Recession watch: Why this cycle may not mirror the past

As growth and corporate earnings slow, investors are dusting off their old case studies for late-cycle investing. While that worked in the past, there are twists to today’s market that require new strategies.

As growth and corporate earnings slow, investors are dusting off their old case studies for late-cycle investing. While that worked in the past, there are twists to today’s market that require new strategies.

Macroeconomic growth patterns are typically orbital, and today’s environment feels like a late-cycle economy. Growth is above the norm, and inflation is reaching its target. In the past, this would mean a recession is coming.

But this cycle is different. A decade full of extreme and unusual policies has shaped today’s market. Fiscal stimulus, debt levels, deficits, and demographics are all in the mix. Taken together, these could extend the endgame features of the current cycle for longer than usual, which means lower returns for longer than expected.

How did we get here?

In 1981, the fed fund rate peaked at about 19%, changing market dynamics for a generation.

First, interest rates and inflation declined for the next 20 years. Then baby boomers entered their prime earnings, which buoyed economic growth and funneled savings into the markets via their retirement plans. Simultaneously, globalization and innovation increased productivity and profitability exponentially. These circumstances increased wage gains, corporate sales, earnings, and, ultimately, the stock market.

By the late 1990s, these fundamental drivers started to run out of steam. Inflation fell to 2%, yields declined by as much as 15%, and the oldest baby boomers started exiting their peak earning period. Meanwhile, China took root as the world’s mass producer, and massive technological advances led to record-high stock valuations.

Then came 2001: The dotcom bubble burst, and the US housing crisis began—leading us to the 2008 global financial crisis. By early 2009, central banks were pumping money into markets to avert a catastrophe.

This was the birth of the Great Beta Trade, when central bank policies drove sustained returns with little volatility. Investors could ride the beta wave effortlessly. Since investment funds with diverse strategies benefited, investors didn’t need to know what was driving performance. And with so much money in the markets, downturns were mild and usually corrected themselves quickly.

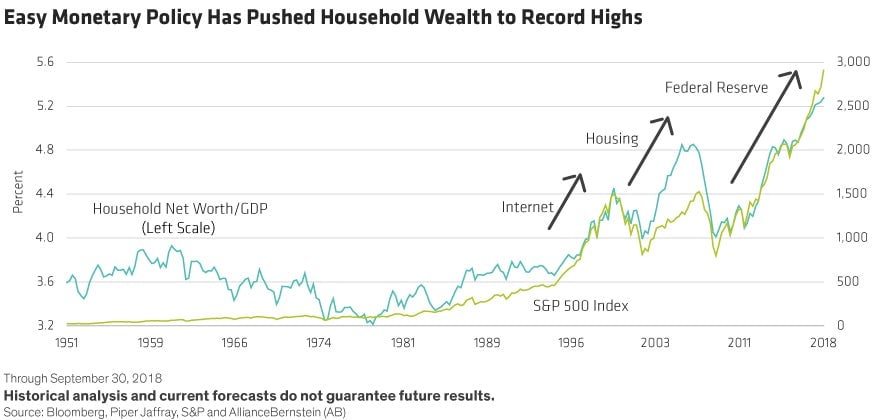

During this time, historically low interest rates were key. Household wealth surged, and low rates helped companies borrow more to support profitability and share buybacks. In the broader economy, consumers could easily finance houses, cars, and everything in between. This all found its way back into the equity markets, where investors benefited from a cycle that continuously powered gains. And in contrast to previous periods, these returns weren’t driven by economic or sales growth, but by cheap borrowing.

That was the problem. Leveraged returns are not sustainable. Investors might have cheered at net margin improvements, but it was really just a prolonged sugar rush, without any sustainable nourishment in the form of revenue gains or economic growth.

What does the future hold?

As all of this comes to an end, return forecasts for the next decade are lower than they were in the past. And to add, there are four more trends contributing to late-cycle uncertainty:

- Fiscal deficit is widening—The US deficit typically narrows when unemployment falls. But recently, the deficit has kept widening even as employment rates increase. This reflects a public spending spree that could have unintended consequences for the stability of the world’s largest economy.

- Debt burden is ballooning—Since the financial crisis, low interest rates around the world have incentivized borrowing. Global debt reached approximately US$178 trillion by 2018, and has surged by 50% over the past decade. Stretched balance sheets could be dangerous if financing conditions tighten.

- Baby boomers are retiring—As baby boomers near retirement, the forecast for market returns is weak, and big corrections are more likely. This will create challenges as funds draw down.

- Geopolitical tensions are growing—From trade wars to Brexit, new risks threaten to create volatility and contribute to the risk of market drawdowns.

What does success look like today?

There’s no precedent in modern financial history to help us navigate these conditions. But by identifying core challenges, we can develop new solutions.

In an era of low returns, elevated volatility, and heightened risk for retirees, controlling the path of returns is key to investing success. It’s not only about how much portfolios return, but also how they generate those returns and hold up during market drops. Investors should pay closer attention to how portfolios are constructed, how their funds’ exposures will behave as the markets eat these challenges, and how equipped managers should invest through uncertainty. Investors can tackle the late, late-cycle. They just have to change their strategies.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations, do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams, and are subject to revision over time.

This article was produced on behalf of AllianceBernstein by Quartz Creative and not by the Quartz editorial staff.