Russian trolls and bots are successful because we know they exist

Everyone on Twitter is accusing each other of being a paid troll or bot. Some say the hashtag #AdamSchiffROCKS was made viral by bots paid for by conservatives’ favorite bogeyman George Soros. Others accused of actually being foreign puppets: supporters of Democrat Bernie Sanders, Republican senator Marsha Blackburn, anyone who makes spelling or grammatical errors, or simply those on the other side of any argument.

Everyone on Twitter is accusing each other of being a paid troll or bot. Some say the hashtag #AdamSchiffROCKS was made viral by bots paid for by conservatives’ favorite bogeyman George Soros. Others accused of actually being foreign puppets: supporters of Democrat Bernie Sanders, Republican senator Marsha Blackburn, anyone who makes spelling or grammatical errors, or simply those on the other side of any argument.

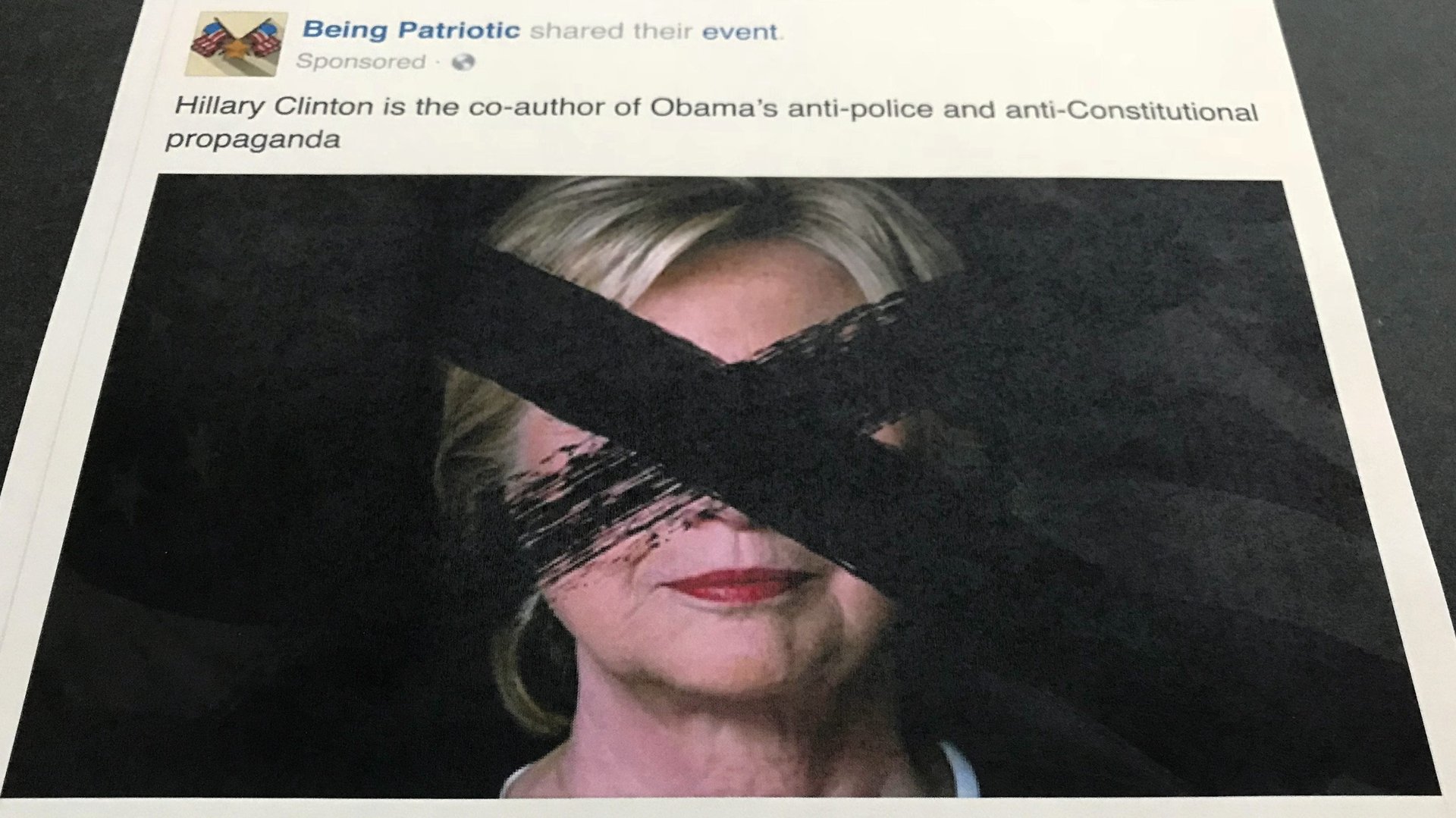

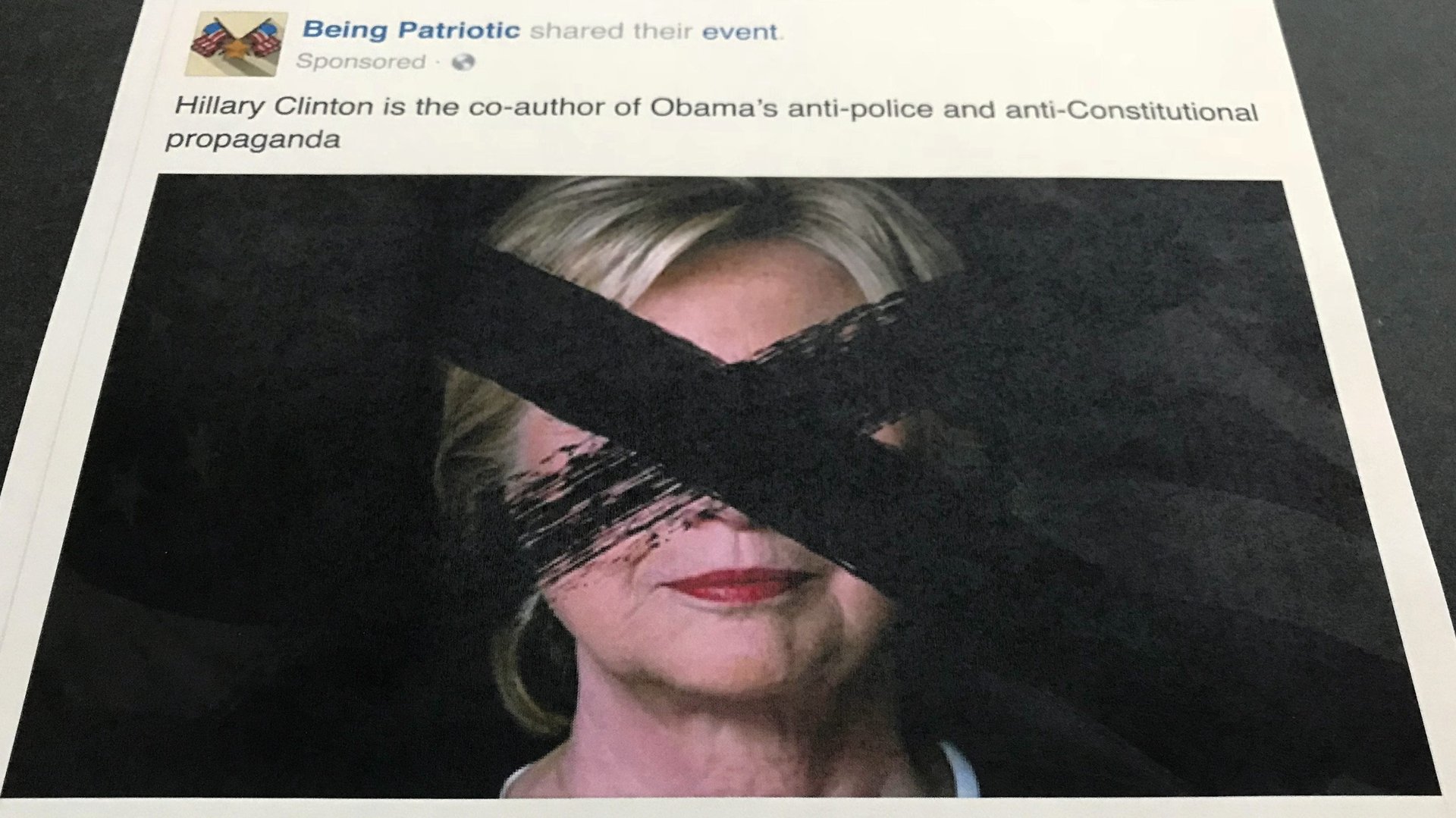

The real Russian (and other) trolls and bots are out there, perfecting their craft and using more sophisticated methods of obscuring their real identities than they did in the 2016 election, according to researchers. But it’s almost like they don’t need to do anything to achieve their goal of sowing chaos and discord: ordinary internet users will do the job for them. In 2016, most people didn’t know that Russian agents were trying to influence the US election by sowing discord and heating up emotions. In 2020, it’s because most people know that the trolls and bots are out there that bad actors can achieve their goal of chaos and acrimony, without doing much at all.

“There is a real danger of pointing fingers and making these accusations absent hard evidence,” said Emerson Brooking, a researcher at the Digital Forensic Research Lab of the Atlantic Council. “When we do have more evidence of the actual Russian operations the effect of that news will be minimized as we go making these accusations the entire election cycle.”

A “politicization of disinformation” threatens the study of disinformation, Brooking said. The landscape becomes “so confused and polluted that the clarity of the real threats is lost.”

It’s easy to make such an accusation that a social media user is a fake without any real proof—and those kinds of denunciations tend to get a lot of clicks. But actual, verified attribution is very tough even for experts in the field, Brooking said. For example, his research has shown that the behavior of older Facebook users is “essentially identical” to online sock puppets steered from abroad.

If you see suspicious activity online, you shouldn’t necessarily take it seriously. “You shouldn’t let it inform your political decisions, but that also doesn’t mean it’s a state operation,” Brooking said. You shouldn’t assume that “anyone who has a weird username is a Russian agent.”

Also, there is no need to look as far as Russia. There are plenty of domestic actors who are able to use the same methods, like networks of bots. Late last year, Facebook took down hundreds of pro-Trump accounts linked to a US-based publication.

“Those sorts of techniques should be called out,” Brooking said. “We just have to have certainty before we do so.”

There’s not much the average user can do, Brooking added in an email.

“These false attributions and accusations spring from people with large platforms who have found that labeling someone a bot or a Russian troll is a great way to build an audience. The best way to address this problem is to have an established research community that can independently assess these claims and push back as needed. This is only beginning to happen in the field of disinformation studies.”