Social media has become an inclusive alternative to history textbooks

The first time I learned about the historical hardships of Hawaiian Americans was in a TikTok video posted to Twitter. The video, which features a young Hawaiian woman explaining how the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown by a group of American sugar planters in 1893, caught me completely off guard. As someone with a high school diploma and two college degrees, I somehow managed to go through more than two decades of schooling without ever giving thought to the history of Hawaiian people, much less learning about it from my textbooks or teachers.

The first time I learned about the historical hardships of Hawaiian Americans was in a TikTok video posted to Twitter. The video, which features a young Hawaiian woman explaining how the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown by a group of American sugar planters in 1893, caught me completely off guard. As someone with a high school diploma and two college degrees, I somehow managed to go through more than two decades of schooling without ever giving thought to the history of Hawaiian people, much less learning about it from my textbooks or teachers.

Another topic that seemed to blow right by my history classes: Japanese internment camps. This American tragedy recently landed on my radar when this tweet was retweeted onto my timeline:

Sifting through the conversation the tweet inspired, I quickly learned that the camps were established during World War II by US president Franklin Roosevelt and lasted from 1942 to 1945. They seemed to me to be very comparable to the current detention camps at the US-Mexico border, and a real reminder that history can repeat itself—though you might not even realize it if your textbooks failed you like mine did.

Another example comes from Michael Harriot, a senior writer at The Root, who tweeted about the surprised reaction many white people had to the bombing of Tulsa, a horrific, real-life event from 1921 depicted this year in the HBO fictional series Watchmen. Harriot observes that black Americans seem far more likely to have been familiar with the bombing by white vigilantes targeting a black Tulsa neighborhood, suggesting that African Americans are getting their American history elsewhere, outside of the classroom.

For some families, history lessons take place at the dining room table. I didn’t learn about Malcolm X’s legacy or the burning of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” in any of my 12 years of grade school, but instead at home, over dinner, with my mom and dad as the teachers. And when I did learn about African-American history in a formal educational setting, my parents always made sure to give me a supplemental lesson that didn’t palliate the truth as my history books often did.

With the state of the American dinner table being what it is, social media is becoming an important source of these educational conversations, and users aren’t sugarcoating the content. Harriot’s tweet about Tulsa and Watchmen, which garnered a ton of engagement, kicked off a substantial thread, more than two dozen tweets long, about the history of racial injustice and race-based terrorism in America. It notes the little-known fact that black people served in Congress between 1870 and 1898, and describes the massacres that transpired to disenfranchise black voters.

Rewriting history is harmful

Some might argue that social media is a dangerous place to learn about historic fact, given the swirl of half-truths and outright lies that these platforms allow. But savvy readers of online content know there are ways to authenticate the information they come across.

The question is, are we at least as discriminating when it comes to the information we still consume from history books? As recently as 2018, students at a school in San Antonio, Texas, were using the textbook Prentice Hall Classics: A History of the United States, which argued that not all slave owners were cruel, suggesting that “a few [slaves] never felt the lash,” and that “many may not have even been terribly unhappy with their lot, for they knew no other.” The book was last published in 2007.

In 2015, a Texas student flagged a textbook caption in another history book that labeled enslaved people as immigrant workers. And in 2017, a Canadian history book was recalled after public uproar over a line stating that “The First Nations peoples agreed to move to different areas to make room for the new settlements.”

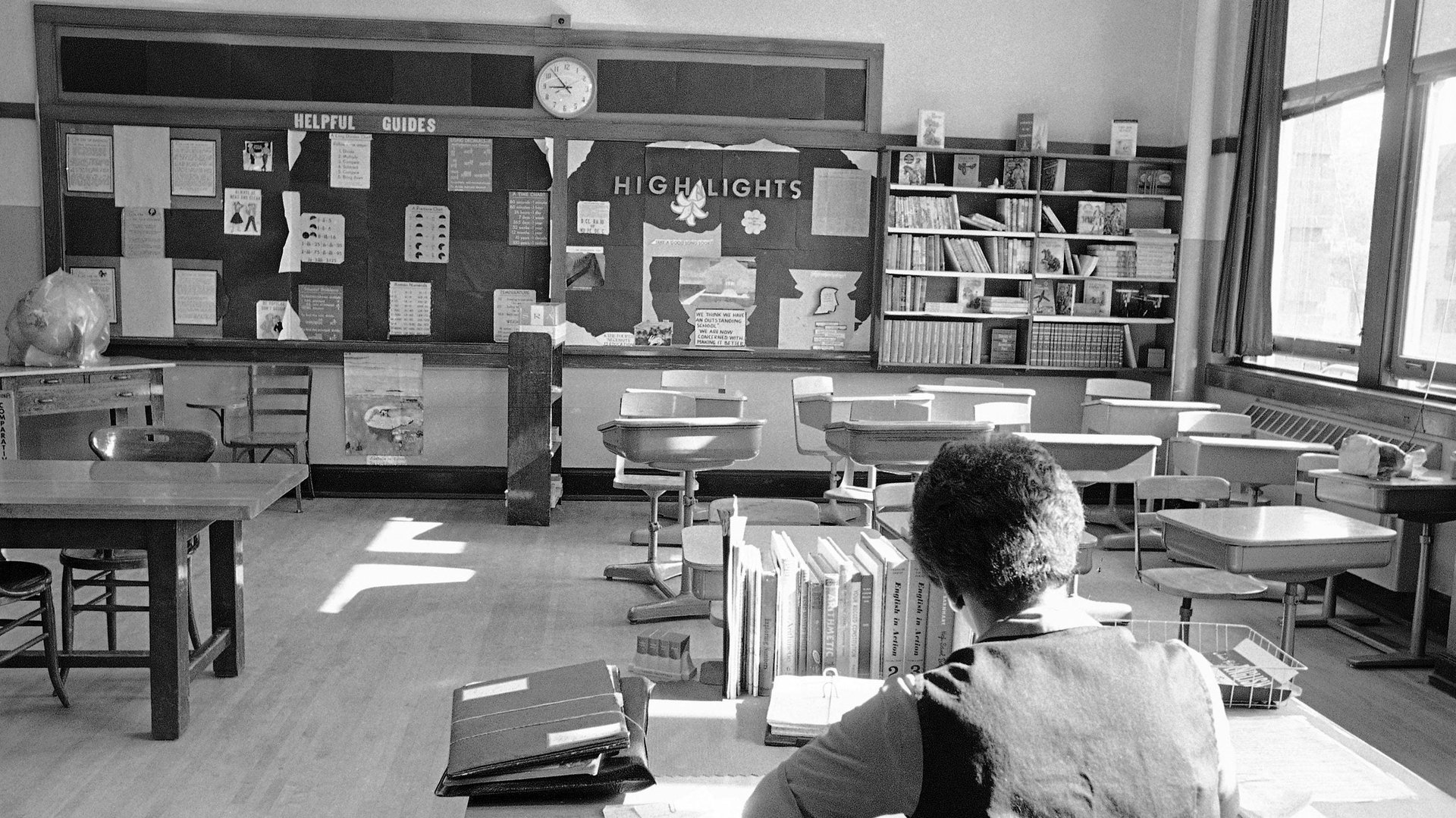

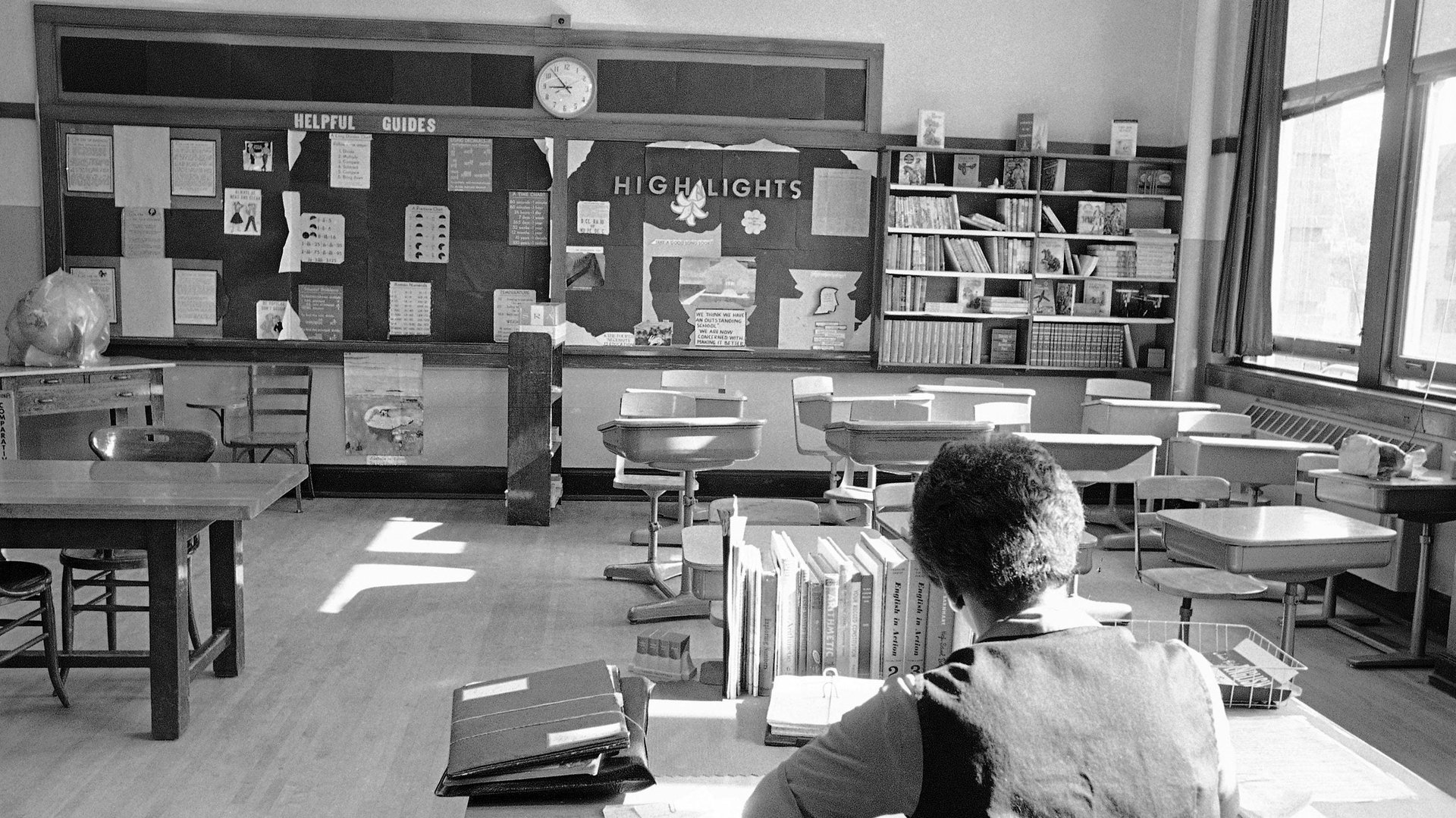

More than 80% of teachers in America’s public elementary and secondary schools are white. What histories are they missing? Which stories are they interpreting based on their own education and identity?

Social media is strewn with educational landmines, but also educational riches. It’s a worthy supplement, or successor, to dinner table conversations where we teach our children what they don’t learn in school. That 52-second video clip I stumbled upon on Twitter gave me a better understanding of Hawaiian history than any of my textbooks ever did—and it suggests there’s a lot more historical content out there for me to discover.