Uber’s new California commission caps only underscore the pricing opacity for drivers

In response to AB5, the new California labor law that makes it harder for employers to classify workers in the state as independent contractors, Uber in January capped its service fee on UberX rides in California at 25%. It was one of several changes ostensibly made to give drivers greater transparency, and a sense of autonomy meant to reinforce their non-employee status.

In response to AB5, the new California labor law that makes it harder for employers to classify workers in the state as independent contractors, Uber in January capped its service fee on UberX rides in California at 25%. It was one of several changes ostensibly made to give drivers greater transparency, and a sense of autonomy meant to reinforce their non-employee status.

The fee cap is part of how Uber tells drivers it wants to “make the fare structure more straightforward so it’s clear where your earnings and fees come from.” But there’s still a lot about Uber pricing that drivers can’t see.

Uber collects a “marketplace” fee, separate from the maximum 25% service fee, which means the total commission is a lot higher—some estimate the company’s “real commission” to be as high as 40%. And Uber has dropped this fee from its drivers’ receipts, meaning drivers have less-than-perfect insight into how much the ride-hailing giant is taking per ride.

Uber has been quietly raising its marketplace fee—now around $3 per ride in California—for years. It is a flat fee added to all of Uber’s economy car services (X, XL, Pool) to cover “operational costs.” It varies per ride and differs in each city.

“So you can imagine why they like raising that fee over time; they get 100% of the revenue from that,” says Harry Campbell, founder of the RideShare Guy blog.

The marketplace commission was first introduced in 2014 as a “safe ride fee” of $1 per ride to cover costs such as background checks for drivers and insurance and vehicle checks. But employees reportedly said the fee was never “earmarked specifically for safety,” and was instead devised to boost margins, according to an excerpt from New York Times reporter Mike Isaac’s book Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber. By the time the safe rides fee became fodder for a court battle in 2016, the company already had collected nearly $500 million in revenue from it. The case was settled for $27 million, and Uber changed the name from a “safe rides fee” to a “booking fee.” More recently, the name was updated to “marketplace fee.”

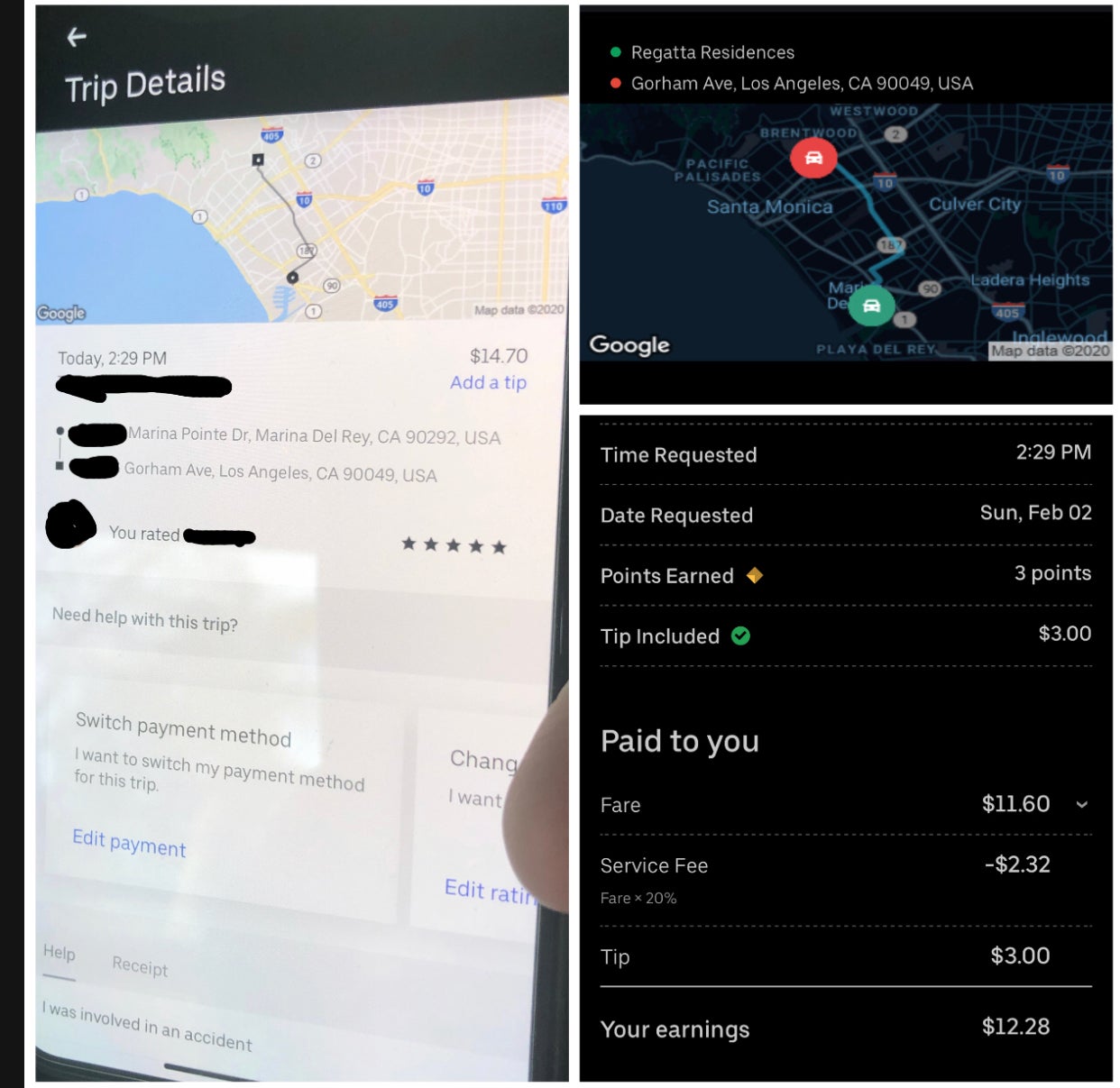

It’s not uncommon for drivers to compare the fares they see on their app with what their passengers are seeing, which would help them to detect any variations in fares. In a screenshot of a trip taken in January in Los Angeles, the total fare on the rider’s receipt (left) is $14.70 while the total fare of the driver’s receipt (right) is $11.60. The difference of $3.10 is the “marketplace fee.”

“If they were not hiding that, I would not be nearly as upset. If they were just honest about it, I would not care as much,” the driver who sent the screenshot wrote in an email to Quartz.

It’s hard to say whether the average driver is earning less than they believe they should be making. But the revenue line items on drivers’ receipts, which break down what’s being deducted, is one way to look into this.

Dropping the “marketplace fee” from driver’s receipts is a way for Uber to charge riders more without splitting it with the driver, says Campbell.

Uber says the fee still appears on drivers’ receipts outside of California. The change in California was made in response to AB5; in essence it helps clarify that Uber considers the fee information to be essential only to the rider and the company, and that drivers, as non-employees, are not part of that particular equation. (Rival Lyft, meanwhile, shows a breakdown of earnings on a weekly basis, which includes a “service expense,” the equivalent to Uber’s “marketplace fee.”)

None of this is to say that Uber hasn’t responded to some of the changes drivers have been wanting, such as being able to see where passengers are going and what the estimated earnings will be before agreeing to take them.

Each day, 14 million trips are completed on Uber. But the company is losing roughly $1 billion a quarter (save for a blip a couple of quarters ago, when it lost more than $5 billion). It needs to find ways to boost revenue. The booking fee, which goes straight to the company, is perhaps something Uber has been leaning on to help make up for the losses.

“I think if we look at sort of the history of the booking fee, that’s exactly what they’ve done,” says Campbell. “They’ve never done anything crazy [with it], but just over time they’ve slowly increased it, and obviously they have a lot of mandates to become profitable.”

Providing benefits like health insurance and minimum wage to California workers reclassified as employees under AB5 would be costly for the ride-hailing business, which is trying for—but has not yet succeeded in getting—an exemption from the new law. As a result, the changes Uber is making in response to AB5 to strengthen its stance on maintaining worker flexibility will likely continue.