Senior living is starting to look like millennial living

On the day we moved my mother into an assisted-living facility, the only reason I was able to tell her that she would see her home again was because I honestly believed it.

On the day we moved my mother into an assisted-living facility, the only reason I was able to tell her that she would see her home again was because I honestly believed it.

Over breakfast that morning, as she made her ritual tea in her own kitchen, she looked at the boxes and suitcases my sister and I had packed and repeatedly sought reassurance about our plans. “But I’ll be coming back eventually, right?” she asked.

“I hope so,” I told her, careful not to overpromise. “That’s the plan,” I said the next time she asked.

When we finally locked the door behind us, the house still looked like it was waiting for its occupants to return, with all the furniture and family photos in place, the beds made, the closets jammed as usual with coats and snow boots.

I still had so much to learn.

In the first story we published for this series, I explained that my father’s dementia had landed him in the hospital nearly two years ago, sending me and my sister on a grand tour of assisted-living homes in suburban Toronto, where my sister lives, and—because we weren’t sure what we were doing—near our parents’ rural village more than two hours away. (I live in New York, so that locale was automatically ruled out for them by virtue of citizenship.) What I didn’t mention was that my mother could not be my father’s caregiver because she has dementia too.

Whenever this comes up in conversation, I try to make the news less burdensome to the listener by adding that, compared to my father’s disease, my mother’s affliction has moved at a snail’s pace, and has been essentially limited to her short-term memory. With him, it was like a bomb went off in his brain. In the space of a year or so, he became increasingly emotional and paranoid. He saw people who weren’t there, and called the police on them in the middle of the night. He bought a $4,000 vacuum before realizing he’d been conned by a traveling salesman.

Then one day, after a night of agitation and hallucinations, he had a small seizure during an X-ray at a local hospital. Because I had accompanied him for the appointment, I was on hand to help a nurse rush him to the ER. And that was it. He didn’t die, but he never went home again. It took the coordinated efforts of a team of people—one particularly generous neighbor, extended family, and various community health nurses and social workers—but my sister and I moved both of our parents into an assisted-living facility after our father’s month-long, delirium-inducing hospital stay.

Even as it was finally happening, I resisted considering their relocation permanent. I worked the phones searching for a private caregiver who might move into my parents’ house if my dad’s behavior could be stabilized with medication, but the rock-bottom rate I sourced from a local agency was a minimum of $250 per day, assuming only one person in the home needed care. A freelance care worker quoted me $17,000 monthly.

If we’d had that kind of money, I would have spent it. Every night, my parents were packing up their belongings at their assisted-living center and calling us and other relatives to ask for a ride home.

But the option we had chosen for them had one saving grace: My mother, who had joined our inspections of different retirement homes, thought the properties were beautiful. She marveled at the grand pianos and found the idea of sitting down to be served three meals per day preposterously luxurious. “No more laundry?” she said, clasping her hands with glee. “Oooh,” she said, when we stepped into one residence’s small library and took note of the wingback club chairs and shelves lined with the latest bestsellers. “I’d love to live in a place like this,” she said.

Now, with the benefit of time, I can say that assisted living was the right call for our circumstances, which isn’t to say that the industry is perfect. Here’s what I’ve come to learn, as an indirect customer, about the fast-changing world of senior housing.

It’s unavoidably expensive, but so is staying home

The high cost of decent senior-living residences is the primary reason everyone should be preparing for their own future, as well as that of their aging parents.

In North American cities, the cost of rent in a modern assisted-living residence is typically around $4,000 to $5,000 per person, per month, which includes meals and light housekeeping. Rents are lower in second-tier cities and rural areas. Memory care packages can be an extra $1,000 or more, per month. Some upscale urban developments, featuring the modern aesthetics that the moneyed often prefer—think Room & Board instead of Raymour & Flanigan—will feature kitchens equipped with herb gardens, access to lap pools, and physiotherapy, along with exclusive outings to the theater or opera, though monthly per-person prices can reach $20,000 or more.

You wouldn’t know any of this by cruising the websites of all the businesses that will come out of the woodwork when you first google “seniors’ home near me.” Frustratingly, most senior housing websites do not include price sheets—your first sign that this industry has not yet been forced to take transparency as seriously as others selling big-ticket items, like colleges or regular real estate. To get your hands on some price tags in this market, you’re obliged to hand over your contact information at least; you’ll then likely receive a follow-up phone call, which might broach the topic of finances, and you will be invited on a tour.

Senior housing companies claim that the pricing is too complex and customer-specific to make sense for them to share it openly. That reticence may only be natural in a business that so many people purposefully ignore and thus don’t understand.

When you finally do learn the cost of care, without context, it seems scandalous. Then you add up the costs of in-home care, plus groceries, home insurance, electric and water bills, and the hassle of finding and paying someone to fix a leaky roof, shovel snow, and mow the lawn. You think about the pathetic “meals” your parents have been eating—plenty of seniors who age at home start eating things like Cheerios or oatmeal cookies, and little else all day—and the promise of a selection of warm, chef-prepared meals is a particularly meaningful benefit.

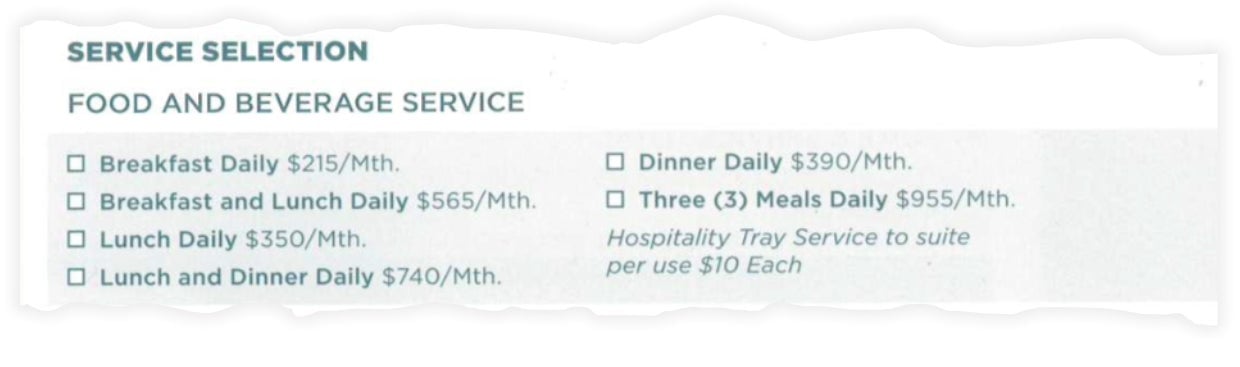

But then, just when you’re starting to wrap your head around the rent, you’re bound to discover that it doesn’t include add-ons and extra costs, including a one-time move-in fee, or tiered pricing for medication distribution. At one property, we found that if Dad takes five pills, med management would cost $22 per day, but six would bump him into the next price range, at $28 per day, or more than $800 per month. Extra housekeeping may cost $25 per 15-minute interval. An extra shower? At one spot, that was $14.

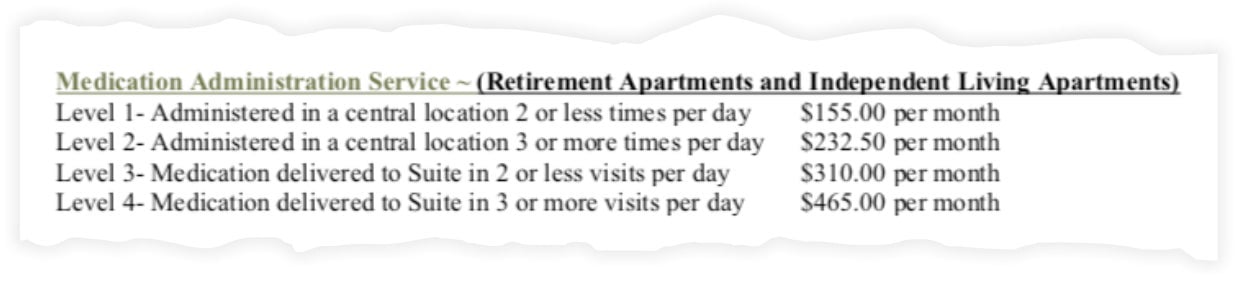

Whether or not medication is brought to your room can also impact fees:

With time and its ravages on the body also comes costs for more intense care, too, meaning your invoices can jump up a few thousand dollars per month. Most seniors who move into senior housing have some limiting condition, like heart disease, chronic pain, or memory loss, that makes complete independence impossible or hazardous. A fall can lead to a broken hip, a fainting spell can cause a head injury. Loneliness is itself a powerful risk factor for cognitive, emotional, and physical decline. What is an appropriate price for any extra care required? Meanwhile, it’s not entirely clear that higher prices mean better care, or more staff, as a Florida lawsuit alleged in 2017.

The most ethical salespeople will make the potential for higher monthly bills clear at the outset. They might claim the home, like an airline or hotel, keeps costs down for those consumers who need less. But there are signs that unbundled pricing has been played out: At the showroom for the still-under-construction Sunrise at East 56th Street, a luxury Manhattan assisted-living facility, a sales manager told me that the property has done away with piecemeal add-ons—customers find them grating.

Similarly, Elroy Jespersen, founder of The Village Langley, a dementia village in British Columbia (the first of its kind in Canada), may be onto something with his simple arrangement: Assisted living is $7,300 per month and complex care (equivalent to nursing home care) is $1,000 per month more.

Senior living and millennial living are starting to look alike

My parents are now settled in an assisted-living home run by a large Canadian chain. It suited our budget and gave my mother access to an upright piano on the memory care floor and a commercial grade Nespresso machine that dispenses sugary mochas and foamless cappuccinos, for free, in the basement bistro. On the same level, just across the hall, the billiards room is inviting enough—with its dark taupe walls, gold accented furniture, and old photos of local skating clubs— that my father will stop pacing long enough to play a rules-agnostic game of pool.

As I’ve spent time visiting them there, I’ve come to see how much these places have in common with other co-living spaces that don’t have such a bad rap. As you would in a college dorm situation, in a senior living home, you furnish your own room and sign up for a meal plan—or not, if you’re in independent living (see our glossary for more on these distinctions). The bulletin boards feature invitations to expert talks on wellness or history, along with fliers promoting luncheons, and announcements about special vendors with crafts for sale who will be visiting the building, as they might in a WeWork.

Senior communities have been known to make field trips to marijuana dispensaries and invite food trucks onto the property, according to Senior Housing News, and one in Atlantic Beach, Florida built its own.

Assisted living also, rather famously, has its own version of hookup culture, only here it’s enabled by the dark cover of movie night and a tendency to live with less inhibition in old age. More than one salesperson I met made a winking reference to this phenomenon, even though they knew my parents were arriving as a couple. The subtext of every hosted tour is “life goes on.”

The more upmarket you go, the more the aesthetics of millennial and senior living blur. At the Sunrise at East 56th Street showroom in New York, the look is contemporary and urban. (Increasingly, retirees want to live in walkable areas, rather than an old-age island on the edges of town.) I spied Kind bars stacked by an espresso machine in a model of a kiosk that will be found on every level of the 17-floor residence when it opens next year (the entry cost is $13,000 per month for a studio). I immediately thought about millennials casting about for precisely the same snacks and caffeine in startup spaces all over New York City.

Let’s not forget that millennials have become homebodies, making them not very different from 70- and 80-somethings who stay in most evenings, many connecting to loved ones through screens, whether via FaceTime or an Alexa-enabled device—which, by the way, are arriving pre-loaded in some new seniors’ units and are getting installed in others.

Millennials call Ubers and Lyfts to take them out when they do leave their homes; a small but growing number of seniors do, too, because paratransit, which needs to be booked 24 hours ahead of time, is far less convenient and still carries a stigma, says Stephen Golant, a gerontologist and geographer, and professor emeritus at the University of Florida.

Millennials also would feel at home in the Sunday brunches at my parents’ retirement home, where only the occasional phlegm-y hacking of old men and the clutter of walkers betray your venue. There are cliques of friends getting together, gossiping and trading opinions about politics or the quality of the french toast versus the omelettes.

Yet there’s one big, unavoidable difference between millennial co-living or co-working communities and senior housing: in the latter, when your friends stop renewing their memberships, it’s never to take a new job in Atlanta or to spend a few months touring Southeast Asia while working remotely.

The constant losses can take a toll. I know of a widower in Toronto, a friend’s father, who moved into an upmarket assisted-living place when he lost his wife. The new environment eased his loneliness at first, until he noticed a pattern: He’d make a new acquaintance and the next week discover that the friend had been taken to the hospital, and wouldn’t return.

That’s what assisted-living boosters rarely emphasize: These are the places you go to at the end, or the beginning of the end, of your life. Your spiritual or creative life may deepen if that’s your bent—plenty of the facilities offer yoga and craft rooms, and some niche senior co-living spaces target artists specifically—but physically, the most you can usually hope for is a long plateau.

Insiders say this is one of the problems that next-generation senior housing is likely to fix: it will stop creating elder ghettos in favor of multi-generational projects, and encourage relationships across generations through shared spaces and experiences, like college classes, gyms, or mentoring programs.

There are, however, issues with assisted living that are far harder to solve and that do not mix well with the social-justice agenda that has become a millennial hallmark.

The social injustices outside assisted living persist on the inside

In the US, there is currently a labor shortage for every category of employee in assisted living—from facility directors down to the care assistants. It exists partly because of low unemployment in the labor market generally, but also thanks to fears about current and future immigration policies (estimates say nearly a quarter of direct care workers across various settings are not born in the US), and increased competition as more developers break ground on new senior-housing projects.

Industry and academic sources project a need for 1 million to 2.5 million additional long-term care workers over the next decade, according to the nonprofit National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care. (The home-healthcare business is confronting the same labor crunch, only on an even more massive scale.)

But the laws of supply and demand don’t seem to be working properly when it comes to salaries for the industry’s lowest-ranking workers. The people who help your mother shower, or who are present when a dementia patient throws a violent tantrum, or who laugh it off when your cranky father compares the texture of his steak to the backside of a hound, are, in many cases, struggling to get by and often relying on public assistance for their own housing and groceries, according to data from PHI, a Bronx, New York-based research and advocacy group for direct care workers.

PHI’s most recent data, from 2018, shows that the average hourly wage for this class of caregivers (including those in residential facilities for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities, as well as senior-living centers) is $12.07 an hour, landing between the median wage for home care, which is $11.52, and the $13.38 median wage for nursing assistants and nursing homes. That puts their median annual earnings at $20,200. “For a lot of workers, this is a poverty-level job,” says Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI.

That problem is only compounded by all the consolidation in the industry, with fewer profit takers controlling the fortunes of a greater number of caregivers.

One reason the work pays so little is because, in the US, the single largest payer of caregiver salaries is Medicaid, and the wages set by nursing homes anchor the salary levels for caregivers in the private-pay setting. But another influential factor is the historical legacy of this type of work, says Scales, “which is being seen as low-skilled work, sort of naturalized feminized labor.” The industry and our culture are only now “catching up with recognizing how important this work is, what skills it really does take to do it well, and how important it is to our long-term care system, our communities as a whole, and our economy,” she adds.

Josh Crisp, a senior living developer and marketer in Tennessee and co-host of Bridge the Gap, a podcast about the industry, tells Quartz that a reckoning is most likely coming, as senior housing companies look for ways to pay people more, without necessarily passing the cost onto residents.

“I do think if we are going to become an industry with more-affordable options—I’m conscious to not say [just] affordable, because affordable is a very relative term—everyone’s margins are going to suffer. You know, my margins as a manager/operator are going to suffer—the capital markets, investors, their margins are going to have to suffer.”

Let’s not forget that who gets to be a resident at these facilities also is symptomatic of larger inequalities in our culture and economy. Because the assets you acquire in life, including the house you might sell to pay for assisted living, are often dictated by race and class, the option to choose this style of living belongs to the privileged, while not enough people are working on solutions for low-income seniors. To make senior housing more palpable to the next generation of customers, something will have to give.

Happiness is never a given

You won’t find a lot of reviews of senior living properties on sites like Yelp or Facebook, though Tim Mullaney, editor in chief of Senior Housing News, says smart providers are starting to pay attention to what’s happening on social media. That part of millennial culture is coming to disrupt the broker-driven referral system that has dominated so far.

For now, the best barometer of how happy you or your parents might be with a particular assisted-living home is your knowledge of who they are already.

I can’t say my parents have found bliss in their new living conditions. Rather, they have had many moments of contentment and joy that punctuate days of boredom. But it also turns out that you can’t always go by what you see. One manager at a home my parents tried out observed that I was pleasantly surprised to see my father waltzing merrily with a caregiver one day. “Family members don’t see the full picture,” I remember the manager saying. “They get a tearful call and they feel terrible, but they don’t know that half an hour later, their parents are all smiles in Zumba class.”

I’ve come to the conclusion that there’s only so much control you can have over the happiness metric. As a family member, you do your homework, choose wisely, and advocate as needed, but ultimately, people are who they are. Their life experiences, genetic make-up, and cultural expectations may all combine to make them a curious soul who makes friends easily—or they might struggle to adapt.

This was never clearer to me than the day I watched the seniors at a mid-summer dance party at my parents’ residence. My mom and dad were still the new kids, hanging back nervously, and most of the other seniors clapped along politely. But one woman barely sat down. With every danceable tune, she took to the floor, waving her scarf as she danced, almost Bollywood-style, to Elvis and The Beach Boys, without a partner. The man I recognized as her 40something-looking son came rushing in, perhaps as soon as he could make it there from work, but he didn’t try to get her attention. I saw him smile at his mother admiringly as he watched her for a few minutes, until he could slip away unnoticed, and return, I presume, to his own life. For the children of assisted-living residents, in families that can afford it, this is peace of mind worth paying for.