to do what it took for the good of the economy in the long run, even if that meant policies that were extremely unpopular in the short run.

I once met a former Federal Reserve governor who worked with Paul Volcker and told me the only way to win over the towering former Fed chairman was to prove to him they were tough enough for the job. Toughness mattered a lot back then, when the Fed was willing to do what it took for the good of the economy in the long run, even if that meant policies that were extremely unpopular in the short run.

The 1970s were an exceptionally bad time for US inflation. It was astronomical by today’s standards—as much as 15%—and unpredictable. It made consumption and investment, let alone retirement, much harder. Volcker took over the Fed in 1979 and promptly hiked interest rates above 20%. A recession followed. So did criticism from labor and business leaders. Farmers on tractors came to Washington and surrounded the Fed. The brouhaha may have cost Jimmy Carter re-election to the White House. The new president, Ronald Regan, had his chief of staff, James Baker, demand that Volcker lower rates.

But Volcker held firm. He broke inflation before he lowered rates. This was followed by decades of low, predictable inflation, which continues to this day.

Economists came to realize a big part of what drives inflation is expectations. If people expect steady low prices, that expectation can become self-fulfilling. Unions will demand smaller wage increases, firms will print lower prices on their menus. But for these expectations to hold, people need to believe someone will keep inflation low. Volcker, who died on Dec. 8 at age 92, proved to the markets that he would do whatever it took to battle inflation. This afforded great credibility to the Fed, and to Volcker’s successors, and gave American consumers decades of stable prices. The following image may be Volcker’s greatest professional legacy:

It’s hard to fathom how important this price stability is. A new generation of investors and market commentators, who have barely any memory of what Volcker had to do, have no concept of inflation and the harm it can cause. They even make fun of people who worry about inflation, calling them cranks. But the last quarter-century has been a historical anomaly, largely thanks to Volcker’s courage. Today, when everyone freaks out about rates going up 0.25% while unemployment is below 4%, it’s hard to imagine another Volcker at the Fed, openly defying the White House or the whims of the stock market.

Odds are when someone is nominated to be a Fed governor now, no one asks them how tough they are, or how tough they’re willing to be.