Space companies are scrambling to solve the problem of defunct satellites

Two long-defunct US satellites came within 155 feet of colliding at nearly 33,000 miles per hour on Jan. 29, about 560 miles (900 km) above the Earth. While they passed each other safely, a crash would have generated a cloud of debris that could have threatened any spacecraft in orbit.

Two long-defunct US satellites came within 155 feet of colliding at nearly 33,000 miles per hour on Jan. 29, about 560 miles (900 km) above the Earth. While they passed each other safely, a crash would have generated a cloud of debris that could have threatened any spacecraft in orbit.

That’s why Planet, a leading remote-sensing satellite operator, is choosing to retire five of its satellites early this year. The company wants to make sure to meet a key safety standard adopted by industry and US regulators—that any non-functioning satellite de-orbit, that is, burn up in the atmosphere, within 25 years of ceasing operations.

If that sounds like a long time, consider that the two satellites that nearly crashed this week were launched in 1967 and 1983, and would have de-orbited a decade ago or more if they had followed similar specifications.

Today, satellite operators must obey a set of broad safety standards set by international law and their own domestic regulators; in the US, that’s the Federal Communications Commission. When most satellites were operated by the government or large companies closely tied to it, managing spacecraft was fairly easy.

But now private companies believe they can make big profits by flying satellites, creating a bloom of space traffic: From 2009 to 2018, 230 satellites launched every year. SpaceX added another 60 satellites to its Starlink constellation earlier this week. And market researchers at Euroconsult believe that 990 satellites will be launched annually in the next decade. That has regulators and companies alike scrambling to come up with new standards to ensure a safe operating environment, including even faster de-orbit schedules.

“The time to take action is before things are a crisis, not afterwards,” says Walter Scott, the CTO of satellite operator Maxar, who helped convene an industry group called the Space Safety Coalition. “As we look forward, we see a growing number of satellite constellations being planned, and the cost of access of space has come down where it’s even possible for elementary schools to put a little tiny cubesat in orbit.”

The set of satellites Planet is retiring is called RapidEye, one of the first commercially-built imaging satellite networks. The satellites, originally launched 2008 by the German firm RapidEye AG and later acquired by the Canadian company Blackbridge in 2011, were purchased by Planet in 2015 to complement its own Dove imaging satellites.

The RapidEye satellites were designed to operate for seven years, but they are still going strong more than a decade into life. They are being retired this year out of an abundance of caution.

“The system is actually still functional but as time goes by, the chances that something could happen become more and more significant. As a responsible operator, we felt like we had an obligation to make sure that the system will not contribute to the already critical situation of orbital debris,” explains Massimiliano Vitale, a senior vice president at Planet who has worked on the RapidEye satellites since 2006.

That effectively means lowering the altitude of the satellites from 640 km (398 miles) to about 590 km (367 miles), reducing de-orbit time from about 75 years to 25. The closer to Earth satellites are, the more they feel the effects of its atmosphere, which slows them down and allows gravity to pull them closer to Earth, where the atmospheric effects increase, and so on. Some new satellites are being built with “drag sails” to accelerate this process.

Decommissioned satellites also need to remove any onboard energy sources, a process called “passivation,” to prevent any future explosion. That includes exhausting any propellant, draining the batteries and permanently shutting off transmitters to prevent accidental radio interference in the future. “Essentially, it will be a cold piece of metal,” Vitale says.

Most satellites are designed to completely burn up as they descend through the atmosphere at high speed, but some larger vehicles, like space stations, survive re-entry. In that case, they are targeted to impact the planet in a remote section of the South Pacific affectionally called the spacecraft cemetery. Residents include the former Mir space station, numerous uncrewed supply spacecraft, and—almost—the first Chinese space station, Tiangong-1, which crashed into the Pacific a few thousand kilometers away from the aquatic boneyard.

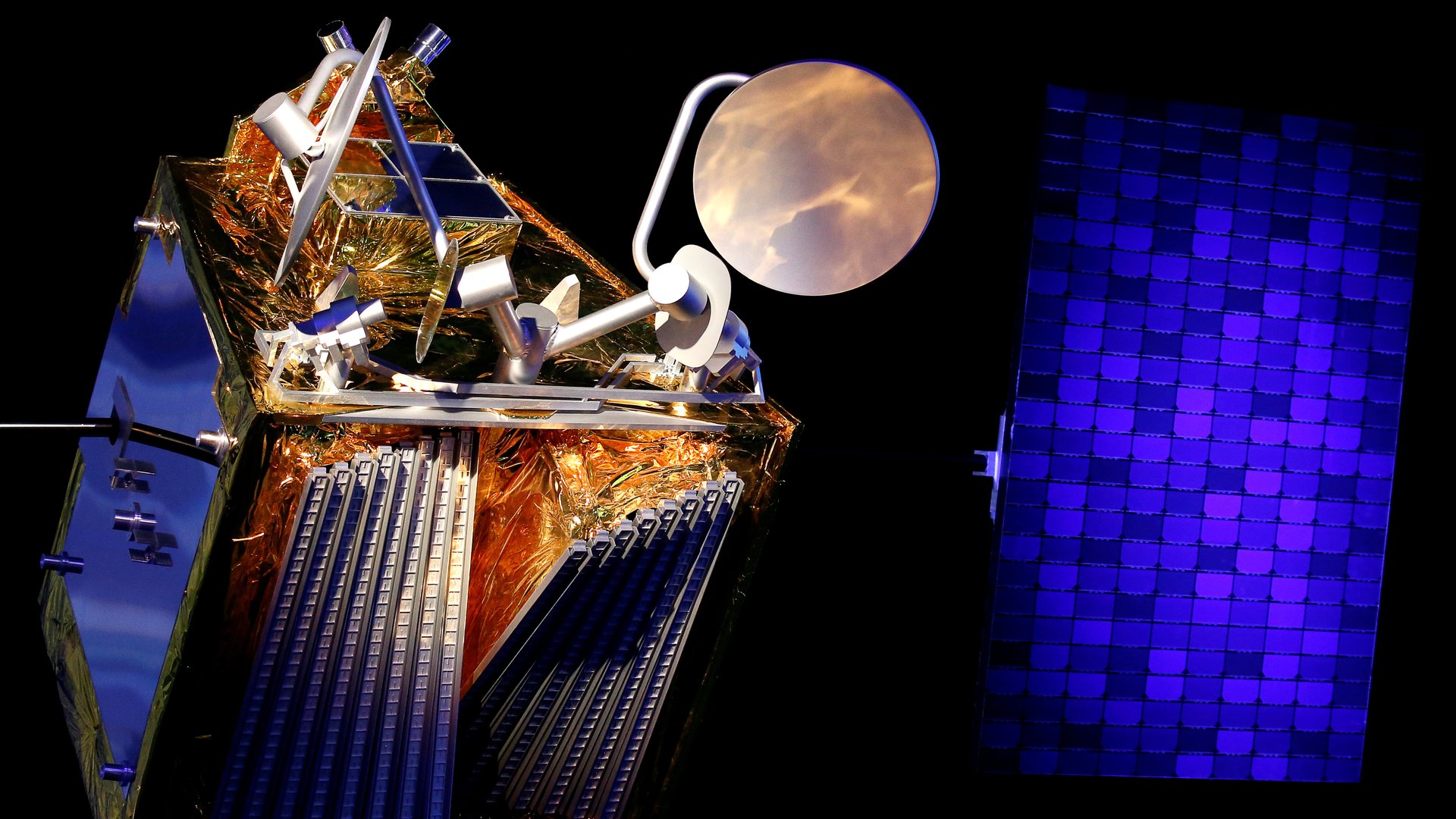

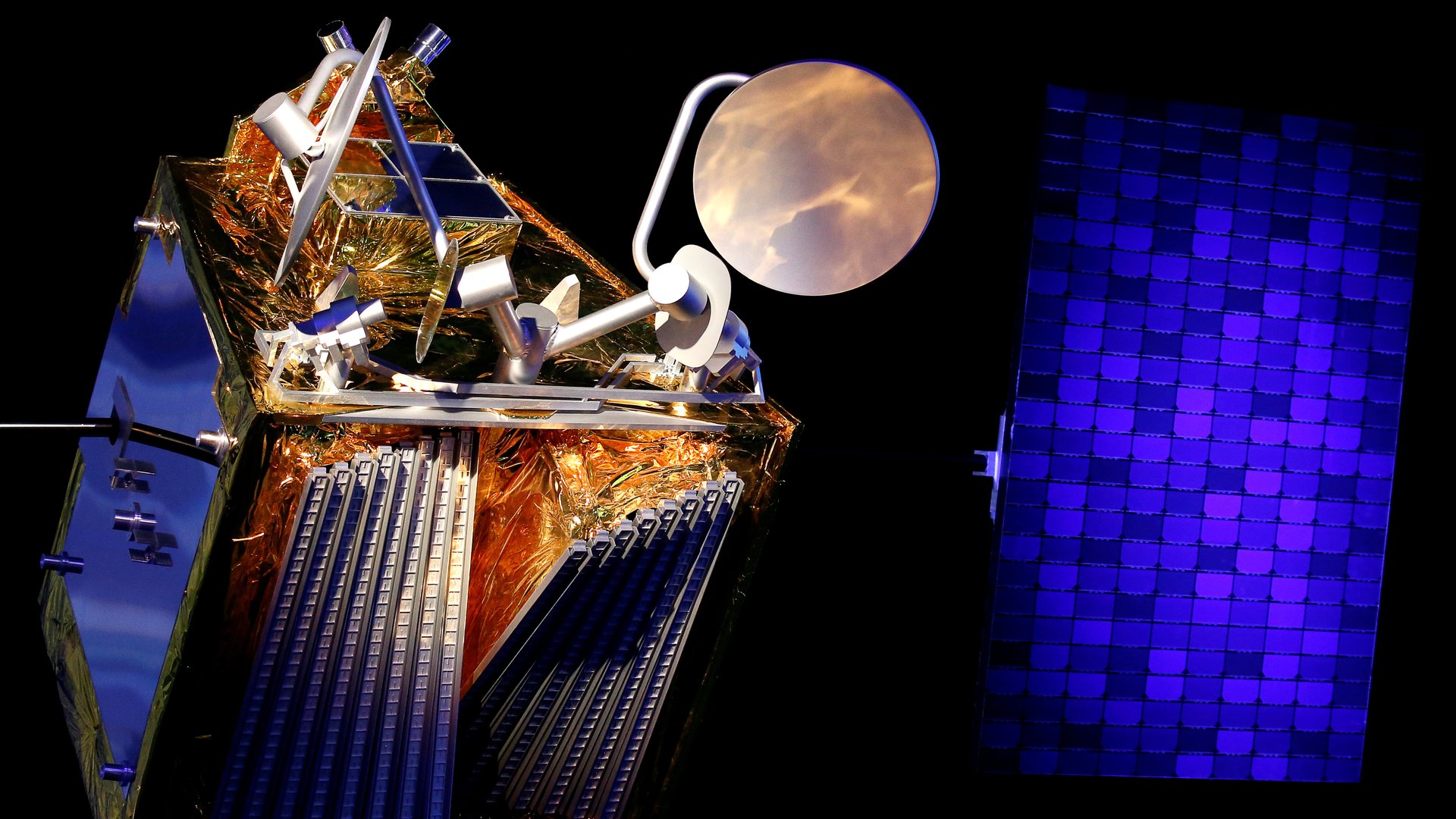

Some satellites are too far from Earth to be effectively de-orbited. In the case of geo-stationary satellites—which fly at high orbits about 36,000 km (22,236 miles) above the Earth, synchronizing their orbit with the rotation of the planet below—it would be impractical to fit them out with enough propellant to fly back down to the atmosphere when their operational lives are over. Instead, they are flown further up, to a graveyard orbit.

Even that isn’t always simple. DirecTV reported last week that one of its satellites, called Spaceway-1, suffered significant damage to its batteries that could cause the vehicle to explode if they are used. For now, Spaceway-1 is powered directly off its solar panels, but the company fears that when the satellite enters Earth’s shadow and must draw on battery power, it could be destroyed—and potentially endanger other satellites. DirecTV is seeking permission to fly the satellite to a graveyard orbit without removing all its propellant, as the best alternative to risking an explosion.

Avoiding such tricky choices is one reason why researchers and start-ups are also looking ahead to develop robotic spacecraft to service and re-fuel satellites for longer duration missions, or snag them and pull them down to a disposal orbit.