Another 2020 election simulation ends in chaos

A group of people pretending to be anarchist hackers bent on disrupting the 2020 presidential election gathered early Friday morning in a nondescript hotel conference room in Manchester, New Hampshire. The town of 111,000 was quiet and cold. Blue Öyster Cult had played to a half-empty theater on Main Street the night before.

A group of people pretending to be anarchist hackers bent on disrupting the 2020 presidential election gathered early Friday morning in a nondescript hotel conference room in Manchester, New Hampshire. The town of 111,000 was quiet and cold. Blue Öyster Cult had played to a half-empty theater on Main Street the night before.

As the hackers plotted various strategies for swinging the results and sowing distrust in the nation’s voting process, a man in his late-30s sat at the head of the table, weighing in on each idea. They called themselves K-OS, for “Kill Organized Systems.”

The man, Yonatan Striem-Amit, was a former member of Unit 8200, the Israeli military’s elite cyber warfare team, which is considered among the best in the world.

A team of federal agents and members of local law enforcement were in a room right across the hall. No one had any idea what the hackers’ first move would be, and they knew anything was possible—except hacking into any voting machines themselves, because that wasn’t allowed under the rules to which both teams had agreed.

The election-hacking tabletop exercise, known as “Operation Blackout,” was not the first such Election Day 2020 “wargame” run by Striem-Amit’s Boston-based company, Cybereason. The objective of Cybereason’s public-private exercises, in light of recent election tampering successes by special interest groups and state actors, is for “law enforcement to learn what is possible during an election attack and giving them an opportunity to figure out ways of dealing with it,” Striem-Amit told the participants. In the scenario, the fictitious K-OS attempts to subvert the election by suppressing the vote in “Adversaria,” a fictitious medium-sized city in a fictitious swing state that could make the difference in who takes the presidency.

“This is not a creative storytelling exercise,” said a document distributed to participants beforehand. “The point of this event is to figure out how to better prepare for certain circumstances.”

There is “more infrastructure than you realize,” explained Streim-Amit. With a bar on attempting to manipulate actual vote tallies, K-OS would have to be creative in their targeting efforts, said Israel Barak, also a veteran of the Israeli Defense Forces cyberdefense wing. In a place like Adversaria, creating chaos and using disinformation to reduce turnout and suppress the vote, with a short- and long-term goal of undermining the public’s confidence in the US electoral system, could be enough to keep Adversarians away from the polls and potentially flip the state.

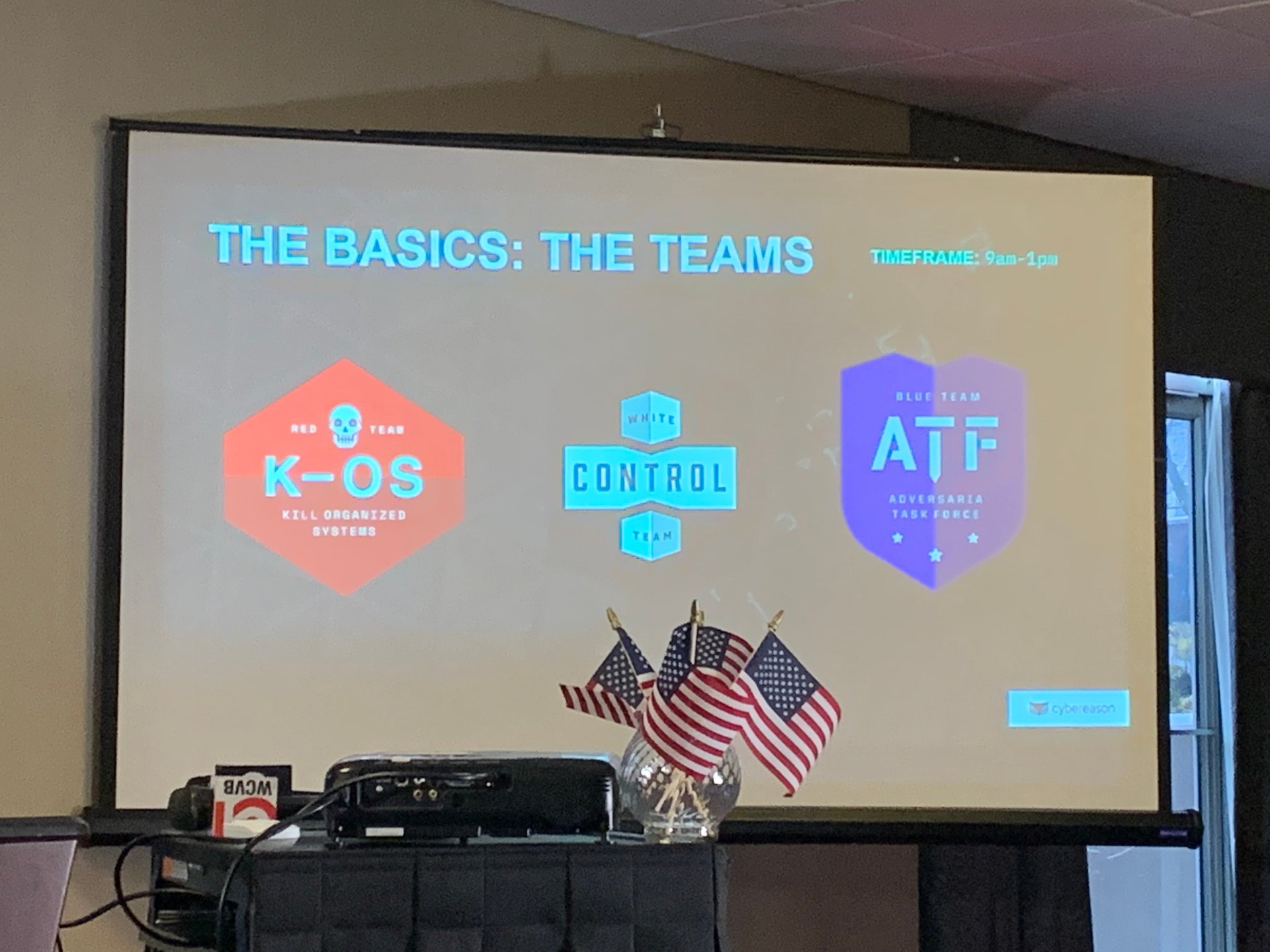

Like Cybereason’s last Operation Blackout simulation, which took place in November 2019, the Manchester simulation was set on November 3, 2020. Striem-Amit was overseeing the Red Team—K-OS—which was made up of other cybersecurity professionals and so-called white-hat hackers, as well as Ed Davis, the former Boston police commissioner. The Blue Team—the “good guys”—which included the US Secret Service, as well as officers and detectives from Manchester, Concord, and Nashua, New Hampshire, was charged with trying to stop them.

A White Team, consisting of third-party experts and observers, enforced the rules and decided the outcome.

With the Red Team unable to tamper with actual election equipment and change vote tallies, it forced them to consider how to swing the vote in other ways. The previous session ended with 32 dead and 200 injured, after the Red Team crashed autonomous buses into crowds of people in line at polling places. A few members of the Blue Team were attending for the second time, and said they found it somewhat unrealistic. This time, Red would be forbidden from pulling off the same sort of stunt.

Suppressing the vote by creating chaos

The Red Team began the day by hacking into and manipulating the Uber app, ginning up a steep spike in demand for cars. Uber accounts for about 10% of cars on the road in Adversaria, and the Red Team purposely sent drivers on suboptimal routes to tie up traffic. Red also used GPS spoofing to make Google Maps think there were more cars on the road than there were, in places they weren’t.

Next, Red spread a false rumor through local news stations that a major Democratic candidate had suffered a heart attack.

The Red Team now began seizing control of wireless networks, commandeering people’s cell phones, and generating social media reports of police stopping and frisking black men headed to the polls. The team then created additional fake news that undocumented residents were being targeted by ICE agents. Municipal social media accounts were also hacked, spreading disinformation from official sources.

At this point, Red took over the city’s traffic lights, bringing cars in three voting districts to a standstill. The Blue Team deployed police officers to affected intersections, directing traffic the old-fashioned way while maintenance crews tried to get the lights working again.

Turnout at the polls began to suffer slightly as people started staying away from voting sites. Some didn’t want to deal with the heavy traffic. Others were wary of being stopped and frisked by police, not realizing the reports were false.

City officials announced to the public that there were hacks in progress and that cell networks had been compromised. They got confirmation from the “sick” Democrat’s campaign that everything was actually okay, and broadcast this fact out to the populace.

The Red Team, which spent part of the morning creating deepfake personas, now began to overwhelm the 911 system with false alarms for fires, medical calls, and other tasks to waste first responders’ time. The police and fire departments couldn’t distinguish between real emergencies and fake ones—and are legally bound to respond to every call that comes in.

They ramped up the pressure in stages, eventually putting serious stress on public safety resources by reporting nonexistent bomb threats and active shooters at schools in Democratic districts over the city’s emergency broadcast system—something Red gained control over when they hacked the area’s wireless networks. Blue told people to shelter in place at home and that a manhunt was underway near polling places.

Cops were soon stretched paper-thin, and a number of reserves were activated. The Blue Team activated the 911 system’s GPS locator, and started to deprioritize phony calls.

The Red Team then began discussing ways of weaponizing Adversaria’s sewage system. It would take a little while to figure out how to get access to the controls, but Red had now gained block-level control over the local electrical grid.

They decided to burn out the system with coordinated power surges, hitting fire stations, campaign HQs, radio towers, hospitals, and the mayor’s office. The city’s subway system ground to a halt, and the Fire Department began responding to the tunnels to rescue stranded passengers.

“There’s not a door you can knock down to stop this,” remarked one of the police officers participating.

The Red Team spared Adversaria’s cell towers, in order to maintain their ability to spread fake news. And since hacking the machines was expressly prohibited, it was time to give Adversaria’s voters another reason to stay away from the polls.

In what they hoped would be their master stroke, Striem-Amit and the others took control of the city’s sewer system and concocted a plan to create massive citywide backups that would fill the streets and people’s homes with excrement. However, the plan was foiled not by authorities but by their earlier takedown of the electrical grid—without power, Adversaria’s sewage pumps were dead.

The debrief

Ultimately, the widespread power outages and concerns about cyber intrusions led authorities to suspend the election. It was rescheduled for a week later, and although the election would still happen, public trust in the broader electoral system suffered.

By keeping people safe and avoiding catastrophe, Cybereason’s Dani Wood, a Blue Team facilitator, said the Blue Team’s showing was “largely a win.”

“It’s not [the police department’s] job to make sure the election goes smoothly,” said Wood.

In the made-up town of Adversaria, “Uncertainty still exists about the legitimacy of the election,” said Striem-Amit, “so even though safety was achieved, the long-term goal of the attackers was still advanced.”

Striem-Amit estimated the hackers’ total cost would have been between $1 million and $3 million—mostly to pay for so-called “zero day” exploits for hacking into phones and control systems. “None of the techniques we deployed today is science fiction,” he said.

The challenge for police departments across the nation now is to continue to broaden their knowledge about what kinds of infrastructure attacks are possible.

However, said Wood, “We knew we were participating in a game, [but] in the real world we don’t know what’s happening…and who is doing it.”