Hong Kong’s Lunar New Year pop-ups defy the government with protest-themed goods

From Molotov-cocktail-embroidered tote bags to “Be Water” chapstick, Lunar New Year shopping in Hong Kong has a distinctly rebellious agenda this year.

From Molotov-cocktail-embroidered tote bags to “Be Water” chapstick, Lunar New Year shopping in Hong Kong has a distinctly rebellious agenda this year.

All over the city, pop-up shops and not entirely legal street markets have cropped up in the days ahead of the new year, which begins on Jan. 25 and will be the year of the rat in the traditional Chinese zodiac. The sellers and shoppers are defying the Hong Kong government, which has banned stalls selling political-themed goods and satirical gifts—traditionally a mainstay of these markets—from its official new year bazaars. They’re also promoting what the protest movement calls “the yellow economic circle,” or spending in ways that support one’s political values. The tactic seems to be working—photos from the past weekend showed very sparse attendance at one of the main official markets.

Many of the defiantly unofficial markets, on the other hand, were hugely popular. One such market in Hong Kong’s Sai Ying Pun area was packed over the weekend, as shoppers came to spend at street stalls that in some cases will donate proceeds to the protest movement, and to buy locally made goods. It’s another reshaping of the economic landscape, with consumption shifting away from Hong Kong’s ubiquitous shopping malls which are now themselves frequently the site of protests.

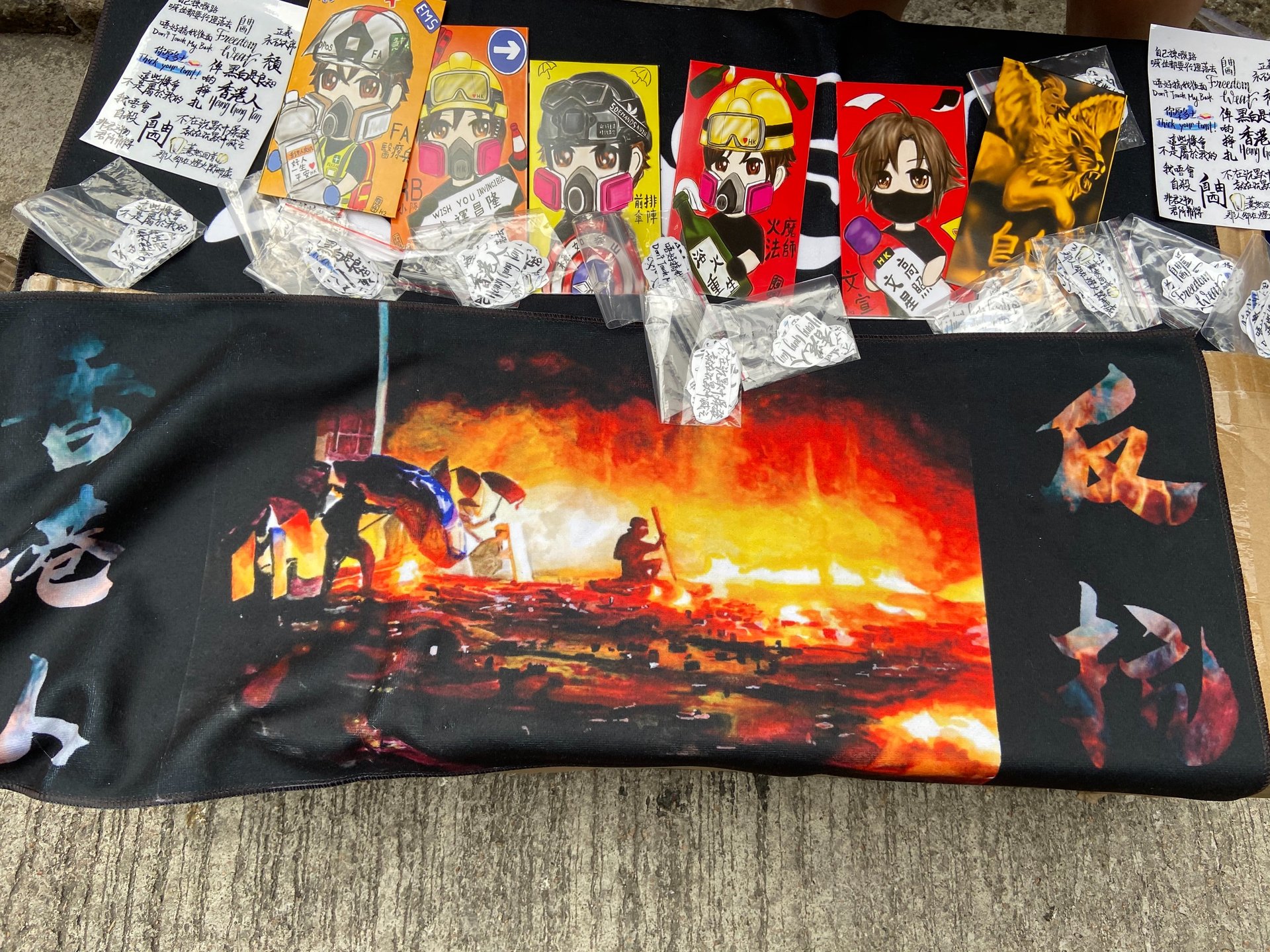

Many shoppers took photos at a stall in front of a massive print of a painting by an artist couple who go by Lumli and Lumlong. In the painting, the left side of the figure was a nod to the protests’ frontline fighters, and had been done by Lumlong, while the right side depicted the peaceful protester and was painted by Lumli. Among the weapons the figure is wielding are a traffic cone, water, and a pet food dish—all to put out tear gas, Lumli said.

“This year is very special,” said Lumli. “The government did not want to give the pass to us, so we have to make this market by ourselves… we want to develop our yellow market, our yellow economic circle.”

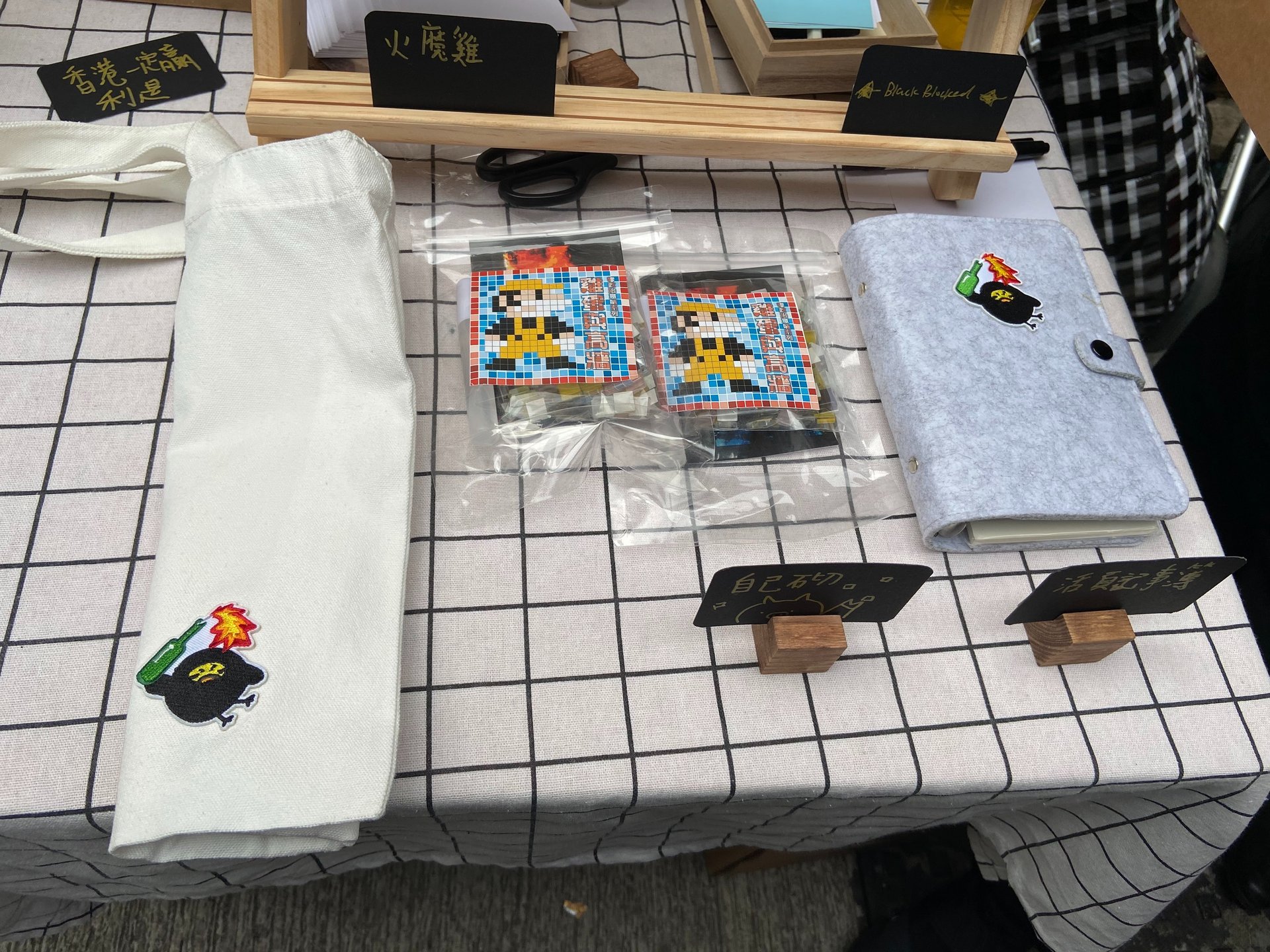

On the opposite side of the street, another stall was offering tote bags and a planner emblazoned with a petrol bomb patch. A young woman at the stall said the bags have been quite popular, and that they had sold about 100 of them. Since stalls at the market weren’t accepting payment directly, this involved sellers handing out chits and buyers going elsewhere to make a payment, in a line that at times included over 100 people waiting patiently to pay.

Next to them, high school students manned a stall with gift envelopes for giving out money during the new year. Each envelope depicted a kind of protester, or a first-aid volunteer. One envelope depicted an imaginary creature—a winged lion—that has become a common way to refer to vigilante justice, used at times by both protesters and their opponents. Nearby, “Be Water” lip balm was also on offer, a reference to the guiding philosophy of the protests.

One woman was selling patches which could be fixed to a purse, or sown onto a tee shirt. They depicted protest icons like Pepe the Frog, and a pig from popular local forum LIHKG known commonly as “LinPig.”

One of the most popular services at the fair was entirely free. As many as 50 people lined up at a time to get their bag or tee shirts hand-stamped with a logo that depicted a helmet and goggles, and a slogan.

A few train stops away, in the busy shopping district of Causeway Bay, another Lunar New Year market had set up shop in a pop-up space formerly occupied by a large cosmetics store. Hong Kong’s retail sales, driven by luxury brands, had a tough year in 2019.

In the pop-up store, people weaved their way through narrow aisles lined with various stalls, where different sellers plied their wares on tabletops. The atmosphere was so festive and relaxed—a far cry from the tense protests also going on that day—that when the lights temporarily cut out, no one seemed particularly annoyed. A miniature Lady Liberty—the statue depicting a protester in a gas mask, goggles, and a helmet—even appeared to glow in the dark. When the lights flicked back on minutes later, shoppers clapped and cheered.

One stall sold surgical masks explicitly marked “Made in Taiwan”—a nod to some protesters’ efforts to boycott China-related businesses. Another sold protest-branded wrist watches, with the hand mannequin holding up a miniature yellow umbrella. Close by, a stall selling flowers had decorated chrysanthemums into LinPigs.

With snacks often being a main attraction at these fairs, there was a wide selection of protest-themed foods. There were cookies decorated with LinPig and protest slogans, while one local brewery sold bottles of black IPA wrapped in the iconic blue-and-white checkered pattern of Life Bread, popular local brand of sliced bread. The humble pantry item became a protest symbol after video emerged in November of a police officer taunting protesters holed up inside Polytechnic University during the siege of the school, saying he would go enjoy sumptuous hotpot at the end of his shift while the protesters would have to subsist on sliced bread.

Yan, 23, a social work student who checked out one of the pop-ups on Sunday, said that she liked that most of the products were handmade and that she could support people with the same political stance as her. By buying something from these sellers—in her case a tote and a set of straws—she said she hoped she could also give a message to the government that “we are standing together to fight.”