France’s high-speed rail network is worth $2 billion less than it was a year ago

As thrilling as it is to whizz through the countryside at up to 320 kmh (199 mph), France’s economic malaise means that fewer people are willing to pony up for the priciest routes on the famous TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) network.

As thrilling as it is to whizz through the countryside at up to 320 kmh (199 mph), France’s economic malaise means that fewer people are willing to pony up for the priciest routes on the famous TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) network.

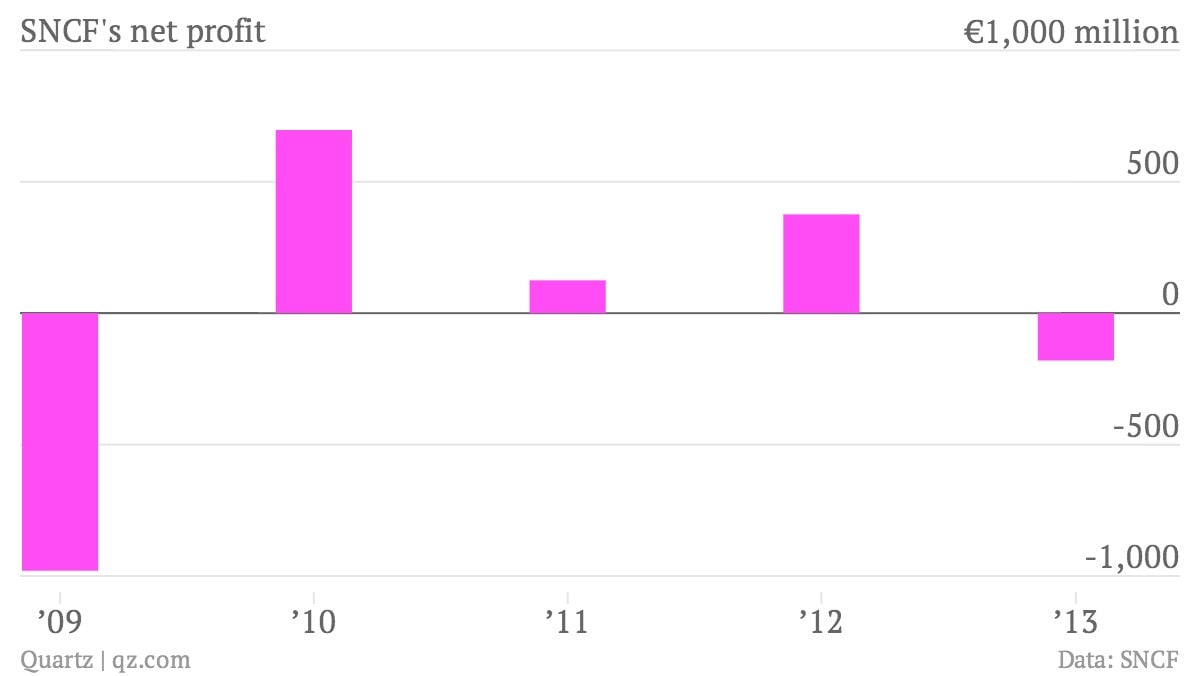

SNCF, the state-owned French railway company, slipped into the red last year (pdf) and recorded a net loss of €180 million ($246 million) for 2013, reversing a profit of €376 million in the previous year—pain largely due to an eye-watering €1.4 billion writedown in the value of the high-speed long-distance train network.

TGV ”is not sufficiently profitable to cover the carrying amount of its fleet and its renewal,” SNCF admitted. In addition to the economic slowdown, the company cited steep running costs and competition from low-cost flights and cars as two of the factors responsible for the TGV’s flagging fortunes. The network’s property, plant, and equipment is judged to be worth nearly $2 billion less, in accounting terms, than it was at the start of last year.

Operating profits at SNCF Voyages, the long-distance division, fell by 31% in 2013, driven by a fall in traffic from business travellers. The local train network saw revenues hold up a bit better than its long-distance sister company, but profits fell at roughly the same rate; freight, meanwhile, recorded a smaller loss (€117 million) than the year before, but a loss all the same.

The bright spots last year for the SNCF group—a sprawling conglomerate with €32 billion in revenues and nearly 245,000 employees—were only partly related to trains. The star performer was its Gares & Connexions unit, which helps design stations and collects rent from retail tenants; this division saw profit more than double, in part because some pieces of the group’s infrastructure unit were reassigned to it. Speaking of infrastructure, what remained of this unit, which maintains tracks and develops railway management systems, also held up reasonably well, with a small drop in profit on a modest gain in revenues.

This year, SNCF expects a “slight turnaround,” but passenger volumes on the TGV are forecast to keep falling. To boost overall revenues, which were stagnant in 2013, the company’s infrastructure and services divisions are pitching for projects outside of France. It is also trying to squeeze as much ancillary retail revenue out of stations as it can muster, which will help cushion the blow from weaker domestic traffic.

As one of the world’s high-speed rail pioneers, it is understandable that SNCF’s engineering advice and expertise is sought by rail operators around the world. But set against the struggles of its core business at home, this puts it in a somewhat strange situation: France’s state railway company is doing pretty well, aside from the business of actually running trains.