How Adderall could actually hurt your kid’s grades

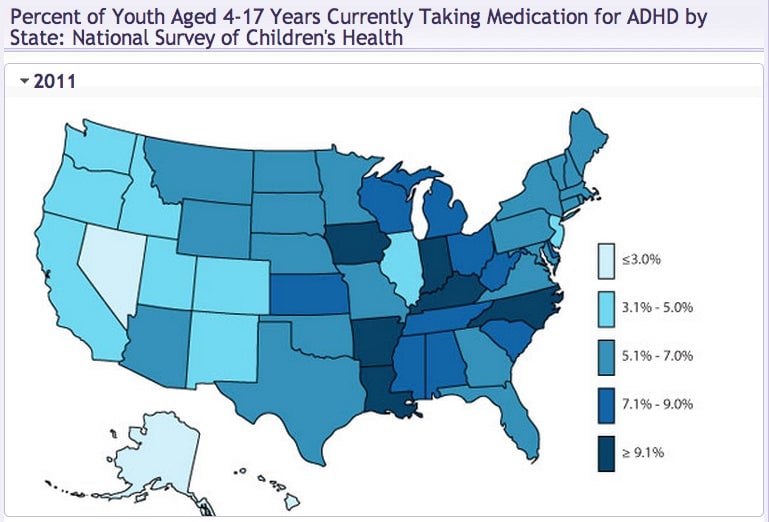

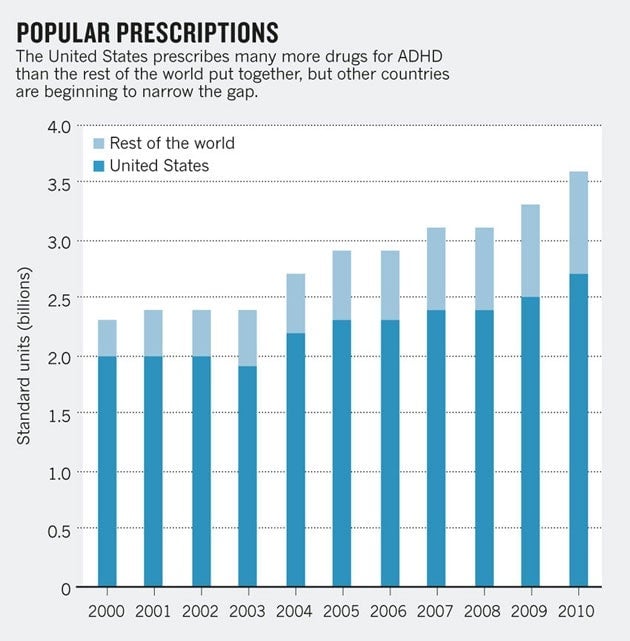

More than one in twenty American children between the ages of 4 and 17 are medicated for attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—up nearly 500% since 1990. Drugs like Adderall and Ritalin have a reputation as “good-grade pills” and “cognitive enhancers” that produce near-immediate improvements in the ability of children to pay attention in school.

More than one in twenty American children between the ages of 4 and 17 are medicated for attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)—up nearly 500% since 1990. Drugs like Adderall and Ritalin have a reputation as “good-grade pills” and “cognitive enhancers” that produce near-immediate improvements in the ability of children to pay attention in school.

The thing is, studies tracing the impact of ADHD meds report no improvement in academic performance in the long term, as Nature reports in a new review of existing research, and kids taking the drugs are in some cases more likely to drop out of school.

It’s not clear why this would be happening. The glib answer would be pharmaceutical marketing blitzes have duped us into believing the products’ brain-boosting properties. But a study from the 1970s, which predates big-budget ad campaigns for the stimulants, points the way to a more persuasive—and and potentially more worrying—explanation.

When the researchers in that study asked parents and teachers to evaluate ADHD children’s scholastic performance before and after medication, they found that though the children’s grades stayed the same, adults believed they improved, reports Nature.

Worse, parents’ and teachers’ inclinations to mistake manageability for academic improvement could actually be exacerbating children’s academic problems. A recently published long-term study of ADHD medication in Quebec (pdf, p.25, registration required) found that, despite consistent Ritalin dosages, there was “little overall improvement in outcomes” in the short term—and in the long term, more of these kids dropped out of school and reported unhappiness.

“By making children less disruptive, ADHD medication could decrease the attention that they receive in the average classroom and reduce the probability that the child receives other needed services,” wrote the study’s authors.

Again, that’s just a possibility. But as Princeton economist Janet Currie, one of the study authors, told Nature, the tendency of adults to overlook struggling students who seem to be doing okay might explain why medicated students in her study ended up performing worse than their distracted-yet-unmedicated classmates.