Dodgy dealings in China’s steel trade puts some big banks at risk

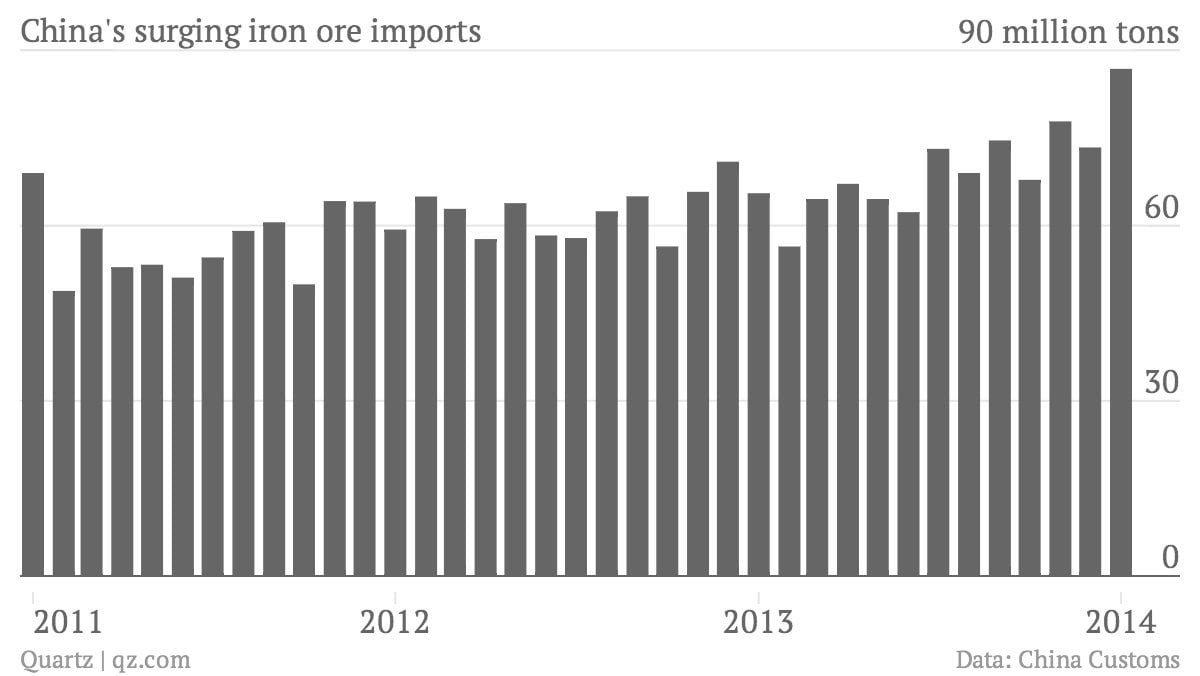

China’s iron ore imports are through the roof: the record-high 86.8 million tonnes (96 million tons) of foreign iron ore China bought in January was a 32% increase on the previous year. What’s weird is that the ore didn’t actually go anywhere. Around 100 million tonnes are still sitting at various ports around the world—the first time since July, 2012 that port inventory has been that high.

China’s iron ore imports are through the roof: the record-high 86.8 million tonnes (96 million tons) of foreign iron ore China bought in January was a 32% increase on the previous year. What’s weird is that the ore didn’t actually go anywhere. Around 100 million tonnes are still sitting at various ports around the world—the first time since July, 2012 that port inventory has been that high.

Steel stockpiles are up too, which makes sense considering China’s slowing economy and steel-sector overcapacity. But why, then, is anyone buying all that iron ore?

Not to build. To borrow.

For years, traders have use iron ore and steel inventory as collateral for loans, often pledging the same pile of iron ore or steel to take out multiple loans from different banks. They would then make a killing lending out those proceeds via shadow credit channels that make up China’s $6 trillion off-balance-sheet banking system. Traders often mutually guarantee (link in Chinese) credit applications, creating a scarily Ponzi-like structure.

The steel sector is so deeply immersed in shadow finance that state news agency Xinhua recently reported that at least one-third (link in Chinese) of the country’s 200,000 steel trading shops would be wiped out in the event of a liquidity crisis.

But as the price of steel has plummeted, it looks like that trade may be starting to unravel. Steel-related lawsuits in Shanghai, China’s steel trade hub, are up (link in Chinese), as are reports of steel-trading bosses skipping town or leaping out of windows (link in Chinese). Last week, a loan dispute with Minsheng Bank prompted a Shanghai court to freeze the assets of an investment vehicle controlled by a man known widely as the “Steel-Trading King,” who also happens to chair Shanghai’s steel exchange. In January, the People’s Bank of China launched an investigation into credit card fraud among steel traders, who had reportedly been drawing funds far in excess of their credit limits to cover debts.

This is, of course, ultimately bad news for Chinese banks and the broader economy. In the southern city of Foshan alone, local banks have given 100 billion yuan ($16.5 billion) worth of credit (link in Chinese) to steel traders. Loans to the sector helped drive non-performing loans in Yunnan province to nearly 6% as of Nov. 2013, reports Caijing (link in Chinese).

“There are a lot of bad loans that are unrecoverable, even through litigation,” a bank staffer familiar with the steel trade industry told Caijing. “The only way to manage them is to write down the losses. This bloodbath of a lesson will definitely force banks to reevaluate risk.”

Another worry in all this is that this will hit global prices; Chinese demand accounts for nearly two-thirds of the world’s seaborne iron ore trade.