Mormon women are caught between economic pressures and the word of God

For more than 5,000 high schoolers applying to college each year, Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah, checks two critical boxes: It’s an extremely good university, and its tuition fees are just $5,790 a year.

For more than 5,000 high schoolers applying to college each year, Brigham Young University, in Provo, Utah, checks two critical boxes: It’s an extremely good university, and its tuition fees are just $5,790 a year.

But if you’re a Mormon student, there’s another reason to want to attend: It’s the largest and best majority Mormon university in the world. And for women, that comes with an additional perk. “The point of Mormon women going to college is to find a spouse, period,” says Kate Kelly, an alumna of the college who graduated in the early 2000s. BYU is just about the best place to do so, with a student population of 35,000, and a Mormon-majority community that prioritizes marriage and the family unit. Within 12 years of graduating, 84% of BYU graduates are married.

At BYU, the hunt for a spouse touches almost every aspect of student life, says Kelly, who grew up in the Mormon faith but was excommunicated in 2014 over her push for gender equality. It’s the focus of speeches given by religious leaders, meet-and-greet activities, even religious practice, she says. Even at regular compulsory worship, students are split up by marital status—if you’re single and lucky, The One may be sat over in the next pew. The pressure was everywhere: “BYU is just like a dating factory,” she remembers, “but [for women] that was the entire point.”

But while secular women may see education as a route to a more lucrative or successful career, most of BYU’s female alumni never work outside the home, despite having attended a top university. The messaging starts early, Kelly says: Throughout Sunday school and other forms of Mormon education, Mormon girls are explicitly told that their college education is predominantly a back-up, “if ever accidentally your husband were to die or you found yourself in a position where you had to earn a living. But otherwise you are not to use it.” Statistics bear this out: Male graduates of BYU earn 90 times more than their female peers, with a median income of $71,900 by the age of 34. Female graduates, on the other hand, earn on average $800 per year. Even the wage gap at other religious universities is not quite so extreme. Female graduates of Huntingdon University, Baptist Bible College, and Maranatha Bible University earn between about $15,000 and $20,000 a year at age 34. It’s a little more than a third of their male peers’ salary, or more than 20 times more than female BYU grads.

Majority-Mormon neighborhoods in the US closely resemble a 1950s ideal: As a 2015 New York Times investigation observes, “the male-dominated nature of Mormon culture has kept nonemployment rates for prime-age women extremely high—as high, in some areas, as they were for American women in the 1950s.”

But Mormon culture, with its reputation for “family orientation, clean-cut optimism, honesty, and pleasant aggressiveness,” as the historian Jan Schipps puts it, hasn’t always looked like this. As far back as the mid-1800s, leaders in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (commonly abbreviated to LDS) encouraged women to apply themselves to work outside the home. The 19th-century LDS prophet Brigham Young, for whom the university is named, thought women might usefully “study law or physic, or become good bookkeepers and be able to do the business in any counting house, and all this to enlarge the sphere of usefulness for the benefit of society at large.”

As of 2013, however, roughly 25% of Mormon women are in full-time employment, compared to 43% of all women in 2018. That’s because, as the Mormon journalist McKay Coppins writes for Buzzfeed, “for many Latter-day Saint women, staying at home to raise children is less a lifestyle choice than religious one—a divinely-appreciated sacrifice that brings with it blessings, empowerment, and spiritual prestige.”

What gives? Over 150 years, as the pressures on the LDS community have shifted, the church’s official stance on women’s rights and obligations has grown more rigid and conservative, changing female adherents’ opportunities and career prospects in the process.

Updated policies

Founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ roots lie in Christianity. There are still overlaps, including a belief in the the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, but the two have striking differences. Mormonism uses additional scriptures, including the Book of Mormon, and recognizes Smith and other Mormon leaders as prophets. Around 1.5 million members of the church live in Utah, out of 6 million nationwide, with an additional 10 million overseas. Many have converted to the religion after encountering enthusiastic young Mormons; missions, in which LDS members bring the good news of prophet Smith to every corner of the globe, are strongly encouraged by the church.

But there’s another important distinction between LDS members and other Christians, which has in turn dictated the changing church policy on women’s roles. For most mainstream Christians, scripture remains as it ever was, with no updates in a few millennia. Mormons see it differently. The church’s president, sometimes known simply as “the Prophet,” serves as a direct line of sorts to God, ready to revise, supplement, or update policies as soon as he hears word. Speaking to CNN, historian Kathleen Flake describes him as “Moses in a business suit—someone who can lead people, write Scripture and talk to God.” Revelations appear on a rolling basis, via the church’s most senior members: In October 2018, for instance, the current leader, Russell Nelson, declared it “the command of the Lord” to use the church’s full name, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when referring to it. Continuing to employ nicknames such as Mormon or LDS would be “a major victory for Satan,” he warned. (Whether for reasons of practicality, forgetfulness, or nostalgia, many members of the church flout these instructions, as do secular news outlets such as the New York Times or CNN.)

If you’re looking for a guide to modern life, the Bible is a challenging place to start. That’s especially true on matters of women’s rights: As a thousand-years-old text, it’s frustratingly oblique on such thorny issues as how women should dress, whether they should work outside the home, and God’s preferred balance of career and motherhood. But for Mormons, His words continue, via the prophets and church leaders, and do indeed address such topics directly. These dynamic revelations have allowed church leaders to communicate God’s word, and fashion an official line on Mormon women’s activities.

“It’s explicit. [The prophets say] point blank that women are not to work outside the home,” says Kelly. “This is not optional. What Mormons say is, ‘The thinking has been done.’”

A 1995 church text called The Family: A Proclamation to the World spells it out plainly: “By divine design, fathers are to preside over their families in love and righteousness and are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families. Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children.” These responsibilities, and the family unit, are sacred.

Pioneers and suffragettes

In the church’s earliest incarnation in the early-to-mid 19th century, women’s labor was critical to the success of the movement and to help “build up Zion,” writes the historian Colleen McDannell in her 2018 book Sister Saints: Mormon Women since the End of Polygamy. These initial LDS women were expected to work—and in almost any field that they chose, from men’s tailoring to studying obstetrics, managing a telegraph office, healing the sick, or even “spawning fish in springs.” Motherhood was valuable, of course, but it was only the start of what these pioneering souls were expected to do to help. Later, these same women would be swashbuckling suffragettes, fighting to be allowed to vote in US elections, in part to preserve their own right to practice “plural marriage,” which many felt was key to building community and sharing labor.

While in the early years of the faith, Mormons generally lived apart from other religions, growing affluence led to greater integration. After abandoning polygamy in 1890, church members grew closer to the US mainstream, adopting a far more traditional approach to the family unit. Women were thus confined to the home. “Since the 1940s, male and female church leaders had been unequivocal in their celebration of motherhood, to the exclusion of almost every other role for women,” writes McDannell. Actively or otherwise, the history of pioneer women was largely forgotten, she explains, with “postwar women […] told to concentrate on home and ward life.”

Though the mainstream started to liberalize in the wake of the war, LDS policy did not. Instead, church publications, fireside talks, and annual meetings allowed elders to speak out against the cultural changes happening in the secular world. Among these voices was Spencer W. Kimball, one of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, an important all-male governing body tasked with receiving and communicating God’s message. In 1973, he became the church’s president and prophet.

Though guidelines for Mormon women’s dress had existed since the 1910s, it was not until the 1950s that Mormon women began to adopt different standards of modesty. In 1951, Kimball, then an apostle, gave a talk on modesty in dress, titled “A Style of Our Own.” After it was reprinted in the official Church News, many Mormon women opted to “kimballize” their wardrobe, lengthening hems or buying little jackets to wear with then-popular strapless dresses. Just one week after the talk, an editorial in BYU’s Daily Universe noted “the noticeable change in attire at the Friday night Banyan Ball” among its female students. Fearing the rise of counterculture, other official pamphlets followed, emphasizing modesty in speech and conduct and a feminine, clean-cut “Molly Mormon” dress style.

Over the same period, church leaders grew more didactic about women’s roles. In the first year of his presidency, in 1973, Kimball sketched out a cozy image of the ideal family unit, which is still cited by church authorities as a key text on “mother’s employment outside the home.” “The husband is expected to support his family and only in an emergency should a wife secure outside employment,” he said, in a fireside talk. “Her place is in the home, to build the home into a heaven of delight … I beg of you, you who could and should be bearing and rearing a family: Wives, come home from the typewriter, the laundry, the nursing, come home from the factory, the café.”

Though these comments resemble so many other conservative critiques of the period, they have far more heft in a Mormon context: Kimball was, after all, speaking as God’s proxy. Rather than suggestions or even commentary, these were divine ordinances from the church’s highest spiritual authority, to be taken as seriously as the words of any ancient prophet.

These comments came at the tail end of a push by church leaders to, as McDannell puts it, “consolidate power, standardize doctrine, and coordinate the various programs” across individual churches. One effect of “correlation,” as it was called, was to limit women’s influence within the church. At this time, most of American Christianity was liberalizing, decentralizing, and opening up to the possibility of women in the pulpit. Mormonism, meanwhile, was doubling down on male leadership and placing more power in fewer hands—and further away from women.

The rest of the US was grappling with scripture of a different sort. Since the early 1960s, the rise of second-wave feminism and of thinkers such as Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan had changed how women thought of their lot—encompassing professional prospects, work-life balance, and what they were prepared to tolerate. Mormon women were not immune to these rumblings—though, like their secular peers, they found little consensus.

In perhaps the best snapshot of these many different views, the independent Mormon journal Dialogue released its “pink issue” in 1971, which dealt primarily with questions of women’s rights. Edited by Claudia Lauper Bushman, an LDS member who would later become a history professor at Columbia University, it paints a picture of women considering their options and obligations from all angles. “Although we sometimes refer to ourselves as the LDS cell of Women’s Lib, we claim no affiliation with any of those militant bodies and some of us are so straight [conventional] as to be shocked by their antics,” Bushman explains in the introduction. “We do read their literature with interest.”

For some of these writers, parenthood and the home is ample spiritual and personal nourishment: a veritable homily to motherhood—”Bless Sesame Street! That psychedelic learning feast!”—extolls its joys above all else. But not all found the life of a stay-at-home parents so straightforward. Another writer explores the challenges of balancing a frowned-upon writing career with being mother and stepmother to five boys. On occasions when an unexpected visitor appeared at the door, the writer notes, she felt obliged to hide her typewriter and assume her position by the ironing board.

The group behind this issue of the journal were emphatically not “against” men, Mormonism, or the value of a structured family unit, but a strong sense of questioning the status quo comes through nonetheless. Far from calling for mass abandonment of husbands or burning of bras, many of its writers advocate for women to have more choice and a less prescribed role. “In all honesty, we are not always completely satisfied with our lives as housewives,” Bushman wrote. And even among those who were, it seemed a shame that “women with strong career orientations” faced terrible pressure to marry, and disapproval if they pursued their “special interests” outside the home.

The church’s leadership, however, was moving in almost precisely the opposite direction. In 1978, recognizing some of these countercurrents, then-apostle Ezra Taft Benson spoke out about these “feelings of discontent” among young women who wanted more “exciting and self-fulfilling roles” than to be wives and mothers. Church policy, he argued, leaves little room for that: “This view loses sight of the eternal perspective that God elected women to the noble role of mother and that exaltation is eternal fatherhood and eternal motherhood.” Like Kimball before him, Benson was setting down scripture. That “eternal perspective” might not have always been so explicit—but it was now.

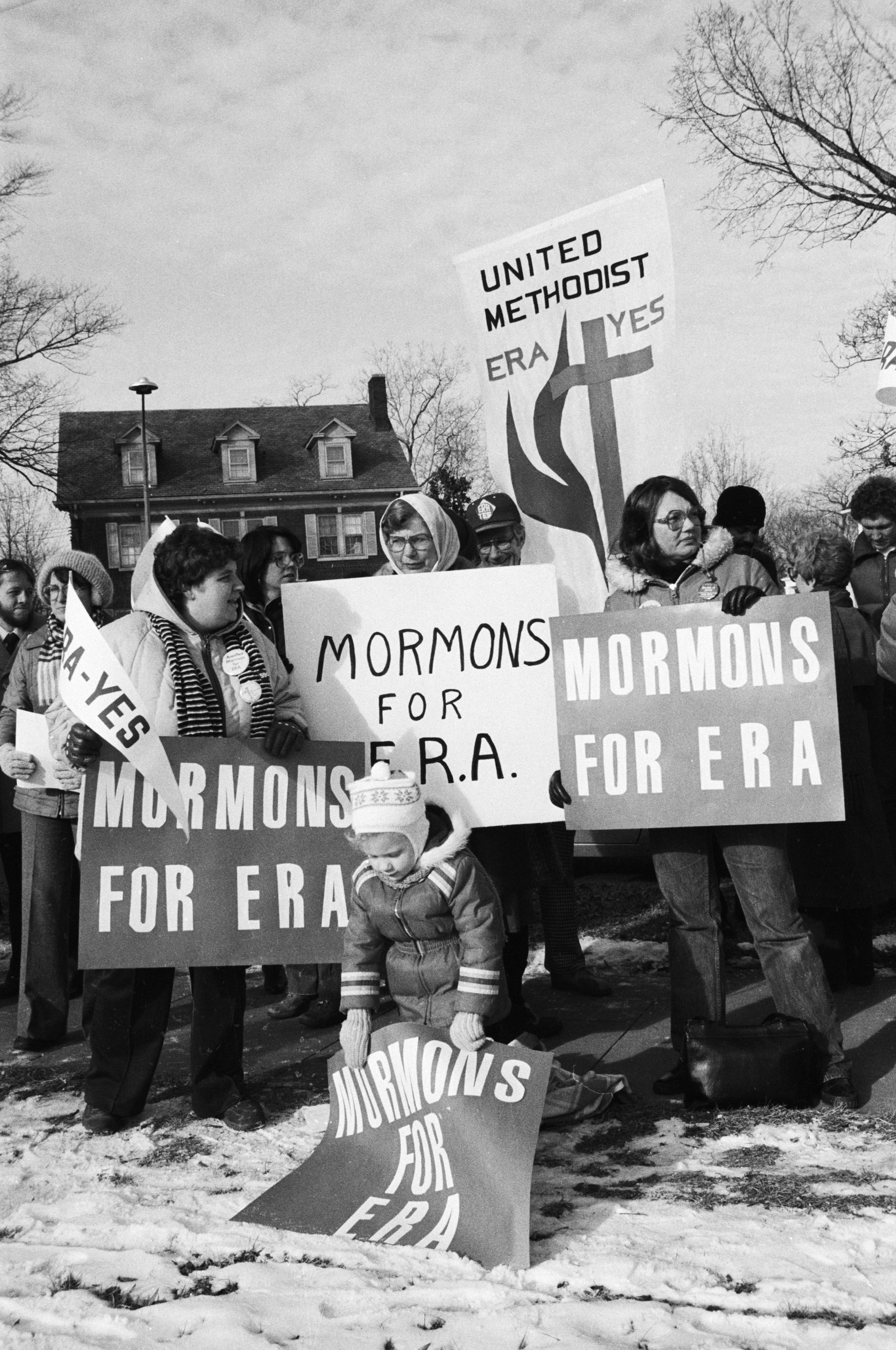

Ordinarily mostly apolitical, the church applied its clout in 1979 to wage an out-and-out war against the pro-gender equality Equal Rights Amendment, on the grounds that it did not recognize the “vital” differences “biologically, emotionally, and in other ways” between men and women, as one church elder put it. Sonia Johnson, an LDS woman who campaigned in favor of the Amendment, was summarily excommunicated on the grounds of “teaching false doctrine.”

In the decades since, the church has grown still more conservative in its stance on women’s roles. In 1987, Benson gave a sermon in which he encouraged women to quit their jobs. Then, in the early 1990s, six high-profile Mormon intellectuals, many of whom were outspoken LDS feminists, were excommunicated. Next, in 1995, the church published its official view on how family should be composed, noting the “divine design” of a one-income family. The following year, church president Gordon B. Hinckley reiterated the message at the annual General Conference, an annual gathering of members: “It is well-nigh impossible to be a full-time homemaker and a full-time employee.” (Only women, it was strongly implied, could be the former.)

Divine, domestic bliss?

Nearly two and a half decades later, many of the same arguments about managing work and domesticity are still being thrashed out. Though many LDS women find motherhood to be empowering and spiritually fulfilling, plenty of others struggle to live up to that Mormon ideal of divine, domestic bliss. Those who seek professional goals instead, or as well, often find themselves marginalized from the LDS community in the process. Kelly’s LSAT cohort at BYU had “maybe two women” in a class of over 50, she remembers; at law school, she discovered that only men were permitted to be leaders in the Mormon lawyers’ association, the J. Reuben Clark Law Society. At the association’s meetings, she was directed to “a separate room where all the wives were,” despite being a member in her own right. In her “most intimate community,” these professional choices were “very frowned upon,” especially by her then in-laws.

Online, LDS feminism has surged in popularity, with the internet providing a forum for hundreds of young LDS feminists to congregate, share links, or question commonly held assumptions about how Mormon women should behave or live their lives. Forums such as I’m a Mormon Feminist or Young Mormon Feminists have become places where women’s voices have primacy. Often, these explore the best way to be a liberal feminist and follow Mormon teaching. The group blog Feminist Mormon Housewives, for instance, is only very barely tongue-in-cheek, if at all. At the same time, a majority of LDS women still dismiss the feminist movement as irrelevant to their lives or even heretical—on Twitter, one young Mormon woman self-identifies as “not a feminist” in her bio, while another notes: “Anything that can convince women to kill their own babies and pursue something as fleeting as career over family can’t be of God.”

Despite this curiosity, church leadership shows no sign of updating its perspective from the one stated some decades ago. Suggestions that women enter the leadership, for instance, have been shot down vehemently—in 2013, Kelly and a group of LDS women started the organization Ordain Women, the foundation of which eventually led to her excommunication on charges of apostasy. But, in what might be read as a conciliatory spirit from the leadership, smaller challenges have been more successful. In late 2012, a group of Mormon feminists launched the first Wear Pants to Church Day; since then, female church employees and missionaries have had the right to sometimes wear dress slacks while working. In 2015, women first gained the right to serve on high-level church councils.

LDS women seeking to make ends meet tend to look for the gray area, working “inside the home,” by selling products on Etsy or monetizing being a blogger or influencer. Multi-level marketing schemes, in which people sell products to their friends or neighbors, are also hugely popular as a way to follow church policy while contributing financially. “There’s so much pressure in LDS culture to be a stay-at-home mom,” Mormon mother and Lipsense lipstick consultant Alyx Garner told the Utah CBS affiliate KUTV. Direct sales isn’t the most lucrative way to make a living—Garner might make $1,250 in a month—but it’s a compromise between her need to have an income and her desire to adhere to church policy.

Even as the church remains steadfast, Mormon households are still subject to larger economic forces. Throughout the US, only the very wealthiest families can easily get by on one salary. Now in her 80s, Bushman has spent the last decades of her life in academia, specializing in domestic women’s history. She encounters many women who would like to follow church policy, but simply can’t afford to. “It’s a miserable situation,” she told Quartz, “There’s very little support for at-home mothers, and families can now hardly get along with less than two incomes.”

It’s not hard to see how this failure to modernize places undue burden on women. If they don’t work, their families may struggle economically. And if they do, they face tremendous social pressure, or the implication that they are bad mothers. Women who rely on childcare, for instance, must tolerate the shame of literally going against the word of their religion, which considers motherhood a “divine service [that] may not be passed to others.” It’s a bind—and one that many women struggle to disentangle.

For the LDS leadership, the challenge is also tremendous. Having adopted such a cut-and-dry approach to women’s roles, it is hard to argue that God has changed His mind, or that earlier prophets were mistaken. But with more Mormon women continuing their education, marrying later, and embracing mission work, some leaders are making moves toward a more permissive approach. Speaking in 2011, church elder Quentin Cook praised stay-at-home mothers—but added that those sisters who worked outside the home were not necessarily any “less valiant.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints believe in the Holy Trinity. In fact, they believe in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost as separate entities.