Doctors in Britain say “preventable” air pollution is overwhelming NHS waiting rooms this winter

A group of 175 doctors published a letter in The Times today warning the UK government that air pollution is leading to a spike in respiratory diseases, bronchitis, and pneumonia, straining an already overwhelmed National Health Service (NHS).

A group of 175 doctors published a letter in The Times today warning the UK government that air pollution is leading to a spike in respiratory diseases, bronchitis, and pneumonia, straining an already overwhelmed National Health Service (NHS).

The “severe pressures in the winter months are being exacerbated by preventable causes” like air pollution, reads the letter, which was spearheaded by the British Lung Foundation and the Clean Air Fund. “This is a public health crisis.”

Air pollution and health

Air pollution is toxic to the human body. Pollutants in the air—microscopic in size, most thinner than a single human hair—can slip deep into the respiratory and circulatory systems, damaging the lungs, heart, and brain. The most well-known of these particles, PM2.5 and PM10, are made up of harmful compounds like arsenic, lead, and black carbon, and have been linked with an increased risk of stroke, cancer, miscarriage, and asthma and autism in children.

Statistics show that these particles tend to peak in winter, a time when children and adults are likelier to develop respiratory infections like bronchitis and pneumonia. In its latest report (pdf), the NHS said it had seen an increase in emergency department attendance for cases of acute respiratory infections, bronchiolitis, flu-like illnesses, and pneumonia.

The doctors’ letter points out that these “winter conditions” can be exacerbated by air pollution. For example, children’s risk of being hospitalized for respiratory conditions goes up on highly polluted days.

“There are no beds”

Britain’s NHS is over-subscribed and under-funded. Recently statistics found that patients were waiting longer in emergency rooms and for important treatments like hip replacements and hernia repairs. In these conditions, the doctors warn in their letter, emergency rooms and doctors’ offices are ill-equipped to handle a spike in patients.

“Thousands of children and adults are in hospital or waiting rooms with conditions such as respiratory diseases, bronchitis and pneumonia,” the letter reads, “but they would not need to be there if air pollution was reduced.”

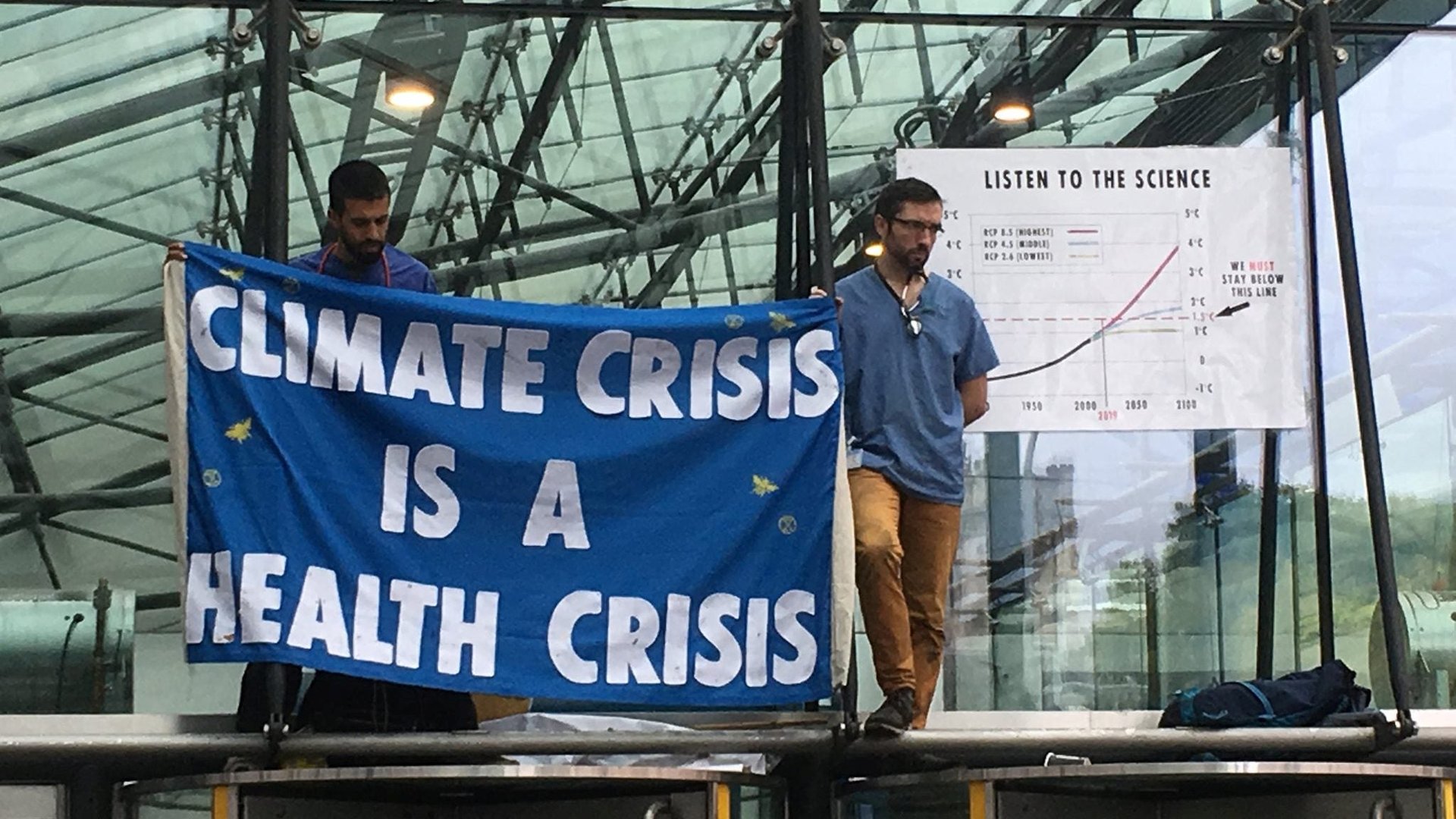

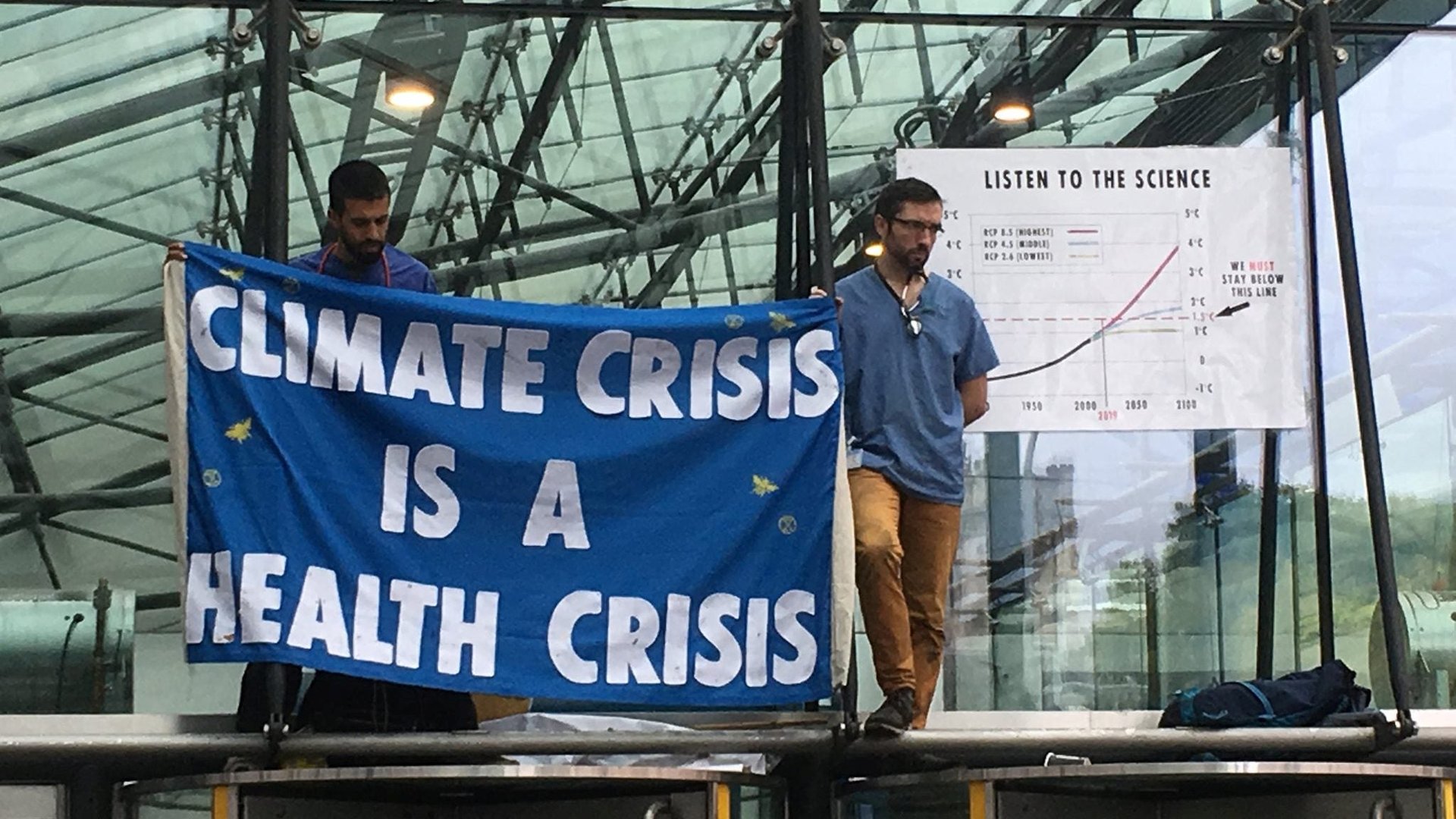

William Stableforth is a gastroenterologist and medical consultant at Royal Cornwall Hospital, where he sometimes treats respiratory infections in the emergency room. He is a member of the activist group Doctors for Extinction Rebellion and a signatory to the Times letter. He says hospitals like his are “operating at 110% capacity,” so this spike “just compounds the problem of overcrowding and lack of beds.”

The situation has been worse this winter, says Stableforth, “in that we’ve been told, probably more often than usual…that there are no beds. It used to be sort of occasional but now it’s frequent.”

When there are no beds, he says, “some people go home a bit earlier than we would like them to go home.” Addressing air pollution “could take some of the pressure off,” he adds. Hospitalizations for respiratory conditions in adults and for pediatric asthma or reduced lung function would go down, he says, freeing up beds for more urgent cases. An analysis by King’s College, London of pollution and hospitalization data from seven cities in the UK suggests that more than 1,000 hospital admissions for respiratory diseases could be avoided each year if higher air pollution days were lowered.

Air pollution has decreased slightly in major cities like London recently, thanks in part to measures put in place to encourage cycling and walking and discourage driving (especially diesel cars). But air quality remains a big problem in the UK, where pollution levels routinely exceed limits set by the World Health Organization (WHO). Courts ruled that the government’s air pollution policy was insufficient on three occasions.

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said the government is “committed to cleaning up our air as well as setting strict new laws on air quality,” and pointed to a promise made by the Conservatives during the election to spend £33.9 billion ($44.3 billion) more per year on the NHS by 2024.

In the letter, doctors urge prime minister Boris Johnson to commit more resources to tackling air pollution and to commit to a legally binding target to meet WHO guidelines for PM2.5 pollution by 2030.

“People are dying,” says Stableforth. “That’s not okay. Somehow, we’ve normalized it, and we need to un-normalize it and call it out as unacceptable.”