Why dictators make terrible conversationalists

Dictators are not ideal guests at dinner parties. They shout and pound on the table too much, jostling the wine glasses. They’re always making weird declarations like “Banish napkins” or else ordering children to chisel flattering busts out of radishes. Make one little comment that rubs a dictator the wrong way, and the whole evening can get a little murder-y.

Dictators are not ideal guests at dinner parties. They shout and pound on the table too much, jostling the wine glasses. They’re always making weird declarations like “Banish napkins” or else ordering children to chisel flattering busts out of radishes. Make one little comment that rubs a dictator the wrong way, and the whole evening can get a little murder-y.

And there’s another reason why totalitarians capable of horrific human rights violations are a real hosting nightmare. As Stephen Miller explains in his 2006 book Conversation: A History of a Declining Art, dictators are rotten conversationalists.

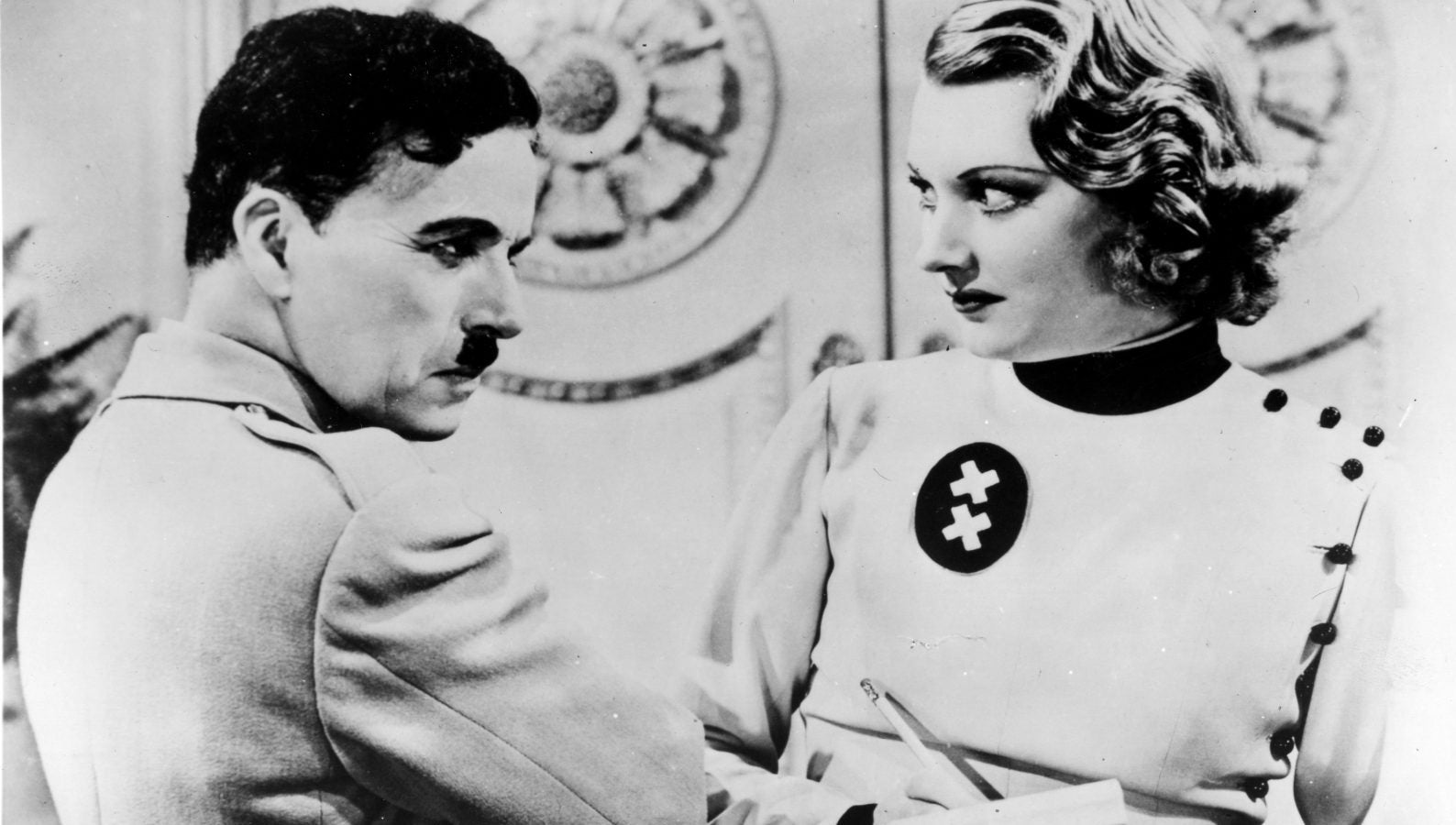

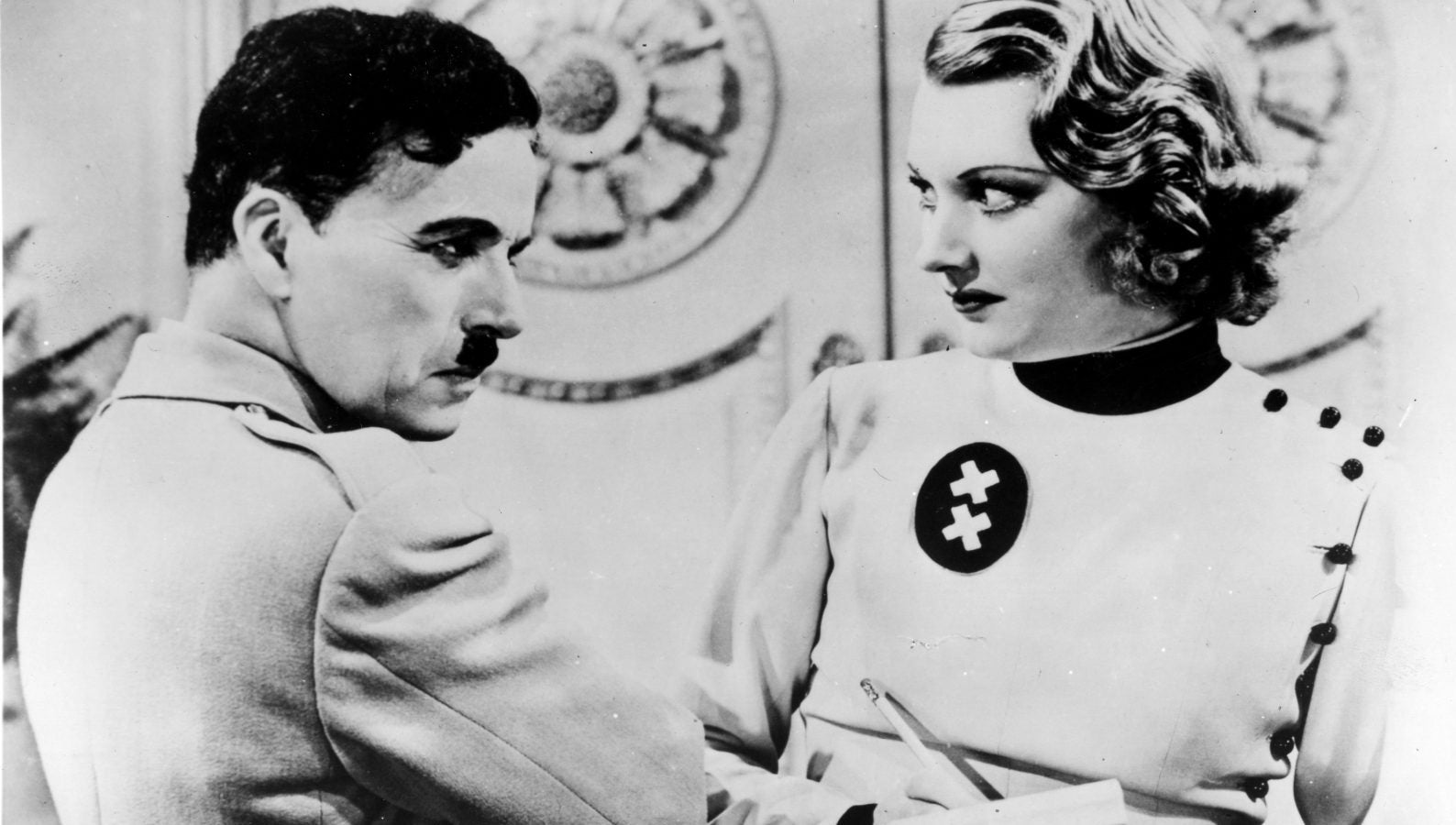

Hitler, for example, was guilty of both mass murder and some classic conversational missteps: He repeated himself, and he didn’t let anyone else talk. Miller quotes one of Hitler’s former secretaries, who complained, “Every evening we had to listen to his monologues … It was always the same … On every subject we all knew in advance what he would say. In course of time these monologues bored us. But world affairs and events at the front were never mentioned; everything to do with the war was taboo … In 1944 I sometimes found myself still sitting up with Hitler at 8am, listening with feigned attention to his words.”

Stalin was apparently no better, vacillating between long-windedness and fury: “Ian Buruma speaks of the dinners at ‘Stalin’s many country houses, where the extreme boredom of the Leader’s rambling monologues could instantly turn to panic at the smallest hint of his displeasure,'” Miller writes.

The pattern holds. Napoleon Bonaparte’s “conversation almost always bore the appearance of ill-humor,” the French emperor’s one-time friend Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne writes in his memoirs. During a private conversation in North Korea in 1983, two South Korean filmmakers secretly recorded Kim Jong-il’s “tirade-like monologue,” which dragged on for two hours. With a few exceptions—Mao Zedong was purportedly a “poor public speaker” but “good conversationalist who knew how to put his audience at ease”—dictators seem to consistently, flagrantly violate Emily Post’s conversational rules of etiquette, which hold that a good talk is all about give and take.

If dictators are so bad at talking to people, how do they manage to accumulate power in the first place? It could be that the communication tactics that help them capture the attention of crowds—a forceful manner; a simple message; a narcissistic knack for developing a cult of personality—simply don’t translate to more intimate settings, where curiosity in others and a good sense of humor tend to carry the day.

A recent New Yorker article by Adam Gopnik offers some additional clues. Discussing two recent books on what dictators have in common with one another, Frank Dikötter’s How to Be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century and Daniel Kalder’s The Infernal Library: On Dictators, the Books They Wrote, and Other Catastrophes of Literacy, Gopnik writes that while dictators are “horribly grotesque in most areas, they tend to be good in one, and their skill at the one thing makes their frightened followers overrate their skill at all things, like children of a drunken father who take a small act of Christmas charity as proof of enormous instinctive generosity.”

Often, according to Kalder, that one skill comes down to a proficiency with language. Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, and more all used the written word to help their ideas spread and gain traction, to horrifying effect. This comes as a reminder that linguistic skill is not a moral virtue, whether on the page or at the podium.

Nor is the ability to charm one’s neighbor over appetizers necessarily the sign of a pure heart. Still, one of the slogans Mao used to justify mass slaughter was “The revolution is not a dinner party.” A dinner party, after all, typically involves a lively, free exchange of ideas. For dictators, there’s bound to be something deeply threatening about that.