How YouTube shields advertisers (not viewers) from harmful videos

The difference between the protections YouTube offers its advertisers and those it provides consumers is stark. A read of advertiser-friendly content guidelines for videos uploaded to the platform, last updated in June 2019, shows the company has rigorous standards to protect advertisers from harmful content and the algorithmic ability to do so. Yet YouTube does not consistently flag these same videos as problematic to viewers, despite ongoing criticism that the platform allows conspiracy theories, the alt-right, and extremism to flourish.

The difference between the protections YouTube offers its advertisers and those it provides consumers is stark. A read of advertiser-friendly content guidelines for videos uploaded to the platform, last updated in June 2019, shows the company has rigorous standards to protect advertisers from harmful content and the algorithmic ability to do so. Yet YouTube does not consistently flag these same videos as problematic to viewers, despite ongoing criticism that the platform allows conspiracy theories, the alt-right, and extremism to flourish.

“I’m extremely disturbed,” Nandini Jammi, co-founder of Sleeping Giants, which campaigns to stop companies advertising on unethical websites. “They have multiple standards. It’s like they’re two-timing their users. Content not safe for brands is likely not safe for users either.”

Historically, in both print and digital publishing, advertisers have chosen content along with which they don’t want to appear. YouTube goes a step further, informing all content partners that certain videos are deemed unsuitable for ads. This means that advertisers needn’t worry about appearing in connection with such videos.

Hate speech for advertisers versus the community

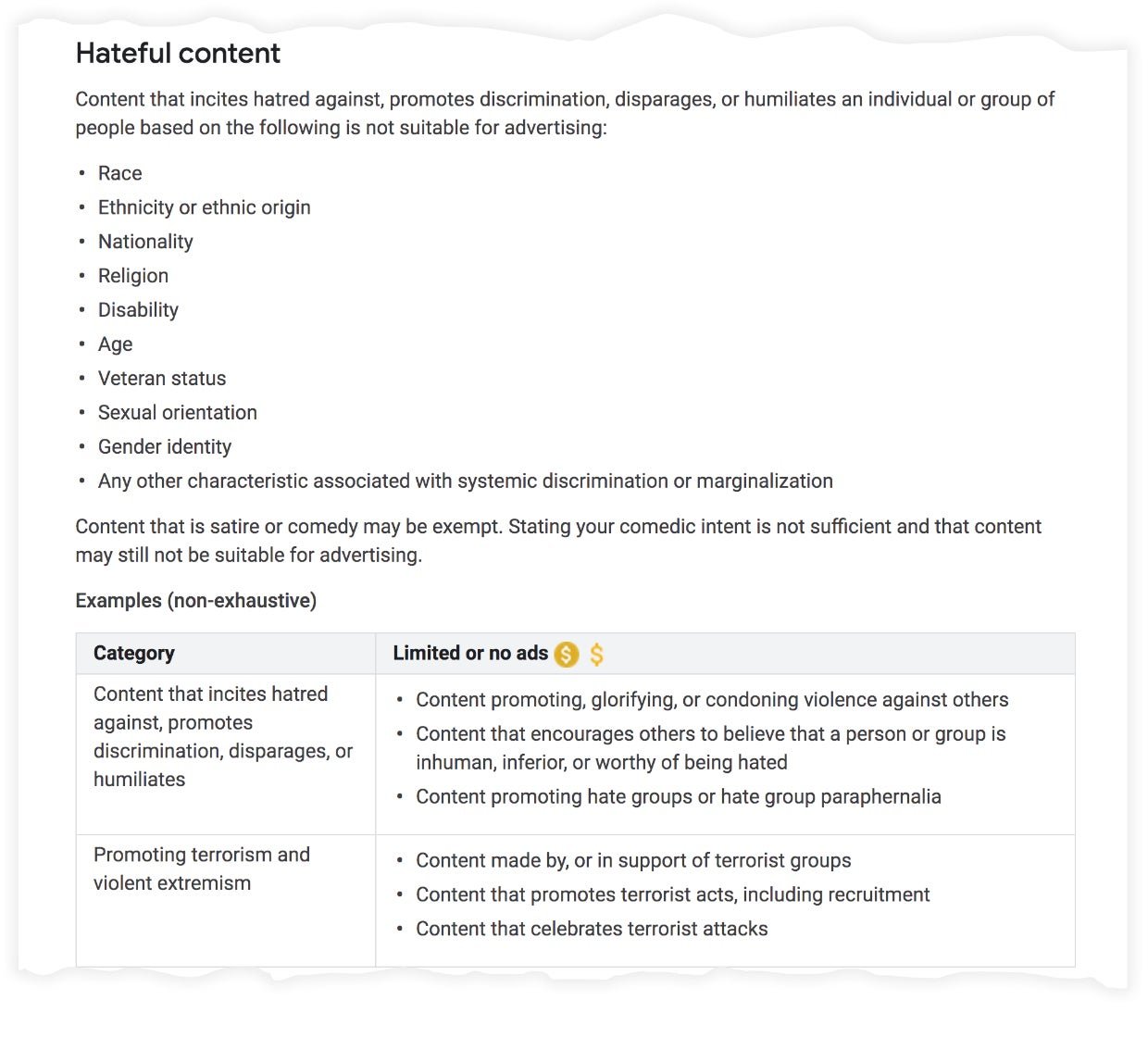

YouTube provides video-makers and -uploaders a non-exhaustive list of topics that aren’t considered “advertiser friendly,” including hateful content, incendiary and demeaning videos, violence, and harmful or dangerous acts. For example, the list of “harmful content” includes:

When it comes to prohibiting hate speech on YouTube in general, the company has a looser set of community guidelines, with a slightly narrower definition of hate speech than in advertising guidelines. For example, while the community guidelines prohibit explicit statements that groups are “physically or mentally inferior” or “subhuman”, the advertiser-friendly guidance is broader, saying ads will be restricted next to “content that encourages others to believe that a person or group is inhuman, inferior, or worthy of being hated.” The advertising guidelines also say ads will be limited or won’t appear next to content promoting hate groups, whereas the community guidelines only prohibit videos that explicitly contain “hateful supremacist propaganda.”

In practice, community guidelines are often less strictly enforced*; YouTube has a “bias toward free expression as far as what we allow on YouTube,” spokesperson Alex Joseph wrote in an email to Quartz. The gap in guidelines plays out by allowing videos that seem to encourage discrimination permitted on the platform, only without ads. Channels run by alt-right figures including Steven Crowder, Nick Fuentes, and Stefan Molyneux have been deemed unsuitable for ads even as they’ve racked up huge followings.

A gap in policies for harmful health information

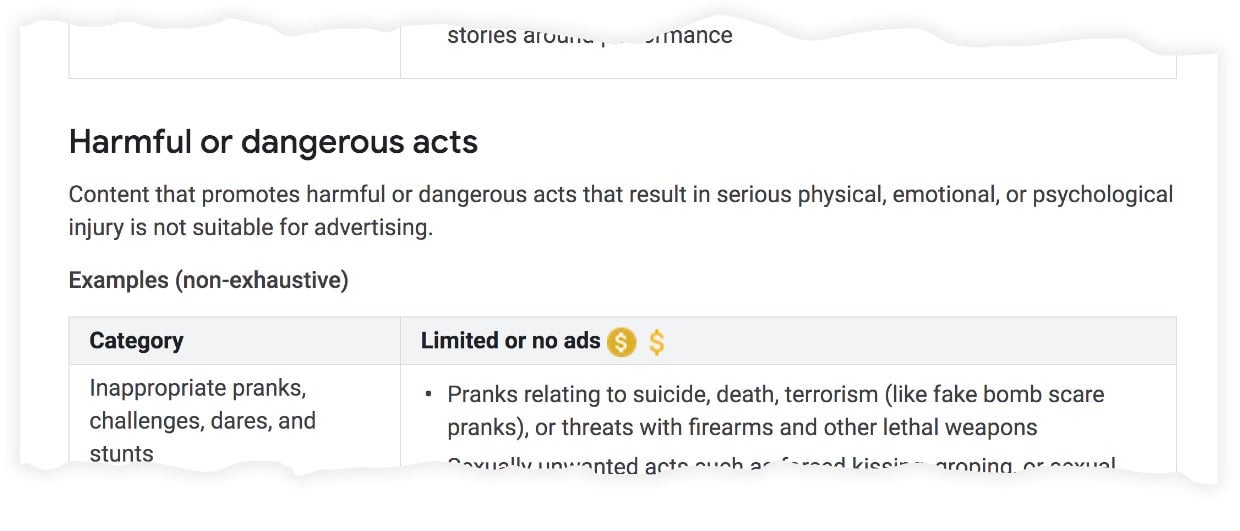

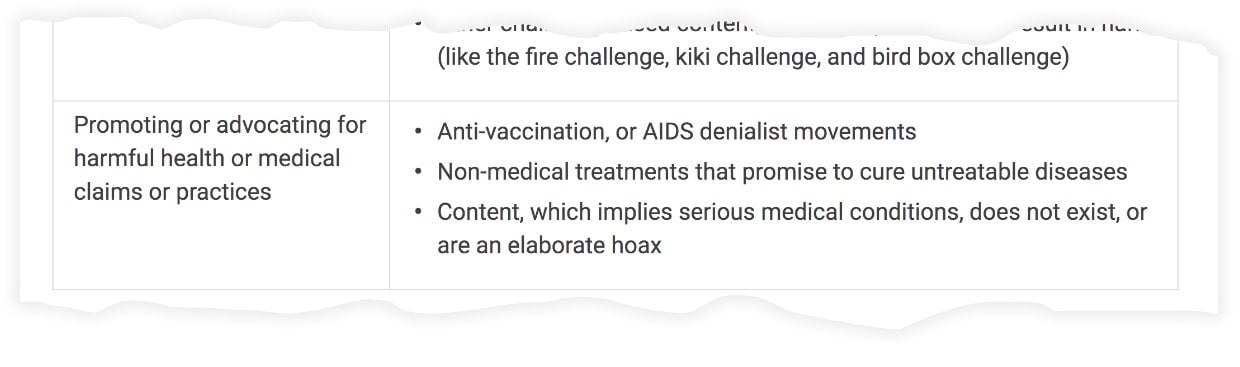

A similar difference in advertising versus community guidelines is evident in YouTube’s policies on misleading health information. Their advertising-friendly guidelines read, in part:

The advertising guidelines say YouTube will restrict ads next to videos promoting “harmful health or medical claims or practices.” This includes “non-medical treatments that promise to cure untreatable diseases” and content that implies serious medical conditions don’t exist or are hoaxes. Meanwhile, the community guidelines are more narrowly focused on “promoting dangerous remedies or cures: Content which claims that harmful substances or treatments can have health benefits.” In focusing on actively harmful substances, rather than non-medical treatments more broadly, the community guidelines leave out much of what’s addressed in the advertising guidelines.

These two separate policies seemingly allow videos that include harmful health information to exist, un-monetized, on YouTube. The company has been criticized for allowing videos with dangerously false health information to flourish, including those that claim insecticides or malevolent corporations are behind the Zika virus, and that vegan eating can cure cancer. (All three of these videos have tens to hundreds of thousands of views, yet none have ads.) Joseph said the vegan smoothie video does not violate community guidelines because two years after the video was posted, the creator added a disclaimer stating that the woman in the video died from cancer.

In some cases, YouTube’s advertiser-friendly policy and community guidelines overlap; for example, Joseph notes that videos promoting violent extremism are banned from both YouTube ads and the platform as a whole. In other cases, the difference clearly benefits YouTube users; “News footage of sensitive events, sexual education videos with realistic depictions of genitalia, or discussion of controversial issues like sexual abuse, are permitted of YouTube but are not advertiser-friendly,” Joseph wrote in an email to Quartz.

What gets a warning?

No system of identifying harmful videos can be perfect, and YouTube has been criticized previously for allowing ads to run alongside videos promoting hate and terror. Jonas Kaiser, researcher at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, notes that YouTube faces questions of censorship and freedom of speech when it comes to what videos are permitted on the platform. “The relationship YouTube has with advertisers is more straightforward,” he says, adding that YouTube protects itself from suffering financially by working to remove ads from harmful content.

But YouTube does have the option of adding warnings to videos instead of outright banning them. None of the videos referenced above showing misleading information on Zika and cancer, or the alt-right channels created by Crowder, Fuentes, and Molyneux carry a warning.

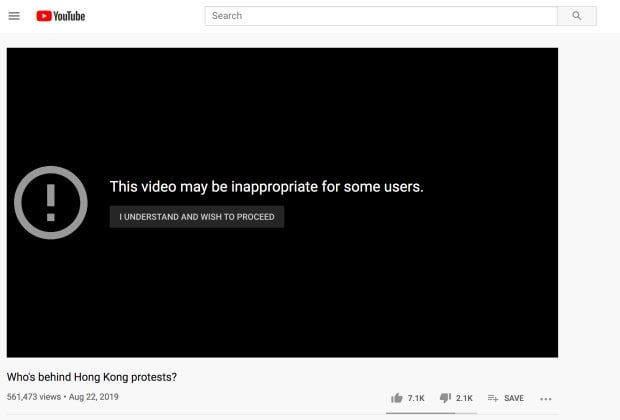

YouTube policy states videos should be marked inappropriate if they fall under “age-restricted content.” Promoting “harmful substances or treatments” and inciting violence are among the topics YouTube says it considers when age-restricting content. When YouTube does implement an age-restrictive warning—such as on a video created by China’s state media Quartz reported about in October—users are told “this video may be inappropriate for some users” and must sign in to confirm their age before watching. (YouTube marked this video as inappropriate for young people because it shows violent imagery, rather than because it’s state propaganda.)

YouTube has repeatedly claimed to be getting better at preventing the spread of harmful videos. In June 2019, the company said it was reducing recommendations for disinformation and videos on the borderline of what constitutes “harmful content.” At the time, Google chief executive Sundar Pichai said YouTube wasn’t “quite where we want to be” but the company was making progress at promoting authoritative videos. “We’re working hard. It’s a hard computer science problem. It’s also a hard societal problem. We need better frameworks around what is hate speech, what’s not, and how we as a company make those decisions at scale and get it right without making mistakes,” he told Axios. YouTube increased efforts to remove “hateful” videos after their June 2019 announcement, deleting 100,000 in the third quarter of 2019, five times as many as in the previous quarter. But harmful videos, spreading prejudice and misinformation, are still a major problem for the platform.

In a December 2019 statement, YouTube again said it was making “great progress” on attempts to “reduce the spread of borderline content and harmful misinformation.” One new initiative includes information panels on topics prone to misinformation. “For example, when people watch videos that encourage viewers to skip the MMR vaccine, we show information panels to provide more basic scientific context, linking to third-party sources,” reads the blog post. None of the above videos carry such information panels, though YouTube’s December statement says it plans to expand the panels to more topics and countries.

Jammi, from Sleeping Giants, says YouTube’s different policies for advertisers versus viewers suggest that the company is perfectly able to add more warnings to harmful content, but chooses not to. “By keeping this content alive on YouTube and pushing it on users, they can continue to maximize for their core metric, which is engagement,” she says. “As customers of YouTube, advertisers have the leverage and right to demand that their ads are placed on brand-safe content. As users, we don’t have that same leverage. We don’t have the same right to ask that YouTube protect us.”

*Update (Jan 22, 2020): YouTube disputes this. “We enforce both our advertiser-friendly guidelines and our community guidelines rigorously,” Jones wrote in an email following publication.